A Filipino classic comes home

BOOK REVIEW

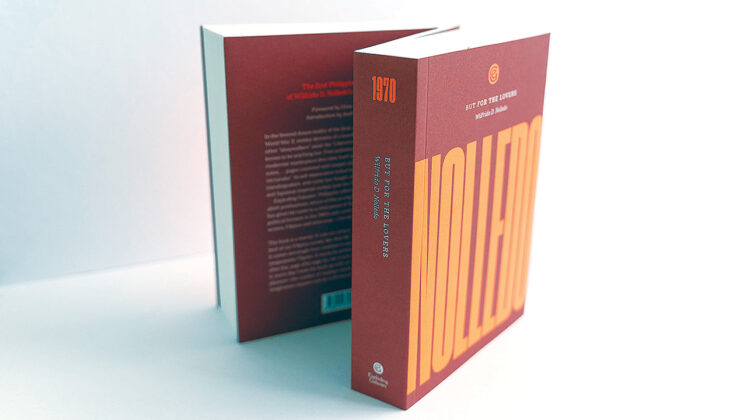

But for the Lovers

By Wilfrido D. Nolledo

Exploding Galaxies, 440 pp

THE DAY I hunkered down to read the new and ridiculously overdue Philippine edition of Wilfrido Nolledo’s “lost” masterpiece But for the Lovers was the day of the Manila Central Post Office fire. When people woke up to harrowing footage of massive flames gutting the interiors of the pre-war structure, its austere neoclassical columns and ornate cornice beat and blackened by thick billowing smoke.

The last time the building endured similar damage, many were quick to point out, was during the apocalyptic Battle of Manila, which is also the grueling, convulsive climax of Nolledo’s famously demanding novel, first published by E. P. Dutton in 1970 then reissued a quarter of a century later by Dalkey Archive in 1994, a decade before Nolledo died in California in 2004.

From the first and only time I tried to read the book more than a decade ago, what survives is a vague memory of being astounded by the Manila resurrected in it, ill-equipped as I was to “get” everything.

Reading it now, this also became my initial point of entry. I absently waited for the post office to make an appearance amid the languid, scrupulous flânerie through which it maps the occupied city: the looting and scavenging and breadlines, “Japanese soldiers tramping on pavements” on Avenida Rizal, Intramuros “maimed forever” by tanks and convoys, the nasty violence at the internment camp in UST, the periodic air raids during which “the sky overcasts with bombers.”

But also, we are told: “envoys in aloha shirts [gorging] themselves with huge bowls of mami” on Calle Salazar, “matronly entrepreneurs” buying and selling jewelry with “huge bayongs heaping with paper money” in Divisoria, local and foreign patrons trooping to a “brick-and-banyan polyglot period piece” on Raon to watch a famous belly dancer.

It is a place brutalized but also bored and business-as-usual, “deafened by sirens and strafings” and “astir with Nipponese army and moving with American bombs,” but also peopled by “skeletons roaming the sidewalks, dreaming of American Invaders,” erstwhile colonizers who are “always coming” but whose promised arrival is “as distant as the moon.”

Manila drawn this way, adrift in a war dizzyingly planetary and heinously local, is a primal pleasure in the book, the capital’s history of ruin and survival palpable in the chaotic present. And viewed from today’s megalopolis, interminably besieged by the brutal force of capital even during peacetime, its built heritage always on the verge of banal destruction, war is generative metaphor.

A microcosm of Nolledo’s surreal world is the creaking but buoyant Ojos Verdes boardinghouse, a “two-story monstrosity pasted together with adobe and aluminum” that had seen better days, a “Shangri-La for sectless shamans” where “lodgers desultory and deregionalized flitted in and out.”

The three main characters share one room (13 — the novel not shy with its auguries): the wistful, pathetic Spanish theater veteran Hidalgo de Anuncio; the wily scavenger who is “so ugly it hurt the eyes” Molave Amoran; and a delicate young woman who spends most of the novel nameless and seemingly asleep.

Other than the morose wait for the inevitable “liberation” of the city, the afable tug-of-war between Hidalgo and Amoran over Alma — the woman — may be the only steady narrative line here, tenuous as it is. At one point, the two offer their respective worlds to Alma, as if she were an empty vessel:

“Like a guidon Hidalgo introduced her to a Spanish thesaurus. She was taught grammar, syntax, conjugations in the morning; at night she absorbed the adenoidal dialects of a city that Amoran slit open to her like a goiterous throat. Her mornings were mannered and orchidaceous with Hidalgo’s invocations of dons and dowagers; her evenings were malodorous, were morbific with Amoran’s influx of urchins and lepers. Two heads had her deity.”

It’s sequences such as this that invite the sort of pat nation-nation allegorical reading to which But for the Lovers is often subjected, and which Gina Apostol, in her capacious Foreword, decries: “Reading Laura in Balagtas, Maria Clara in Rizal, and Alma in Nolledo as allegories of motherland disturbs me … the conjoining of women with violence and oppression in this allegorization of nation is a reduction that, in my view, does not read Rizal, Nolledo, or the nation as well as one could.”

