Copyright fight: Ballet Philippines risks losing ‘treasure trove’ of dance

By Sam L. Marcelo, Multimedia Editor

THE ACRIMONIOUS relationship between the board of Ballet Philippines (BP) and the company’s founder, National Artist for Dance Alice G. Reyes, has turned litigious, prompting choreographers to copyright their creative work to prevent BP from claiming ownership of their dances.

Ms. Reyes, who was named a Gawad Yamang Isip Awardee by the Intellectual Property Office of the Philippines (IPOPHL) on June 6, has been helping dance artists protect their work. Her crusade picked up steam after one of her pieces became the subject of a cease-and-desist letter sent by BP.

“Filipino artists just want respect,” said Ms. Reyes, in a conversation with BusinessWorld. “Royalties would be nice but, really, we just want respect.”

Until the dispute is settled, BP’s status as a resident company of the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) is “on hold,” said Chris B. Millado, outgoing CCP vice-president and artistic director, via Zoom on June 8.

Mr. Millado, whose last official day with the CCP is on June 15, added that BP’s privileges, such as subsidies from the CCP and the use of its venues, have been under evaluation since the beginning of 2022.

The ballet company launched its 53rd season in Gallery by Chele in Taguig City this May with the theme “Dance Where No One Else Has.”

“Ballet Philippines is going somewhere where no one has danced before. … It does not just pertain to destination or location. We’re talking about the new mindset and that is collaborations with like-minded people and institutions,” said BP President Kathleen “Maymay” L. Liechtenstein, in a speech delivered at the event.

‘STAKING A CLAIM’

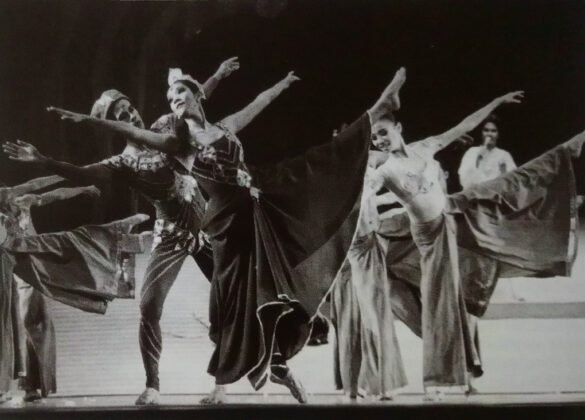

On Oct. 16, 2021, two days after Ms. Reyes’s 79th birthday, BP wrote a cease-and-desist letter to Mr. Millado demanding that CCP stop broadcasting the dance Itim Asu — a work that Ms. Reyes choreographed in 1970 and remounted in 2020 as part of the show Alice and Friends.

(See “‘Total fail’: How communication breakdown broke Ballet Philippines’ leg”)

“BP has intellectual property rights to the ballet work as it was created for BP,” stated the letter signed by Ms. Liechtenstein.

The letter also reiterated that BP “does not give consent to CCP to stream in CCP’s virtual platforms” five productions that were mounted by, or choreographed in whole or in part by Ms. Reyes.

Aside from the aforementioned Itim Asu, and Alice and Friends, BP named three shows that were produced during Ms. Reyes’s return as BP artistic director from 2017 to 2020: A Gala Celebration (2017), The Exemplars (2017), and Tales of the Manuvu (2019).

To wit: BP, a resident company of the CCP, sent a cease-and-desist letter to the CCP over Itim Asu, a dance that BP founder Ms. Reyes:

- choreographed in 1970, at the behest of the League of the Filipino Composers and the CCP, and

- remounted in 2020 with the help of a CCP grant.

“You own it from the moment you create it,” said Ms. Reyes, referring to a choreographer’s rights to a piece — in this case, Itim Asu, which is based on Virginia R. Moreno’s award-winning play The Onyx Wolf (also known as La Loba Negra). “In fact, I have the copyright.”

Ms. Reyes is quoting the IP Code, which “grants authors, artists, and other creators, automatic protection for their literary and artistic creations, from the moment they create it.”

WHO OWNS WHAT?

While BP got several important details wrong in its demand (such as when Ms. Reyes created Itim Asu and for whom), the unresolved issue between BP and the coalition of CCP and Ms. Reyes raises larger questions: Who owns a dance and who should profit from it?

It’s complicated.

If Ms. Reyes wishes to mount a new production of Itim Asu — with a different look and feel — she can. And it is also Ms. Reyes who has the power to decide who gets to restage Itim Asu.

