The View From Taft

By Zorayda V. Ang

While stuck at home under the enhanced community quarantine (ECQ), I took the opportunity to clean my desktop of old files. I chanced upon a 2007 article by David J. Snowden and Mary E. Boone entitled, “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making,” published in Harvard Business Review. Snowden and Boone introduced the Cynefin (pronounced ku-nev-in, a Welsh word for habitat/place) framework, a decision-making framework that allows leaders to “sense which context they are in so that they can not only make better decisions but also avoid the problems that arise when their preferred management style causes them to make mistakes.” I thought it would be interesting to look into how leaders have responded to this unprecedented crisis brought about by COVID-19 using the lens of the Cynefin Framework.

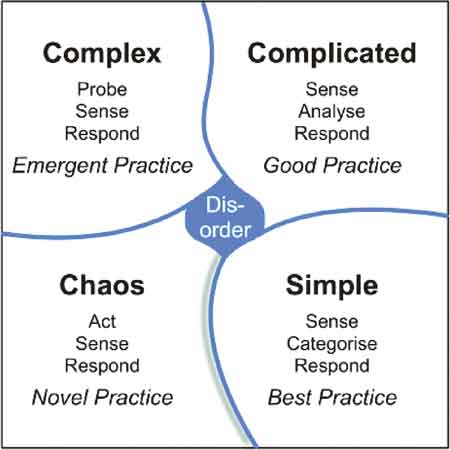

The framework consists of five domains representing the operative contexts that leaders may be in: simple (bottom right) and complicated (upper right) for “ordered” systems; complex (upper left) and chaotic (bottom left) for “unordered” systems; and disorder at the center.

The simple domain (changed to obvious in 2014) represents clear cause-and-effect relationships. The right answer exists. The leader should sense (assess the facts), categorize, then respond by applying best practices (e.g., loan payment processing).

The complicated domain is characterized by known unknowns. Cause-and-effect relationships are not immediately apparent and require experts’ diagnosis. Leaders must sense, analyze, and then respond by applying good (not the best) practice, as there are several different legitimate ways of doing things with the right expertise (e.g., searching for oil or mineral deposits).

The complex domain represents cause-and-effect relationships that are obvious only in hindsight; no right answer exists, just emergent instructive patterns with safe-to-fail experiments. Leaders need to probe first, sense, then respond. The authors note, “Leaders who try to impose order in a complex context will fail, but those who set the stage, step back a bit, allow patterns to emerge, and determine which ones are desirable will succeed. They will discern many opportunities for innovation, creativity, and new business models” (e.g., YouTube’s streaming video technology).

The chaotic domain is characterized by high turbulence. With no clear cause-and-effect relationships, it’s pointless to look for answers. Leaders must immediately act to reestablish order, sense where stability is absent or present, then work to transform the situation from chaos to complexity (e.g., responding to the Sept.11, 2001 event). Chaos impels novel practices.

The central space, disorder, is not knowing which of the domains you are in. The response to the situation is based on the leader’s personal preference.

The authors warn that leaders often move to the complacency zone (the boundary between simple/obvious and chaotic) when things appear fine, thus missing what is really happening and reacting too late. As a result, leaders fall over the edge in a crisis, and recovery is very expensive.

A good example of this is how leadership at the Department of Health incorrectly categorized and oversimplified the COVID-19 issue into the simple/obvious domain. The declaration of a public health emergency came too late in March despite the World Health Organization’s declaration of COVID-19 as an international public health emergency in January. The result was chaos. The President immediately took to media to stop the early panic by keeping citizens informed. Subject matter experts were called in (complicated) to get better outcomes. The Inter-Agency Task Force and sub-task forces were created. Science and data were trusted more than ever as tools for decision-making. Leaders from across all sectors, including communities, had to calm their people by giving assurance of safety and stability (complex) — a most challenging task indeed. They stepped up and responded to the changing conditions with increased communication and interaction with people. The compliance by businesses and the citizenry with government measures showed support for the decisions made.

This COVID-19 pandemic has become the ultimate test for our leaders across sectors. We are still at the complex domain as leaders continue to face critical decisions to balance competing priorities with inclusivity and compassion. Let us continue to cooperate and support our leaders as they craft recovery measures and interventions to transition to the “new normal.”

Dr. Zorayda V. Ang teaches Management Principles and Dynamics in the MBA Program of the Ramon V. Del Rosario College of Business of De La Salle University.