GeoLogics

By Marian Pastor Roces

The symbolic American “street” — the National Mall in Washington, DC, flanked by the Smithsonian Institution museums on the longitudinal sides and on opposite ends, by the Washington Monument and the US Congress building — has literally embodied mass protest in 20th century America.

From even before the 1963 Civil Rights Movement protests (the occasion for Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” address) to the war protests against the 1970’s American military action in Vietnam and Cambodia, to the demands for women’s and gay rights, the National Mall’s kilometer long stretch emerged as hallowed ground.

“America’s Civic Stage” for contesting the status quo — for proposing alternative, libertarian narratives and action — was the end point of the “The Longest Walk” from Alcatraz in San Francisco, to bring attention to the rights of Native Americans.

Paris’ Place de la République is its “street” for both mass protest and collective mourning. Actually a 3.4-hectare square (the intersection of several arrondissements), the space saw 1.6 million people congregate around its Monument à la République in 2016, in collective outrage over the terrorist attacks on their city.

This biggest demonstration in French history is only one of the habitual uses of this special place, towered over by the 1883 Monument à la République — reverentially called the Marianne, a symbol of France. Marianne holds a representation of the Déclaration des droits de l’Homme et du citoyen de 1789 (the Declaration of Rights of Man and of the Citizen).

The 23-meter-high monument of Marianne was installed to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the French Revolution. It calls to mind the rootedness of modern democracy — including the United States liberal version, called Jeffersonian democracy after its paradoxically slave-owning writer — in the universality of the principle of human rights. Hence in the 18th century French Revolution.

OLD SQUARES, RENEWED MEANINGS

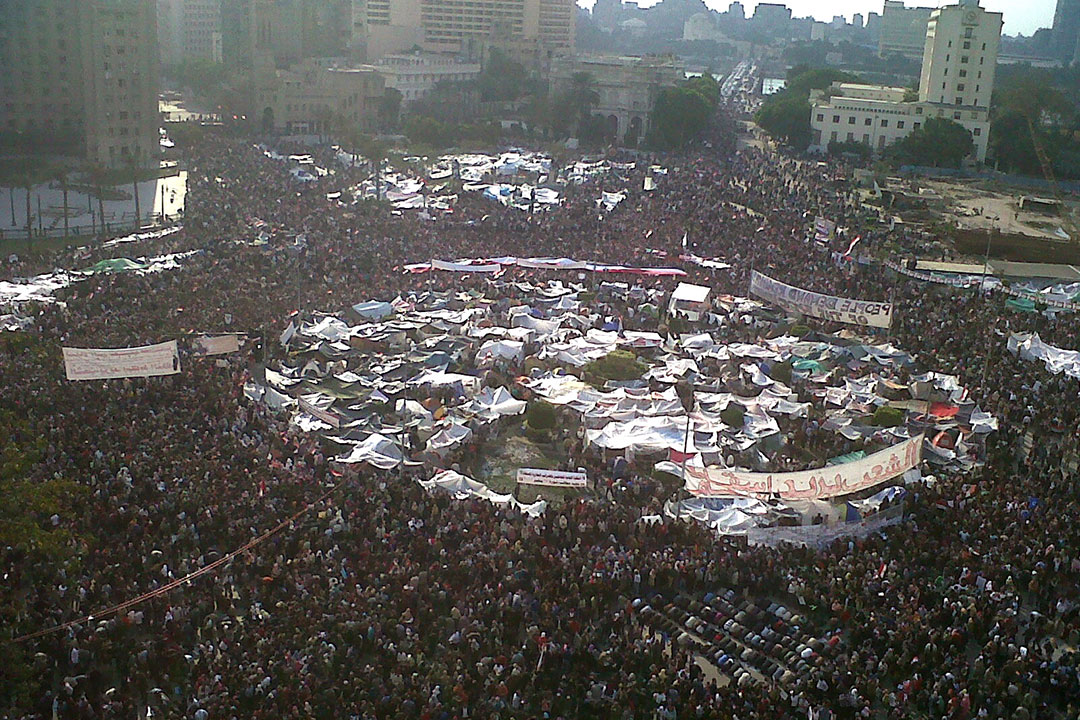

Of more recent vintage as a site of protest is the rather old Tahrir Square of Cairo. This space was already symbolic before the 2011 eruption of the Arab Spring in North Africa. “Tahrir” is liberation in Egyptian. It was the name given this round-rather-than-square intersection point in the Cairo downtown area, which was originally called Ismailia Square after Khediv Ismailia, the Egyptian founding father.

