Corporate Watch

By Amelia H. C. Ylagan

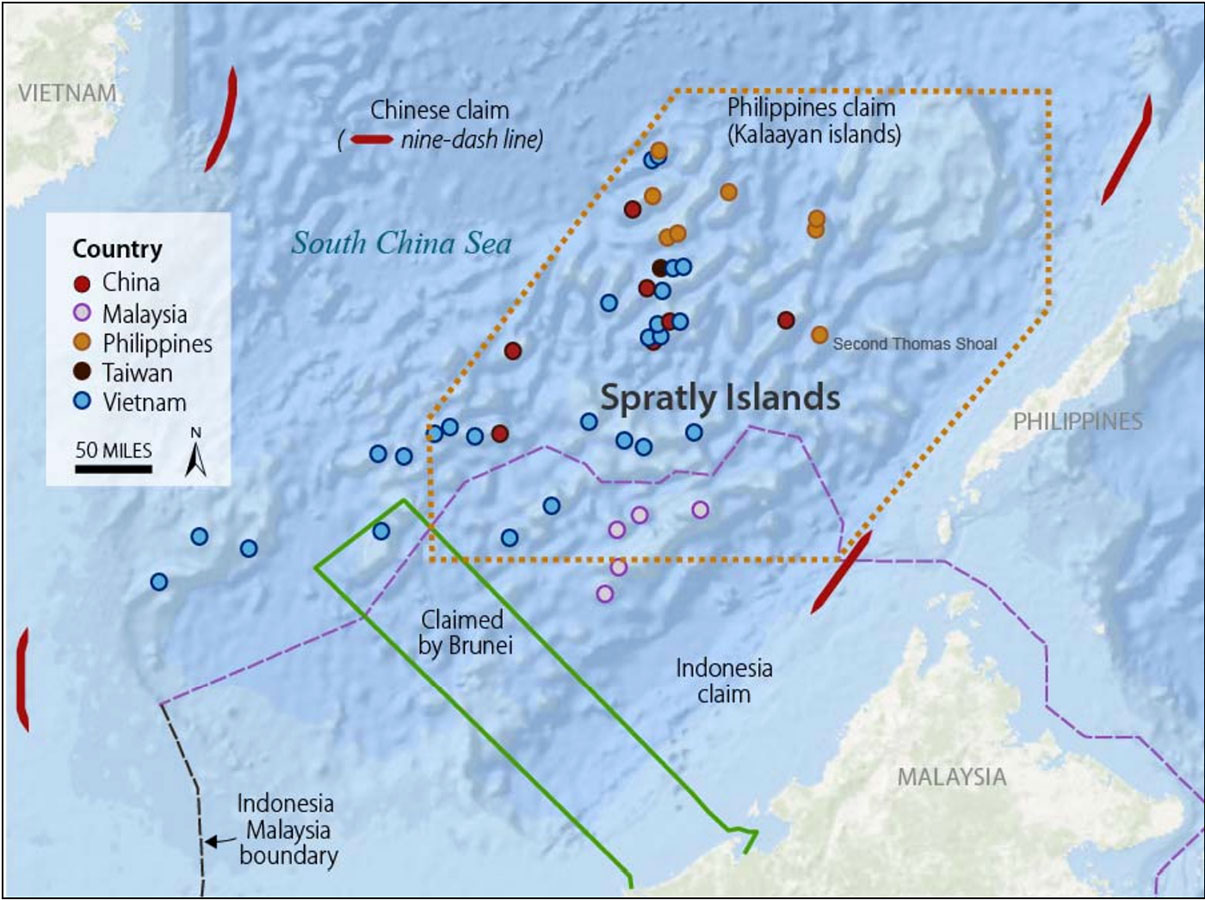

China’s insistence on its own “nine-dash line” as its demarcation of its territorial and sovereign rights in the South China Sea has caused conflicts of interest with and among its neighbors. Its self-serving boundaries cover most of the South China Sea (SCS), overlapping with the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) claims of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam.

What is mine is mine. What is yours is mine, China says.

This was heightened since 1982, when the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) determined the very specific 200-nautical miles EEZ for each country. Article 56 of UNCLOS affirmed that coastal states have the right to the exploration and management of all resources within their EEZ. Southeast Asian countries’ EEZ stress the geographical fact that their coastlines are really much closer to the disputed areas than China’s is, UNCLOS said.

Still, nearly the whole South China Sea is claimed by China with its nine-dash line. This line cuts into half of the Philippine’s EEZ.

Filipino ships and small fishing boats have been repeatedly attacked by Chinese patrol boats in the Philippine EEZ. On Sept. 5, 2012, Philippine President Benigno Simeon Aquino III promulgated Administrative Order No. 29, naming the maritime areas on the western side of the Philippine archipelago as the West Philippine Sea (WPS), and defining “sovereign jurisdiction” in its EEZ. China ignored this, controlling fishing, reclaiming land and building military outposts in the WPS.

On Jan. 22, 2013, the Philippines instituted arbitral proceedings against China in a dispute concerning their respective “maritime entitlements” and the legality of Chinese activities in the South China Sea. On Feb. 19, 2013, China expressed its rejection of the arbitration in a diplomatic note to the Philippines.

