Getting real to tackle the climate crisis

IN 1962, former South Korean President Park Chung-hee said, “if you can see factories fuming out gas, it is a sign of advent success.” It was a metaphor for industrialization. The dominant business model at that time delivered private profits, while creating public losses in the form of externalities, mainly environmental degradation. The same trend happened everywhere across the globe. That was the zeitgeist of the 20th century, so it is futile to dwell on the past. People did not know what was wrong with it, because the whole system that ignored negative spillovers encouraged reckless economic development without knowing how it drove us into danger zones close to “planetary boundaries.”

Several decades later, however, we received a guilty verdict. The scientific consensus was clear on anthropogenic climate change. The setback was more than expected — climate change with catastrophic effects, and is now exacerbated by the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, which was also triggered by human disregard for planetary boundaries. Now we have a strong reason to fix our planet and build back better. One priority action is to reach net zero emissions by 2050, which is based on the scientific consensus from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

NET ZERO 2050 REQUIRES SYSTEMIC CHANGE

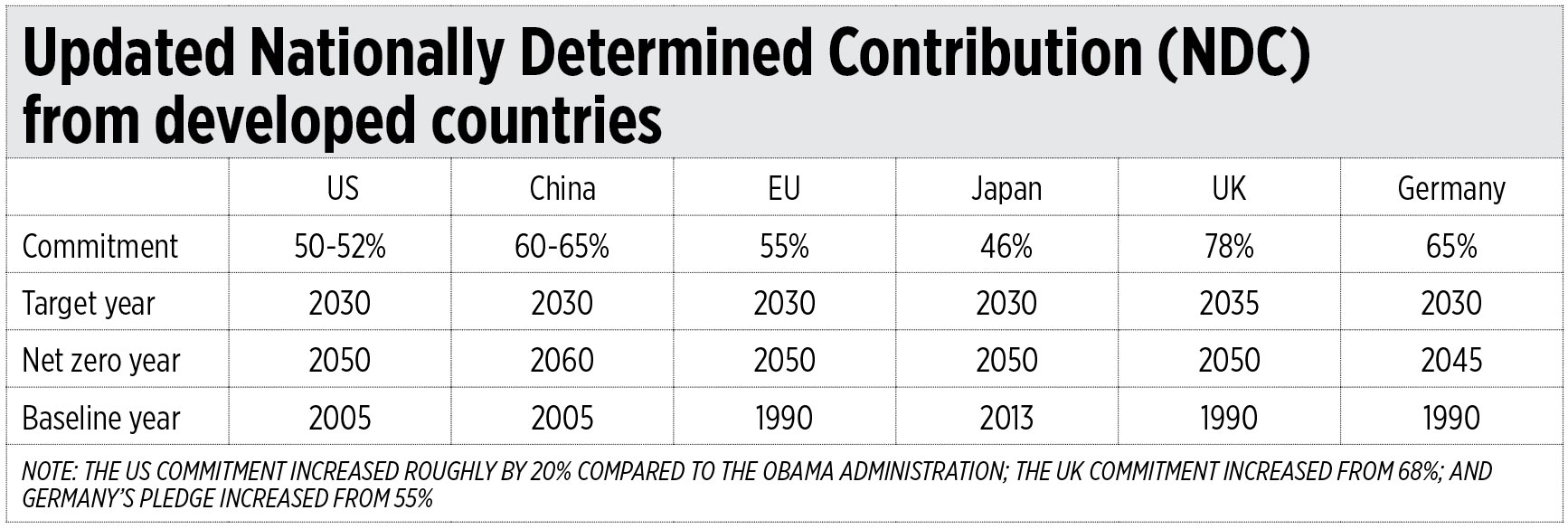

On April 23, US President Joseph Biden called up the world leaders to talk about this issue. Acknowledging the longstanding criticism on their deviation, the United States returned, not simply to the negotiation table but with an ambitious plan — 50%-52% greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction by 2030 compared to 2005 levels. A few countries welcomed the US by unveiling more ambitious plans by 2030, as can be seen in the Table. To keep the momentum for successful negotiations towards the Glasgow Climate Conference (COP 26), the Partnership for Green Growth (P4G) Seoul Summit meeting later this month will also be held, along with growing international expectation of additional ambitious commitment from countries, including the host country.

The year 2030 is an important milestone given the urgency, since global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions should decline by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 to reach net zero around 2050. Bill Gates, in his recent book, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, however, warned that reductions by 2030 done the wrong way might prevent us from ever getting to net zero. He pointed out that replacing coal-fired power plants with other gas-fired power facilities for the sake of meeting the 2030 timeline will indeed reduce our emissions by 2030. However, any gas power plants built at this time will continue to be in operation come 2050 emitting out toxic gases. So, we need to realize that the net zero race towards 2050 is not just about near-term political or environmental rhetoric. Instead, it is about the systemic transformation of the economy for the long term.