Marking pivotal moments — the Egyptian Revolution of 1919 and that of 1953, which changed Egypt from a constitutional monarchy to a republic — the Tahrir name stuck. Major protests gravitated towards it: the 1977 Bread Riots, for example, and the 2003 protests against the war in Iraq.

And in 2011–2013, it was to be the focal point of enormous protests against the inability of President Hosni Mubarak to deliver the promise of democracy; and subsequently, a counter-revolution against President Mohamad Morsi (who was killed, following passions against the super-conservative Muslim Brotherhood), leading to the ascendance of the present leader, Abdul Fatah al-Sisi.

Tahrir Square, an old space imbued with new political purging/renewal meanings, is curiously analogous to a rather small space in a nearby country — Spain. It is the space of performance for the flamenco.

Written for the site 1Win-ES.pro this year: “Flamenco was born in the courtyards, caves and streets of southern Spain, forged in the oppression of the Gitanos (Roma), the anguish of Sephardic Jews and the sorrow of displaced Moors. It was — and remains — the soundtrack of exile.” Born in pain, its performance is always an act of resistance.

There are myriad flamenco performance spaces in Spain’s cities, particularly in Andaluz. For centuries, the extraordinary dance/song form voiced resistance to the Spanish status quo, even during the dictatorship of Generalissimo Franco, who sought to co-opt this form of the marginalized by gentrifying it and remaking it as a tourism come-on.

But this recent BBC News report intrigues “…the flashmob group Flo6x8 has rebranded flamenco as a powerful political weapon. This anti-capitalist group has been well publicized for its political performances that have taken place in banks and even the Andalusian Parliament. Using the body and voice as political tools, the group carries out carefully choreographed acciones (actions) in front of bemused bank staff and customers. These performances are recorded and then posted online, attracting a huge number of views.”

HECTARAGE FOR MILLIONS

The Philippines’ National Capital Region has two spaces for venting collective outrage, also driven by the aspiration for sociopolitical reform. One of these spaces is the 58-hectare Luneta Park, which is just outside Fort Santiago, the Spanish soldiers’ barracks, at the mouth of the Pasig River facing Manila Bay. The space is at least half a millennium old.

The park called Bagumbayan (New Town) until the late 19th century is invested with powerful cultural energy from having been the place of execution of Jose Rizal. Reconstrued as a lunette-shaped space in the early 20th century urban plan of the American Daniel Burnham, it became Manila’s official ceremonial space: presidential inaugurations, Independence Day parades and the like are regularly staged here.

So, too, are rallies planned to bring in millions of people. The scale of Luneta accommodates this many Filipinos wanting public venting of collective fury. But so can a narrower space, the EDSA People Power site at the corner of Ortigas Avenue. The place where millions demanded the ouster of the authoritarian Ferdinand E. Marcos has been made narrow by an overpass.

On Nov. 30, both sites will have received millions of Filipinos, ideologically divided according to site, but commonly enraged by the nearly unthinkable scale of corruption in government. Manila’s protest spaces are much bigger now than the pre-WW2 Plaza Miranda fronting the Church of Quiapo, which was the reference for the confronting question asked of would-be political advocates: can you defend it in Plaza Miranda?

It’s a reminder that cities that allow alternative flows of history can manage to give democracy a chance. Chances, really. Democracy’s promise is nearly always clipped, sometimes in the bud. But so long as there is that hallowed ground, hallowed ideals might survive.

Alternatively, see what happened after the events of June 4, 1989, at Tiananmen Square — a complete erasure.

Marian Pastor Roces is an independent curator and critic of institutions. Her body of work addresses the intersection of culture and politics.