On July 12, 2016, the Arbitral Tribunal in the South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China) issued a unanimous award largely favorable to the Philippines. China’s nine-dash line is invalidated by the 200-nautical mile EEZ of countries in the South China Sea. Scarborough Shoal and rocks like Spratly Islands that cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own and accordingly shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf (and are therefore under Philippine control). There is no possible entitlement by China to any maritime zone in the area of either Mischief Reef or Second Thomas Shoal and these are within the Philippine EEZ.

China has rejected the arbitral ruling. And China continues to act like “What is yours is mine.”

International law experts worry that “There is no enforcement mechanism as such under UNCLOS in the event that China fails to comply with the tribunal’s decision, but the Philippines could either resort to diplomatic ways (bilateral or multilateral negotiations within the framework of international organizations) or have recourse to further arbitration under UNCLOS. Moreover, other states and non-state actors could take further actions (i.e., economic sanctions) to put pressure on Beijing to shift its behavior” (Department of International Law, The Graduate Institute, Geneva).

But perhaps the more defeating quirk of fate is that the Arbitral ruling came out in July 2016, when national elections had just installed the new president of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte. He and Chinese president Xi Jinping created the biannual Bilateral Consultation Mechanism on the South China Sea, a process allowing the two nations to peacefully manage disputes and strengthen their relations. Wasn’t that a good thing for Philippine-Chinese relations?

It could have been. But China did not lay off its coveted areas in the West Philippine Sea.

In March 2017, China occupied Benham Rise, a protected food supply exclusive zone of the Philippines (to the east of the country), on the pretext of “oceanic research,” claimed to be approved by Duterte (Asia Times, Archived from the original on May 6, 2024). Speculations were that China was aiming for naming rights for Benham Rise, which was hurriedly countered by it being renamed “Philippine Rise.”

In June 2019, a Chinese ship, Yuemaobinyu 42212, rammed and sank a Philippine fishing vessel, F/B Gem-Ver, near Reed Bank, west of Palawan. The fishermen were caught by surprise as they were asleep during the event. The Chinese ship afterwards left the sinking Philippine vessel, leaving the 22 Filipino fishermen adrift in the middle of the sea. They were later rescued by a ship from Vietnam (ABS-CBN News, April 14, 2020).

Concerned Filipinos sank to a sickening distress when, just before he stepped down as president at the end of his term, Rodrigo Duterte said that the victory of the Philippines over China at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague is just a “piece of paper, trash to be thrown away” (Inquirer.net, May 6, 2021). And it seemed that China had paraphrased itself with its mantra, “What is yours is mine” — in Duterte’s betrayal of patriotic loyalty.

The election of Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr. as president of the Philippines in 2022 saw the onset of worsening Philippine-China relations and frequent skirmishes in the South China Sea.

Among the escalations seen in the news since 2023 include the China Coast Guard’s firing on Philippine military ships in the Spratly Islands waters; the Philippines accusing China of parking its navy and coast guard vessels near Scarborough Shoal in an apparent attempt to block Philippine vessels from passing through the area; the Philippine Coast Guard accusing China Coast Guard ships of jamming their automatic identification system (AIS); and, amidst Chinese and Philippine military operations around the disputed Scarborough Shoal in August 2024, the Armed Forces of the Philippines accusing China of “dangerous and provocative actions” after two Chinese Air Force aircraft dropped flares in the path of a Philippine plane that China claimed was “illegally intruding” into its airspace.

Additionally, in May 2024, the Philippines’ Department of Foreign Affairs said it would probe Chinese diplomats’ activities around wiretapping after reports surfaced of a recording of an agreement between a Philippine military official and Chinese officials over the South China Sea.

A week ago, China and the Philippines accused each other of causing a collision between their two vessels in the latest flareup of tensions over disputed waters and maritime features in the South China Sea. It was the second confrontation in days near Sabina Shoal, about 140 kilometers (85 miles) west of the Philippine province of Palawan, in the internationally recognized EEZ of the Philippines (Associated Press, Aug. 31, 2024). The ramming by the Chinese vessel damaged the 97-meter (320-foot) Teresa Magbanua, one of the Philippines’ largest coast guard cutters (Reuters, Aug. 31, 2024).

But didn’t former president Duterte admit to have had a (verbal) “secret agreement” with Chinese President Xi Jin Ping to “maintain the status quo” in the West Philippine Sea? Duterte’s former spokesman Harry Roque recently divulged the status quo deal, which he also called a “gentleman’s agreement.” He made the statement following a series of acts of Chinese aggression against Philippine vessels on resupply missions to the BRP Sierra Madre (ANC News, April 12, 2024).

Duterte said the secret deal involved not bringing construction materials for the repair and upkeep of BRP Sierra Madre in Ayungin Shoal. “As is where is nga. You cannot bring in materials to repair and improve the ship. If you rile China, there may be war.” Duterte challenged his successor, President Marcos Jr., to repair the BRP Sierra Madre that was deliberately grounded by the Philippine Coast Guard on Ayungin Shoal to establish Philippine ownership (ABS-CBN News, April 12, 2024).

What is mine is mine, the Philippines says.

What is yours is mine, China says.

Amelia H. C. Ylagan is a doctor of Business Administration from the University of the Philippines.