As summarized by Mr. Millado, while Ms. Reyes owns the rights to the choreography of Itim Asu — the dance itself — she does not own the rights to the sets, the costumes, and the lighting design of the 1970 production; or the music of Alfredo S. Buenaventura.

If she wants a faithful restaging of the 1970 original, she will have to get permission from her artistic collaborators or their estates since the production’s different parts are owned by different people. And the entire production itself is owned by its producer. (Ms. Reyes got the required permissions for her 2020 restaging. Ms. Moreno was sitting in the audience, as was painter Jaime De Guzman, who designed the sets.)

Neither does Ms. Reyes own the digital file of the 2020 performance that was streamed, or the storage medium (which might be a USB stick, a flash memory card, a CD, or a VHS tape) that it was recorded on — the CCP owns those.

If she wants to upload and stream CCP’s 2020 recording on her own platforms, she will have to ask permission from the CCP.

The CCP, on the other hand, will also have to get permission from the artists and companies involved if they want to stream recordings of live performances (which it did). If the CCP decides to charge people for viewing the streamed works, then artists can ask for royalties.

And if the CCP (or BP) wants to restage Ms. Reyes’ work, they will have to get her permission as well.

Complicating matters: there was no intellectual property system in the Philippines in the 1970s — IPOPHL just celebrated its 25th anniversary on June 6 (hence Ms. Reyes’s award) — and contracts then didn’t account for, say, YouTube and other streaming services.

Goodwill was the grease that kept artistic projects going (spoiler: it still is).

“No copyright rules existed during that time, no written contracts covered ownership,” said CCP’s Mr. Millado. “It’s all retroactive — what’s happening now — and people are staking a claim.”

The pandemic, which forced the creative sector to pivot online when restrictions shuttered live performances, highlighted how recordings — previously thought of as archival material — can be monetized.

According to Mr. Millado, there are several compensation models depending on the circumstances of the broadcast. If a show is uploaded and distributed for free to the public on a specific platform for a limited period of time, the CCP informs artists and offers a token fee, which is often waived.

If the CCP charges audiences for streaming a show, then it might offer its creator a one-time royalty of 15% of their original fee for mounting the production; or pay a minimum amount, with the promise of a percentage of the profit, assuming the show earns.

“It’s more work for arts managers but that’s how you make the sector sustainable. That’s where you enter into ‘creative industry,’” he said.

“They [artists] see that there is an economic opportunity in asserting their moral rights to their intellectual property,” added Mr. Millado. “Performing artists and choreographers are still quite ambiguous about their rights, that’s why they are usually at the mercy of the ‘producers.’ … They need to know what they own, how to protect it, and how they can earn from it.”

Commenting on Ms. Reyes’ Itim Asu, the CCP artistic director said: “If there are no written contracts that say that a company owns a commissioned work or that the artist gives up moral and economic rights to a certain piece, then what prevails is the intellectual property rights law, which is that the work is the ownership of the original creator.”

According to the IPOPHL website, “registration and deposit of works isn’t necessary but authors and artists may opt to file for the copyright registration of their work with IPOPHL for the issuance of the appropriate certificate of copyright registration.”

This is a gross oversimplification of a thorny issue that is still with the CCP’s legal department and other agencies. It is also for this reason that IPOPHL cannot comment on the cease-and-desist letter.

BP did not reply to multiple requests for comment.

A BREAKUP IN THREE ACTS (AND COUNTING)

Act 1.

Cracks first began to show when the BP board passed over Ms. Reyes’ recommendations for her successor and instead appointed Mikhail “Misha” Martynyuk, a dancer of The Kremlin Ballet in Russia, as artistic director of the dance company in February 2020. (See: “The Russians are coming, the Russians are coming”)

Act 2.

Over the pandemic, the rift widened: vocal “pro-Alice” BP dancers, some with careers spanning more than a decade, were frozen out of work.

Ms. Reyes took in these displaced BP dancers, along with retrenched professionals from other dance companies, and formed a group that, through several lockdowns, conducted online classes, mounted shows, and premiered new work with support from the CCP.

Ms. Reyes mentors a corps of 18 dancers; BP, meanwhile, lists 16 on its website.

Act 3.

The tussle over intellectual property rights escalates the schism between the BP board and Ms. Reyes, taking a disagreement over artistry, tradition, and legacy into legal territory with accompanying financial ramifications.

