In defense of the Holy Fiscal Deficit: Accounting and economics

Part I: The dislike for fiscal deficits and the reality of their role in the economy

Part I: The dislike for fiscal deficits and the reality of their role in the economy

By Jesus Felipe and Mariel Monice Sauler

THERE APPEARS to be a broad consensus across the different sectors of our society that fiscal deficits are to be avoided. The rationale is that a government cannot spend more than it collects in taxes, certainly not routinely. With some nuances, the business community, government officials, academics, bankers, journalists, and the average person on the street, are aligned in thinking that a fiscal deficit damages the economy. We need to be fiscally responsible, like a good family. Fiscal deficits bring back memories of the 1980s, today even more so in the face of the corruption scandal. On top of this, we have been influenced by the IMF and the World Bank’s policies and way of thinking.

In this three-part series, we will argue that this widespread understanding of fiscal deficits is incorrect. Underlying it are three fundamental errors — deeply entrenched beliefs. One is that the finances of the nation are like those of a family or a firm. Second, that the money that the government uses to make payments is taxes. Indeed, society at large believes that taxes finance spending, in the sense that the government needs to collect taxes prior to spending, and that taxes are used by the central government to spend. And third, that pesos are a resource, something scarce like oil. All three are incorrect, and do not correspond to the reality of government spending and taxation in a modern economy.

In what follows, we elaborate upon a series of arguments, based on facts, that explain what a fiscal deficit is and its role in the economy, and argue that apprehensions about it are, in most cases, groundless. We hope the article contributes to dispelling this widespread belief.

Before we proceed, we stress that it is obvious that government spending has to be judicious and that corruption has to be eradicated. But it is important to understand that running a fiscal deficit is not tantamount to being corrupt or inefficient. Our government might be criticized but not because it runs a deficit.

Let us start with the simple fact, missed by most people, that a government (fiscal) deficit means that the government spent more on services for all of us than it collected in taxes from us. If the government runs a deficit, the private sector must run, on aggregate, a surplus. Naturally, it matters what the government spent on but that is a different issue, however important. This point is crucial so let us stress it: a fiscal (government) deficit occurs when the difference between what the government collects in taxes and what it spends as summarized in the national budget (roads, bridges, schools, hospitals, etc.), is negative. To make this crystal clear, it means that the private sector receives more from the government in terms of infrastructure payments (a company that was awarded a contract to build a road or a school; civil servant salaries) than it pays in taxes. A fiscal deficit increases the net worth, that is, saving, of the private sector. Complain about this? Want to reverse it? It is ironic that the business community does not seem to grasp what a fiscal surplus would do to the private sector, namely, we would pay more in taxes than the government would spend on services. Is this what they advocate?

Looking at the government’s fiscal position in isolation is bad economics. The reason is that there is a crucial connection between the fiscal position (Taxes minus Government Spending, let’s call this difference A) and the other two key sectoral balances of the economy: that of the domestic private sector (Private Saving minus Investment, let’s call this difference B,) and the current account (the foreign sector, essentially exports minus imports, let’s call it C). The three sectoral balances add up to zero by construction as follows: A + B – C = 0 (with these signs). It is the result of how the national accounts are built. This is the same in every country and it has to be so for good economic reasons. Not understanding the economics that underlies the link among the sectoral balances leads to erroneous statements.

As noted above, the three sectoral balances, government, domestic private sector, and foreign sector, add up to zero by construction. This means that if the government runs a deficit of, for example, 5% of GDP (A = -5%), the private sector (jointly domestic and foreign sectors) must run a surplus of 5% of GDP (B – C = +5%). Likewise, if the government runs a surplus of 5% (A = +5%), you can be certain that the private sector will run a deficit of 5% of GDP (B – C = -5%). This is not a theory. It is factual.

We hope the reader starts thinking about what this means and why looking at the fiscal deficit in isolation is dangerous. Let’s put all this in the context of the Philippines economy. We know that in all countries, the domestic private sector prefers to run a surplus (for example, B = +5%). This means that the fiscal balance and the foreign sector must run, together, a deficit of the same size (A – C = -5%). Now consider the following fact. Most of the time the Philippines runs current account deficits (C is negative). The algebra of the sectoral balances tells us that for the domestic private sector to be able to run a surplus (B positive), in the face of a current account deficit, the government has to run a fiscal deficit (A must be negative). There is no other way. This is neither good nor bad but the reality. We are not an exporting nation hence the current account deficit. Moreover, we also know that domestic private sector deficits are a good predictor of crises. If we want to prevent a crisis like the one in 2008-09 in the West (caused by large domestic private sector deficits during the years before), we need to ensure that the government provides the domestic private sector the funds to run a surplus. It is the fiscal deficit what brings macroeconomic stability to our economy.

