PHL declines in global economic freedom index

By Kyle Aristophere T. Atienza, Reporter

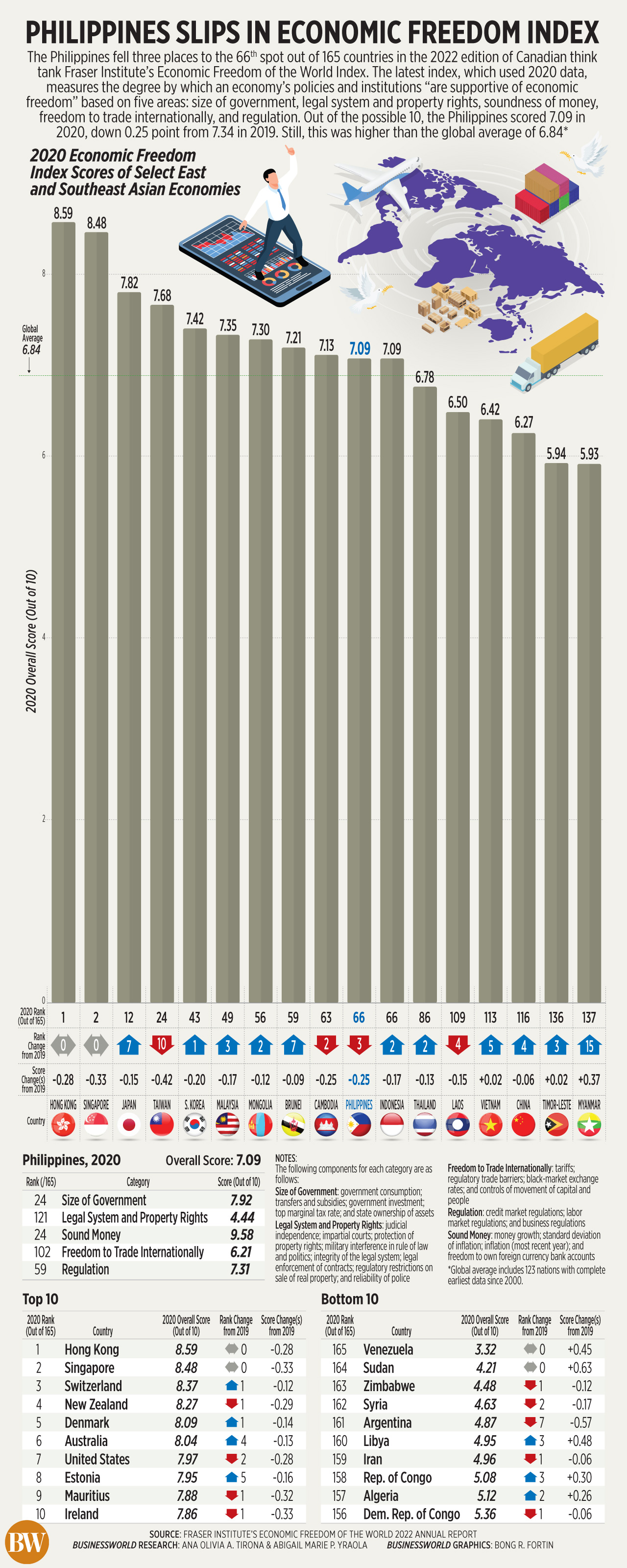

THE PHILIPPINES’ economic freedom ranking dropped three places, amid lower scores for regulation and trade freedom in a global report measuring 2020 data.

The Philippines ranked 66th out of 165 economies in the Canadian conservative think tank Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom Index for 2020 with a score of 7.09. The score is 0.25 point lower than its 7.34 score in the 2019 index.

The index measures economic freedom based on five categories — sound money, size of government, legal system and property rights, freedom to trade internationally, and regulation.

The Philippines performed best in the category of sound money with a score of 9.58, higher than the 9.56 score in the previous index. This category covers money growth, inflation and freedom to own foreign currency bank accounts.