It doesn’t help that such gestures abound: when Hidalgo, Alma’s “discoverer,” whispers “Hija” to her, the word is said to be “caressed … by four hundred years of Spanish romance”; the arduous mission to transport an American pilot from the north back to the city turns almost touristic with someone’s thesis on “the mountain culture” and what it signals for the Filipino; the boardinghouse is “regionalized” between “ground-floor Southerners” and “second-story Northerners” who debate on “their star placements on the three-star Filipino flag”; even Rizal’s fiction and life make an appearance in a POW’s hallucinatory soliloquy.

The casual, overwrought, often needless brutality that women’s bodies have to endure in the novel, which Apostol helpfully contextualizes, also doesn’t help.

Most characters, however temptingly archetypal, thankfully benefit from Nolledo’s otherwise deepening, individuating portraiture. A favorite presence is Tira Colombo, the huge, horny landlady of Ojos Verdes who enters the novel rolling out of her sagging bed bemoaning a lackluster encounter (“she had supervised the love-play; he’d simply melted away”). Delinquent tenants can settle their obligations this way, which she tracks on a ledger filled with helpful marginalia — “niñgas-kugon for flash-in-the-pan; hilaw-na-hilaw was still-wet-behind-the-ears; barako meant brute, the ideal category.”

Other figures, in varying states of weariness, crowd and construct the world: a loquacious one-armed POW at the UST camp, a skilled American pilot turned feckless “symbol,” a ragtag army of “underground hotheads” killing Japanese soldiers and bombing munitions trains after dark, a soft-spoken horse-riding Japanese officer “longing to be murdered,” a tranvia conductor also conducting “Manila’s underground orchestra,” a locksmith named Zerrado Susi, etc. etc.

This cacophony — and Nolledo’s command of voice is singular — offers another entry point to the book, and toward unpacking how it makes sense of its arguments about history.

The idea of war as both monstrous and mundane, savagery and stupor, is beguiling, probably necessary for a project like Nolledo’s, which deliberately directs the shrapnels of one war outward, to sporadically illuminate the rest of Philippine history.

Here, the agony of the Japanese Occupation converses with crumbling Hispanic nostalgia. Pragmatism jostles against “politics, government, religion … big, fat gobs of one rotten yolk.” And the genocidal “liberation” of Manila is textually entwined with the first time the self-same American empire came half a century earlier — an “inexorable doubling” toward the book’s climax that, Apostol writes, “doubles one over with history’s grief.”

(In an early scene, “desiccated old men” who were “patriarchal echoes of the Revolution” huddle under Hidalgo’s window after being waylaid by a foiled operation — more signals of the novel’s sense of empire’s coherence and calculated continuity.)

Particularly instructive is the figure of Amoran, the novel’s monstrous everyman, looting and foraging through the scraps that litter Manila’s barren landscape, swimming in ponds for kangkong, salvaging animal entrails from the talipapa, selling dug-up nails to talliers in Binondo and mowed grass to stables in Galas. In other words, the dirty work that keeps Hidalgo and Alma and other people around them alive.

Such nocturnal trawl through ruins — not to mention the final escape as American bombs finally rain on the city — speaks to a key facet of our historical experience, Filipinos as “survivors, imperishable through laws and rainstorms,” so banally, existentially captured by Nolledo thus: “During these crucial months of the Japanese Occupation, rumor had it that Filipinos were still alive in Manila.”

And all of it orchestrated by the kind of fervid, hypnotic, untiring prose that in itself is a site of this violent history, an English overloaded with a Filipino writer’s keen sense of irony, play, and delight in multiple tongues — busabos boys, eskinita hymns, at saka didn’t he already…, anak ng kwago the Americans are coming! There is not one flat paragraph here, in style as in thought.

This narrative bravura — reminiscent of anyone from Carpentier and Genet to Joyce and Morrison, with Joaquinesque set pieces here and there — of course means the book’s readership will be select, although even at its most prolix, it is never completely impenetrable. These and many other points of entry — of visceral pleasure, of profound historical pain — should open up But for the Lovers to readers who are willing to participate in Nolledo’s fever dream of brutality, fatigue, grit, and transcendence.

The first Philippine edition of Wilfrido D. Nolledo’s But for the Lovers is available at www.explodinggalaxies.com.

Glenn Diaz’s first book The Quiet Ones (2017) won the Palanca Grand Prize and the Philippine National Book Award. His second novel Yñiga (2022) was shortlisted for the 2020 Novel Prize. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Rosa Mercedes, Liminal, The Johannesburg Review of Books, and others. He is a recipient of residencies in Bangalore, New York, Hong Kong, and Jakarta. He teaches literature and creative writing at the Ateneo de Manila University and holds a PhD from the University of Adelaide. He lives in Quezon City.