Is it time for an agriculture rebound under Secretary William DAR’s leadership?

Many were surprised when in the second quarter of this year the agriculture sector outpaced industry and services. GDP declined year on year by 16.3% in real terms. Industry and services tanked, having contracted by at least 15.7%. But not the farming and fisheries sector, which posted the lone positive growth of 1.5%. For at least the first half of this year, agriculture’s performance provided the silver lining for the Philippine economy in the months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The unexpected development is easy to explain, the result of exempting the sector from the stranglehold of a COVID-19 economic lockdown. From this likely one-off performance emerges a view that the sector can at least do better than its performance over nearly half a century has been. Agriculture growth has been slowest and contributed the least to the country’s GDP. The sector contributes only about a fifth of the growth of the country’s GDP in a normal year, in contrast to industry and services, which on average over the last six years have pulled up overall economic growth. In 2018, while the GDP grew by 6.2%, that of agriculture and fishing registered 0.8%.

The dismal economic performance of the sector is reflected the sector’s declining farm productivity and its shrinking tradability.

Falling farm yields. With few exceptions, farm yield growth rates of over 20 crops and two aquaculture products have generally been low or declining in recent years. Rice, the country’s largest crop, had a compounded annual productivity growth rate (CAGR) of -0.15% from 2014 to 2018. In contrast, that of corn farming, two-thirds of which involves planting genetically modified hybrid yellow corn used in animal feeds had a positive albeit insignificant growth at 0.79%. (See Chart 1.)

IFPRI in 2018 compared our sector’s land and total factor productivity indices with our ASEAN neighbors and we have a lot to catching up to do.

The land productivity estimates of selected ASEAN countries in 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2014 did rise for all countries. But the Philippines, which started out in 1990 with the second highest index after Vietnam, lost this advantage to all except Indonesia and Thailand. Our land productivity growth was the slowest. (See Chart 2.)

The total factor productivity (TFP) growth for the same countries and period shows that we had higher growth than Malaysia and Vietnam in the 1990s. TFP growth then decelerated for all, except for Thailand and Vietnam and with our TFP experiencing the slowest growth. In the last period, 2010-2014, TFP of the sector contracted. (See Chart 3.)

