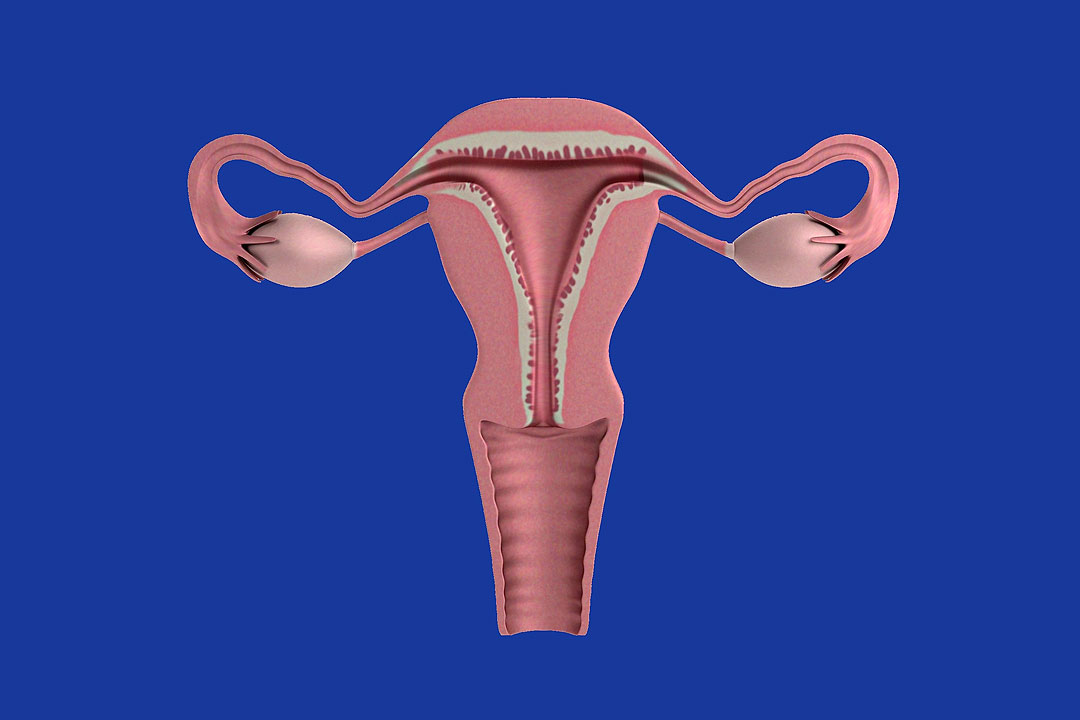

A study found that only 22% of women in Asia Pacific are knowledgeable about cervical cancer, which is preventable.

Low- and middle-income countries account for 90% of cervical cancer deaths, Allison Rossiter, managing director of Roche Diagnostics Australia, said at a forum on March 1.

In the Philippines, most women have not been screened for cervical cancer, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

By 2030, the WHO hopes to have 90% of Filipino women screened for cervical cancer.

Societal pressure influences life-changing decisions of women in the region, the Roche study noted.

“This is entirely preventable, and it’s down to education,” Ms. Rossiter said.

In a patriarchal society, women sometimes have to ask permission from their husbands, said Tofan Widya Utami, an obstetrician-gynecologist of the University of Indonesia.

“We have to give more effort on improving the education of people, especially the husbands, on the [importance of] health screening,” she added.

Ms. Rossiter said that many women are still pressured by family and societal expectations, especially “on when they should marry or if they should have a career.”

“There are conflicting messages about that,” she said.

Mridu Gupta, chief executive officer of the Cancer Awareness, Prevention and Early Detection Trust, also noted how women deprioritize their health for loved ones.

“Women are caregivers, and [low] in the list of priorities,” she said at the forum. “If resources are limited, then they prioritize the breadwinner over the caregiver.”

Each woman has the right to healthcare, Ms. Gupta said.

“You have the right to it. Make sure you speak up. Keep yourself aware of what’s happening in the world and in your body, and take action.”

BIGGER BUDGET

In a related development, the Cancer Coalition Philippines is asking Congress to increase funds for the cancer control program “so that the Department of Health, as main implementor, can carry out the provisions of the four-year old National Integrated Cancer Control Act (NICCA).”

“The law is good only on paper if it remains unfunded. We are thankful for the budget we now have but we need to increase it based on the data we have,” Carmen Auste, Cancer Coalition vice president, said in a statement.

According to the group, the Health department was “given about P1 billion in previous years to fight cancer but even for breast cancer alone, with 27,000 new cases and 9,000 deaths here annually, that amount needs to be augmented.”

For his part, Teodoro Padilla, executive director of the Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Association of the Philippines, said that funding the law can help improve the whole process of cancer control, including access to medicines.

“Only 13% of new drugs find their way locally although they are already available in other countries. Cancer is something we could live with and not die from. But we need all the tools at the disposal of the patients,” he said.

“Access delayed means treatment denied,” he added. — Patricia B. Mirasol