Signs And Wonders

By Diwa C. Guinigundo

While Vice-President Leni Robredo was considered by Nomura Global Research as the market-friendly choice as the next president of the Republic, former Senator Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. was dismissed as an uncertain choice. Nomura believed that Marcos Jr. is less market-friendly because his victory might cast doubt on the May 2022 elections.

To Nomura’s ASEAN research team based in Singapore, “a Marcos victory will likely be viewed negatively owing to perceptions against him, in part because his candidacy is facing some petitions for disqualification on grounds of making false statements and a previous conviction of failing to file income tax returns.”

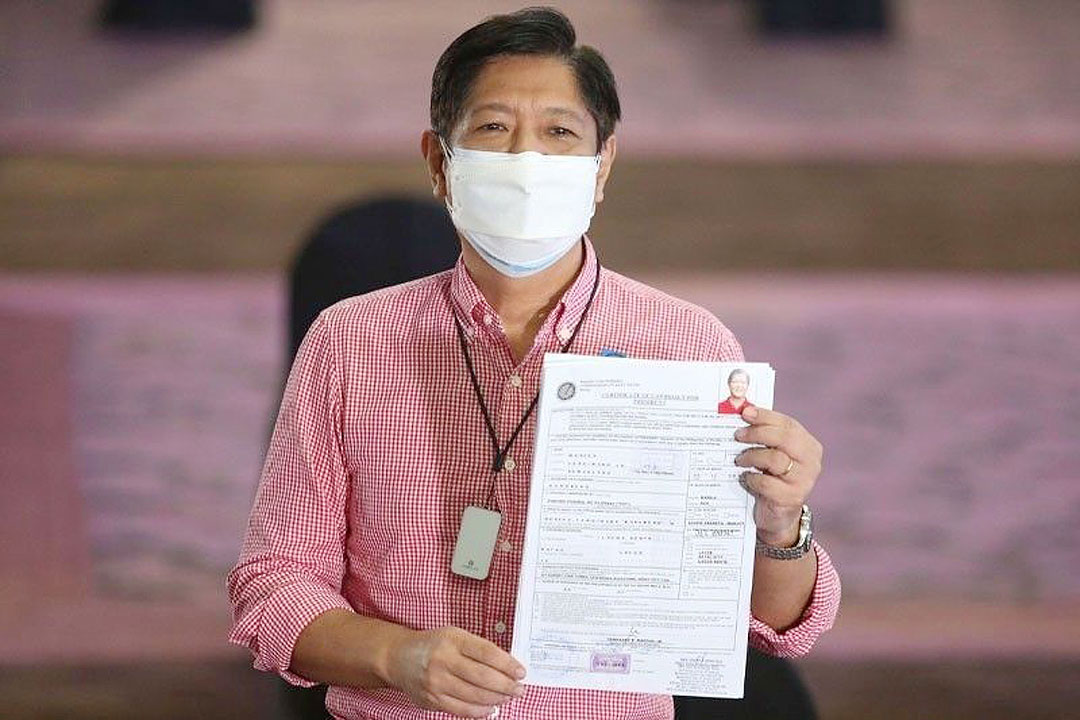

Indeed, there is not only one petition but seven petitions questioning the qualifications of Marcos Jr. as candidate for president. Seven petitions were filed with the Commission on Elections (Comelec) for the invalidation of his candidacy. Of these petitions, four wanted him disqualified on the basis of his 1997 tax conviction. Two petitions asked Comelec to cancel his certificate of candidacy (COC) on account of his conviction and therefore ineligibility to run for public office. One petition is for him to be declared as nuisance candidate because “his purpose was mainly to have his family’s political comeback in Malacañang.” This last one was dismissed by the Comelec outright.

To Nomura, choosing Marcos is choosing uncertainty as to the possible outcome of the May elections. His scores in Nomura’s rating of the presidential bets and their running mates paled in comparison with Robredo and Senator Kiko Pangilinan’s performance. They topped all the teams in all the five criteria of national experience, business friendliness, fiscal discipline, infrastructure progress, and continuity/good governance.

Marcos Jr. and Sara Duterte’s team obtained four out of five in infrastructure progress but only three out of five in fiscal discipline and continuity/good governance. They had dismal ratings in national experience, even lower than Senators Ping Lacson and Tito Sotto; and in business friendliness, they had the lowest score among all the other teams.

The other issue of uncertainty focuses on platforms of government. Except for his brief comments on specific issues of the day, Marcos Jr. has not exactly bared his platform of government. As late as December last year, when approached by a CNN reporter for an interview on his business and economic platform, he declined, reasoning that he had nothing much to say.

A month earlier, Marcos Jr. failed to attend the 47th Philippine Business Conference and Expo. This could have been a great occasion to give the business community a glimpse of his vision. All the other presidential candidates showed up to present their respective plans on what the Filipino people could expect from them in the first 100 days in office if elected chief of state.