“It’s our right as choreographers to protect our pieces and be given due credit for the hard work we put into creating them,” said Monica A. Gana, a former BP soloist and dancer-choreographer now under Ms. Reyes’ wing.

With Itim Asu turning into a cautionary tale, Ms. Gana and young choreographers like her decided to take control of their pieces, some of which were created and staged under the auspices of BP.

From 2021 to present, the Bureau of Copyright and Related Rights has issued 21 certificates of copyright registrations for literary and artistic works. Out of this number, four fall under “choreography.”

In a June 12 e-mail to BusinessWorld, Ms. Gana continued: “I felt relieved that I had an official document saying that I, as the choreographer, have the right to decide who can dance it [my piece] and where it can be danced.”

LOST TREASURE, SWALLOWED PRIDE

As word of Ms. Liechtenstein’s demands made the rounds in the dance community, artists were dismayed but not surprised at the BP board’s actions.

“I don’t think they realize that choreography is a skill,” said Agnes D. Locsin, a pioneering neoethnic choreographer, via Zoom on June 5. “They’re destroying the name [of Ballet Philippines]. … I’m waiting for them to collapse. It’s just money that’s keeping them alive.”

Named a National Artist for Dance on June 10, Ms. Locsin has been copyrighting her work since 1988.

On June 13, the BP board congratulated Ms. Locsin on its platforms, saying: “Some of Agnes’ greatest and most influential works were created with Ballet Philippines.”

The “current BP” — as Ms. Locsin calls the company under Ms. Liechtenstein — might find that showcasing the work of the newly minted National Artist a less collegial affair than it used to be.

With the “old BP,” restaging requests would be met with a nonchalant “yeah, sure,” from Ms. Locsin, a former artistic director and resident choreographer of BP.

A request from Ms. Reyes herself is even weightier: “You can’t say no,” said Ms. Locsin, trying to explain how esteemed the BP founder is by generations of dancers.

And while she is still open to working with the current BP, Ms. Locsin won’t be as accommodating: “For professional reasons, I feel like I will need to say ‘yes,’” she replied. “However there will definitely be conditions that they will have to meet — which I am sure they will have difficulty meeting.”

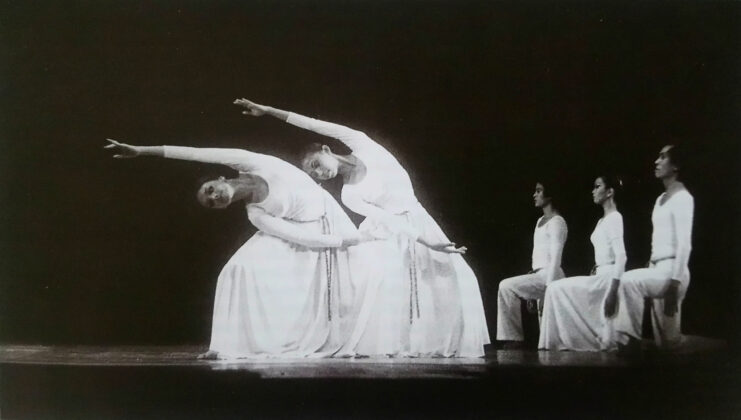

Ms. Locsin trusts only three dancers with the restaging of her work. After performing her pieces hundreds of times, their bodies remember the jagged angles of Ms. Locsin’s choreography.

“My restagers can explain dance the way I explained it to them,” she said.

This, in a nutshell, illustrates “the distinct difference between the preservation of dance and other artistic media” as the New York Times put it: “choreography often depends on an oral tradition to uphold its integrity through style, motivation and content.”

Ms. Locsin no longer sees the current BP as part of the oral tradition that she is steeped in, in part because of the way it treated Ms. Reyes.

“They have no knowledge of dance in the Philippines if they don’t value Alice Reyes,” said Ms. Locsin. “Even if you remove the title National Artist — this is Alice Reyes, the founder of Ballet Philippines.”

Ms. Reyes, in a Viber message to BusinessWorld on June 7, went as far as to call BP, the dance company that has been tied to her name since 1969, “Ballet Russe”: “Ballet Russe has lost a treasure trove, blindly insisting that it’s theirs — unless they can swallow their pride, ask permission to stage, pay a teeny royalty.”

By sending the cease-and-desist letter, BP has traded its crown jewels — its vast repertoire of modern and contemporary Filipino pieces — for a gaggle of swans.