The Philippines performed best in the category of sound money with a score of 9.58, higher than the 9.56 score in the previous index. This category covers money growth, inflation and freedom to own foreign currency bank accounts.

On the other hand, the country’s lowest score was for legal system and property rights at 4.44, as the impartiality of Philippines courts weakened.

For size of government, the Philippines’ score declined to 7.92 from 8.16 previously as it saw a drop in the government consumption score.

In terms of freedom in international trade, Manila’s score dropped to 6.21 in 2020 from 7.07 previously. This was mainly due to lower scores on tariffs and controls on the movement of capital and people.

To recall, the government implemented strict lockdowns in 2020 to curb coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections.

The Philippines’ score on regulation slipped to 7.31 from 7.48, with a major decline in credit market regulations and private sector credit.

The Philippines, which shared the 66th spot with Indonesia, lagged behind Southeast Asian neighbors such as Singapore (2), Malaysia (49), Brunei (59), Cambodia (63). However, it was ahead of Thailand (86), Vietnam (113) and Myanmar (137).

The Fraser Institute noted that many nations in Latin America and Southeast Asia scored low in terms of rule of law and property rights.

“The nations that rank poorly in this category also tend to score poorly in the trade and regulation areas, even though several have reasonably sized governments and sound money,” it said.

Hong Kong dominated the economic freedom index, followed by Singapore, Switzerland, New Zealand and Denmark. Venezuela, on the other hand, was the country with the least economic freedom.

“The index attempts to measure the strength of our institutions in preventing political corruption and other practices such as bribery, extortion, nepotism, cronyism, patronage, embezzlement, and graft,” Leonardo A. Lanzona, who teaches economics at the Ateneo de Manila University, said in a Messenger chat.

Mr. Lanzona noted “maneuvering” of independent institutions during the previous government was a major threat to economic freedom.

“This failure to enforce the rule of law is detrimental to our economic performance.”

Mr. Lanzona noted the index tracks the “crumbling” of Philippine democratic institutions, which Congress has enabled. “The only way this will change is to strengthen the checks and balances in our institutions.”

Zyza Nadine Suzara, director of governance think tank I-Lead, also believes that the decline in ranking of the Philippines reflects “a serious problem” in governance as seen in the previous administration.

“It is lamentable that with regard to this, we also pale in comparison to our ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) neighbors,” she said in Messenger chat.

She said the 2020 data should prompt the Marcos administration to pursue good governance reforms and ensure that his government would not side with any businesses.

“The new administration faces a huge challenge of overturning how the country performs in these indices. This can only happen if the new administration commits to reform institutions which have been damaged,” she said.

Renato E. Reside, Jr., an associate professor at the University of the Philippine School of Economics, said the index reflects the perceptions of several major risks about the Philippine economy. He cited the degree of political and expropriation risks, weaknesses in contract enforcement, and corruption.

“The very low score on judicial independence aggravates the ranking. These may explain the persistent difficulty in attracting investments to our country — there is a nontrivial risk of political intervention in business and markets, slow speed in judicial decisions as well as lack of fairness in the enforcement of laws, which raises the risk and adds complexity and cost of doing business,” he said.

Mr. Reside noted that the decline in trade score is a result of the perceived level of trade protection for Philippine industries as well as the lack of participation in recent emerging trade groups.

How the government handles recent trade issues in agriculture markets “will be important determinants of trade freedom in the future,” Mr. Reside said.

Meanwhile, Mr. Lanzona said the government can prove its commitment to improving its scores in the legal system and property rights by restoring the original functions of the Presidential Commission on Good Governance, which lawmakers now want to abolish.

The late president Corazon C. Aquino created the PCGG in 1986 to go after the ill-gotten assets of the late dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos, his family and cronies.

The PCGG was established after a popular street uprising toppled the late dictator’s regime in the same year, which sent the elder Marcos and his family into exile in the United States.

“There should be a commitment to uphold the rule of law,” Ms. Suzara said. “But with the Marcos family’s history, it is difficult to remain optimistic about good governance.”