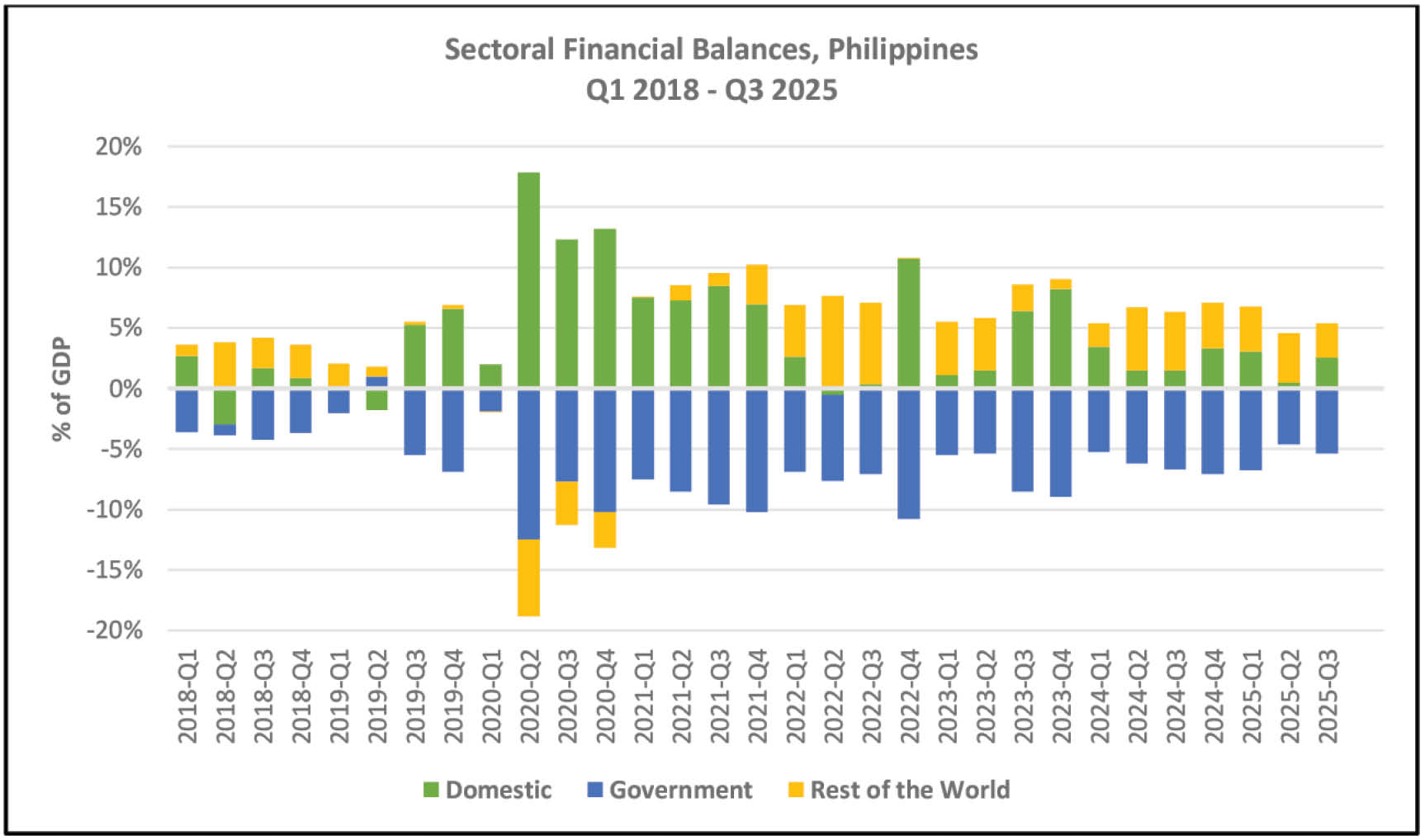

The sectoral balances figure (shown as percent of GDP) documents these arguments. The three bars (sectoral balances) add up to zero, by construction, for each quarter. In most quarters, the Philippines runs a current account deficit (bars above zero in the graph), a fiscal deficit, and a domestic private sector surplus.

Notice the quarters in 2020: large domestic private sector surpluses that mirror large fiscal deficits (up to 10% of GDP). Government deficit hawks do not understand this. Actually, it is the economies with a private sector in deficit the ones that run into crises, as happened just prior to the 2008-09 global financial crisis, not economies with budget deficits above 3%. It was a lack of understanding of private debt that led the entire profession of neoclassical economists to famously miss the build-up of the largest household debt bubble of all time in the 2000s, while simultaneously labeling the period as “the Great Moderation.”

What is difficult to comprehend is that government officials do not seem to understand the economics of the sectoral balances either, and they aim at reducing the fiscal deficit to A = -3% of GDP by the end of the administration, as if it was a great objective and achievement. They think that this helps the economy. This is a self-imposed constraint that reduces the sustainable policy space of the nation. The reason is simple: this forces the overall private sector (B – C) to run a surplus of 3% of GDP. Suppose we run a current account deficit of C = -4%. This implies that the domestic private sector will run a deficit of B = -1% of GDP. We insist that if with the economy that we have, including the current account deficit, the government does not run a deficit, we’d better start reciting all our prayers. The economy would enter a depression.

On the other hand, if we do not want the government to run a fiscal deficit, while maintaining the private sector surplus, we need to change the economy and be able to run a current account surplus (C positive), that is, we need to become Germany, Singapore, or Japan at some point in their history, and have their manufacturing-exporting companies. The current account surplus is the injection into the economy. They do not need another one. In fact, they need to avoid it if such a surplus is large, in which case they have to run a fiscal surplus. Changing the structure of the economy requires an industrial policy, a topic that we leave for another article.

The solution to the corruption scandal is not to kill the fiscal deficit. We would need it with and without corruption. The solution is to improve governance and punish the culprits.

(To be continued.)

Jesus Felipe is a distinguished professor and research fellow at the Carlos L. Tiu School of Economics, De La Salle University. Mariel Monice Sauler is an associate professor and chair of the Carlos L. Tiu School of Economics, De La Salle University. The authors are grateful to Eunice Gerenia, economics student, De La Salle University, for her excellent research assistance.