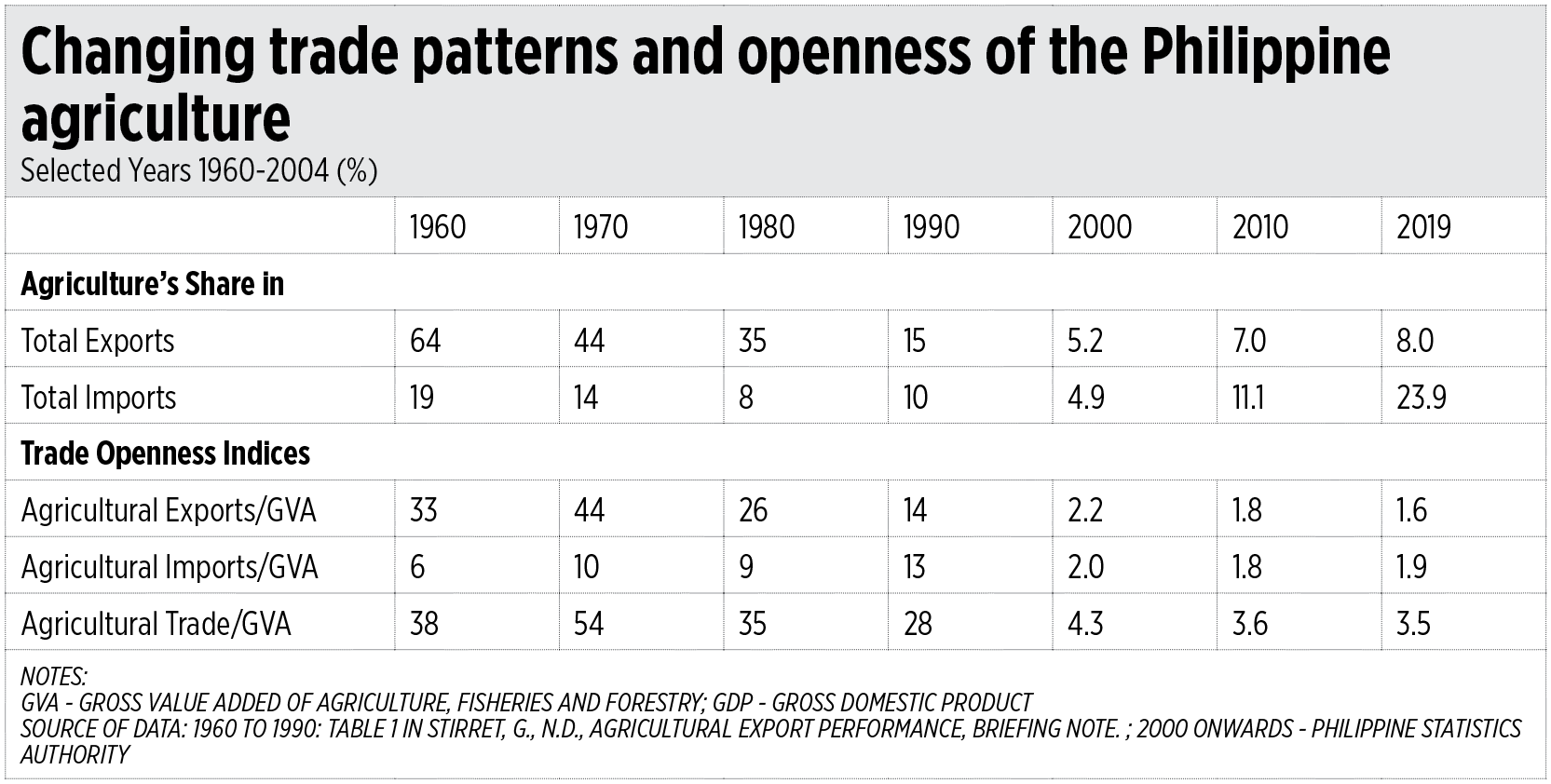

Shrinking tradability of the sector. The capability of the sector to engage in international trade has deteriorated significantly. In 1960, agriculture accounted for 60% of the total exports of the country. Sixty years later, the figure went down to 8%. Agricultural imports were 19% of the total in 1960 and increased to 24% in 2019. Import substituting industries in agriculture turned out not to be competitive enough so that when trade protection of them was lowered in compliance with the country’s obligations in the WTO Agreement on Agriculture, food imports, particularly rice, increased.

Trade openness indices show a pattern of shrinking tradability of the sector and a reduced capacity to trade internationally. In 1960, a third of the value added from agriculture were exported. That number dropped to only 1.6% in 2019.

Despite their rising share in the country’s total imports, imported agricultural products ended after 60 years with having a share of only 1.9% of gross value added (GVA), a third of what they used to have in 1960. The total tradability part of the sector plunged from 38% in 1960 to only 3.5% in 2019.

Agriculture Secretary William D. Dar took the helm of the Department at a unique and opportune time. He started his term with rice policy-induced inflation, which we solved by letting go of the National Food Authority (NFA). He fought his first major policy battle on rice tariffication and decided to take the less traveled road of supporting the Rice Tariffication Law (RTL). It was a bold step, abandoning the tradition of costly rice self-sufficiency programs and NFA rice import monopoly. (See the Table.)

However, he continues to face the pressure of showing that letting go of import restrictions in rice is good for the sector. He needs to put in place complementary programs to import liberalization to increase rice farm productivity and incomes of rice farmers. As it is right now, import liberalization, which pushes rice prices down, is creating new friction on the farming side of the industry, feeding the embers of the opposition to RTL.

Secretary Dar has the Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF) to use in his effort to deliver a new rice industry of the country. The fund is rigidly designed by law, but nonetheless he is sitting on at least a P10-billion fund yearly.

Akin to that momentous decision he had to take of supporting the RTL, he is now called upon to effectively convert the RCEF into higher rice productivity even as the industry is opened up to import competition.

Past administrations had simply poured money into the rice industry to demonstrate they had used the resources for their intended use. Their investments boiled away into thin air, leaving white elephant infrastructure facilities as proof that budgets were used, but farmers remained poor.

Repeating the way his predecessors spent public resources for the rice industry would likely create the same legacy for his administration, and, down the road, raise the likelihood of a failed experiment in liberalizing rice import policies.

What road less traveled in public spending in the rice industry should he take this time?

Ramon L. Clarete is a professor at the University of the Philippines School of Economics.