The Nomura report raised the issue of uncertainty even as Marcos Jr. is leading many national surveys. The Nomura economists must have recognized that his campaign strategy seems to have bypassed the traditional media where fact checking and editorial supervision normally operate, and has leveraged on social media and reached out directly to the people with its own narrative. Sadly, the narrative does not conform to both history and facts. Martial law as proclaimed by his own father Marcos Sr. really happened with all the violations of human rights and confiscation of private corporations. Contrary to the Marcos family’s claim that their wealth came from Marcos Sr.’s fabulous legal fees, there are enough laws and court rulings that contradict the family narrative that until today continues to dominate social media, especially YouTube.

But following the kind of narrative that is being peddled to the Filipino people, there is a more fundamental, more difficult issue if Marcos Jr. wins the presidency.

Winning an election represents not only an ascension to power, but also a curtailment of one’s private rights and freedoms. Few people realize this. As a private citizen, Marcos Jr. is virtually free to criticize government institutions and revise history based on his own whims and opinions, no matter how unfounded.

But what happens if he becomes the Chief Executive? How would he implement various laws with respect to martial law and its atrocities which he continues to deny? How would he abide by the various court rulings that unequivocally declared the family’s wealth ill-gotten from public treasury?

The irony of it all is magnificent: Marcos Jr. — who has repeatedly failed to acknowledge the martial law atrocities and plunder of the nation — would now be charged by the Constitution to enforce the very laws that recognize what he denies.

For instance, RA 10368, approved on Feb 25, 2013, provides for reparation and recognition of victims of human rights violations during the Marcos Regime. Also known as the “Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013,” the law overturns nearly everything that Marcos Jr. has denied knowing, much less, admitting.

Marcos Jr. will be challenged in implementing this law because it declared it a state policy to “recognize the heroism and sacrifices of all Filipinos who were victims of summary execution, torture, enforced or involuntary disappearance and other gross human rights violations committed during the regime of former President Ferdinand E. Marcos covering the period from Sept. 21, 1972 to Feb. 25, 1986 and restore the victims’ honor and dignity.”

No less than Congress acknowledges its moral and legal obligation to provide reparation to the victims and their families as well as those whose properties or businesses “were forcibly taken over, sequestered or used, or those whose professions were damaged…”

There is another formidable challenge to Marcos Jr.

Section 27 of the same law mandates the establishment, restoration and preservation of a museum, library, and similar institutions in honor of the human rights victims during the Marcos Regime. Thus, a Freedom Memorial Museum is about to rise on a 1.4-hectare lot in UP Diliman under the auspices of the Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission.

As its Executive Director Carmelo Crisanto explained, a state-sponsored museum perpetuating the atrocities of military rule is “akin to the government apologizing for unleashing state forces upon hapless citizens — and a reminder for succeeding administrations not to make the same mistake.”

Will Marcos Jr. attend the inauguration of this Museum, and commit to allocate a sufficient amount in the General Appropriations Act, to supplement the initial funding of P500 million of the Memorial Commission, knowing that its vision is to enable our civil society to know and be reminded of martial law as a “way of promoting good governance towards just, humane and democratic society”?

What about the issue of ill-gotten wealth?

Former Chief Justice Artemio V. Panganiban in his Inquirer column made it easier for everyone to keep track of court rulings with a common theme: the Marcos family accumulated ill-gotten wealth.

For instance, the Supreme Court in the Republic v. Sandiganbayan (July 15, 2003), penned by Justice Renato C. Corona, forfeited $658 million owned by Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos in favor of the Philippine Government. Kept in multilayers of front foundations and organizations, the Court ruled the amount was not in proportion to the “known lawful income of the (Marcos couple from 1965-1985) since they did not file any Statement of Assets and Liabilities, as required by law, from which their net worth could be determined.” Their lawful income only totaled $304,372.43. Anything above this was deemed ill-gotten.

Other Supreme Court rulings which forfeited assets and other properties held by Marcos’ cronies to the Philippine Government proved that the Marcos era as “well-entrenched plundering regime of 20 years.” While the Marcos family also won some cases at the High Court, it was because of the prosecutors’ utter failure to observe simple procedural and evidentiary rules, to use CJ Panganiban’s own words.

So far, everyone should know that more than P170 billion has already been recovered by the government, which puts to rest the issue of whether there is stolen wealth or not. However, more than P100 billion remains hidden and awaiting recovery from the Marcos estate. Will a Marcos Jr. presidency result in its return to the Philippine government?

To be sure, the issue goes beyond Nomura’s uncertainty. It is also beyond an existential dread because all these years, Marcos Jr.’s credo was consistently counter to history and our body of laws. It is up to the Filipino electorate to decide on the side of history and avoid this fruitless irony.

Diwa C. Guinigundo is the former deputy governor for the Monetary and Economics Sector, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP). He served the BSP for 41 years. In 2001-2003, he was alternate executive director at the International Monetary Fund in Washington, DC. He is the senior pastor of the Fullness of Christ International Ministries in Mandaluyong.