For governments, after setting the targets, the next step is to develop concrete policies to realize them. Using the climate rhetoric on one hand while doing business as usual on the other is contradictory. Every sector in the economy must take bold steps forward, especially the high-polluting sectors such as energy, waste, agriculture, transport, and building, among others.

NET ZERO IMPLICATIONS FOR THE BUSINESS SECTOR

Alignment to net zero is not the realm of the public sector alone. Systemic problems like the climate crisis require systemic solutions, to which the private sector has a lot to offer as they account for two-thirds of the global economic system. Addressing the climate challenge requires us to change the way we produce, consume, commute, eat, and even interact with each other — and this is a race against time.

Paul Polman, a former CEO of Unilever said, “business cannot succeed in societies that fail.” Some industries have been leading this race. Most of car manufacturers are going electric. In its recent report, Technavio, a global market research firm, said the global electric vehicle battery market is expected to grow by $37.69 billion, exhibiting a compound annual growth rate of over 18% during 2021-2025. Solar power has been growing rapidly for the last few years in the US, China, and globally, boosted by continuously dropping prices breaking new records. From an optimist’s standpoint, there is an expectation that solar and wind energy could replace fossil fuels entirely by 2050, according to a new report by Carbon Tracker.

In the meantime, traditional industries are facing pressure to reduce emissions from their supply chains. GHG emissions in industry are generally categorized into three scopes by the widely used international accounting tool, the GHG Protocol. Scope 1 covers direct emissions from controlled sources of a business, while Scope 2 covers indirect emissions such as the generation of purchased electricity, cooling, and heating consumed by the reporting company. Scope 3 includes all other indirect emissions that occur in a company’s value chain — which still requires efforts to develop a methodology.

Recently, for instance, Indonesian ride-hailing giant Gojek announced their sustainability plan to make every car and motorcycle on their platform an electric vehicle by 2030. The company is also looking into reducing their emissions across their supply chain. Microsoft declared in early 2020 that they will be carbon negative by 2030, and by 2050 they will remove from the environment all the carbon the company has emitted either directly or by electrical consumption since 1975. Apple is committed to be carbon neutral across its entire business, manufacturing supply chain, and product life cycle by 2030. This implies that there are available clean technologies that can be applied to reduce emissions across the Scopes, such as retrofits, energy efficiency, and the like, and more solutions are being developed.

This trend will spread over the several industries. Soon leading companies will be voluntarily assessed (and ultimately regulated) on where the emission hotspots are in their own supply chain. They will identify which suppliers are a fit with their sustainability actions and which are laggards. This will naturally create a cascading effect among the supplier companies — in most cases micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs).

Getting sustainability embedded in the heart of core business operations is no longer an ethical question, but more about the issue of survival and raison d’être in a transforming market that affords more value to sustainability, not just as part of corporate social responsibility but as a mainstream business proposition. The rise of the B Corporations — certified businesses that meet the highest standards of verified social and environmental performance to balance profit and purpose — and impact /ESG investment are good examples.

TOWARDS GENUINE GREEN INVESTING

In the race towards net zero, many companies have expressed their commitment. As of April 2021, over 2,000 businesses joined the UN Race to Zero campaign, which mobilizes the largest alliance of cities, businesses, and academic institutions committed towards the 2050 goal. However, these commitments have yet to be translated into genuine climate action.

Big banks committed to net zero continue financing the fossil fuel industry in 2020, even more than they did in 2016 and 2017. BlackRock, the world’s biggest investment fund manager, operating assets of $8.7 trillion (as of December 2020), committed to support net zero and pressure others to do so — but its “Carbon Transition Readiness” fund includes fossil fuel giants. Carbon offset commitments from companies sound good in theory, but it is uncertain whether those plans and their associated accounting are robustly monitored and evaluated.

On the other hand, achieving net zero requires an enabling environment for businesses to thrive amid the painful tradeoff of the green economy transition. Government support in the form of subsidies, regulations, incentives, and the like towards clean industry can enable the transition. On top of that, a crucial strategy to accelerate the transition is strengthening the entrepreneurial ecosystem, specifically focusing on green startups as their values are well aligned with the net zero vision and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Now, about the Philippines. The Government of the Philippines submitted the country’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) on April 15, promising to cut its GHG emissions down by 75% from 2020 to 2030 compared to the business-as-usual scenario of the same time period, focusing on agriculture, waste, industry, transport, and energy sectors. Of the 75% target, 72.29% is conditional dependent on support from developed countries.

To jump on the net zero race while recovering from the pandemic, it seems even more important for the public and private sectors in the Philippines to work together with international development partners to proactively originate climate projects that generate transformative impacts, effectively mobilize international climate finance (e.g., the Green Climate Fund), and implement those projects on the ground with well targeted beneficiaries.

The vision of the world in 2050 is not the same as how our leaders foresaw the future in the 1960s. The future we want for our generation and the next is that of a healthy and resilient planet, which can only be realized by staying genuine to our commitment. It is time to get real.

This op-ed does not necessarily represent the opinion of any organization, but is a personal opinion of the author.

Juhern Kim is the Country Representative to the Philippines of Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI).