Movie Review

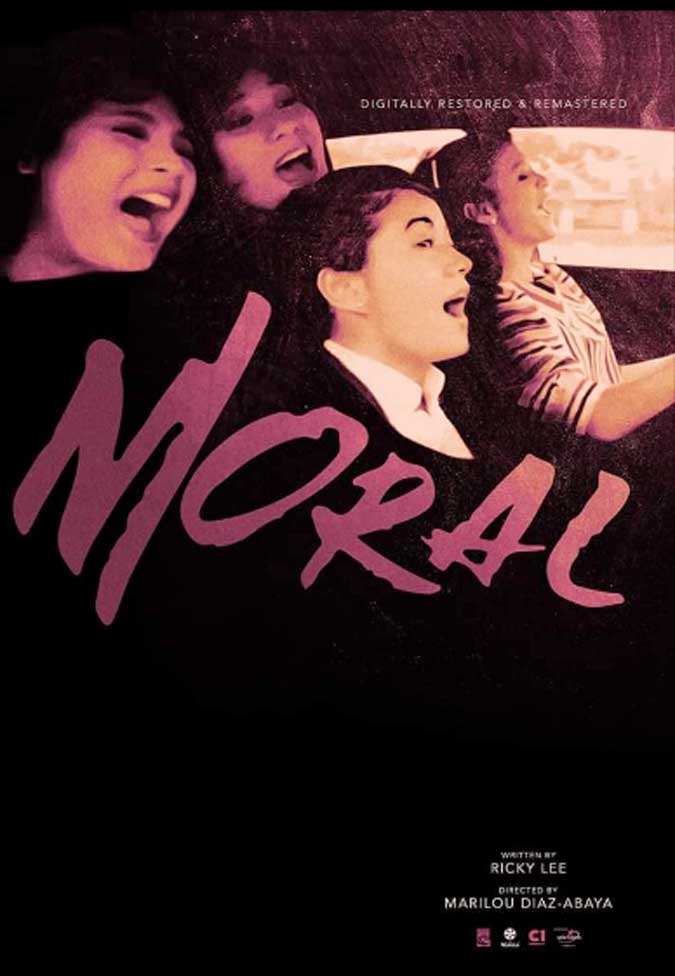

Moral

Directed by Marilou Diaz-Abaya

Available on iTunes and KTX.PH

(Warning: narrative and plot twists discussed in explicit detail)

MARILOU Diaz-Abaya’s Moral (1982) bends stereotypes right from the start, beginning where most comedies and love stories end: with a marriage. Maritess (Anna Marin) is in the process of being wedded to (welded to?) Dodo (Ronald Bregendahl) when Joey (Lorna Tolentino) stumbles late into the church, fumbles her way to a seat, giggles at inappropriate moments; Kathy (Gina Alajar) sings a song, a heartfelt performance but — isn’t she a touch off-key? When the ceremonies end it’s not bride and groom running out from under a shower of tossed rice but bride and friend and friend and friend — Maritess and Joey and Kathy and Sylvia (Sandy Andolong) linked arm to arm, camera retreating before them as they march forth into the world.

MARILOU Diaz-Abaya’s Moral (1982) bends stereotypes right from the start, beginning where most comedies and love stories end: with a marriage. Maritess (Anna Marin) is in the process of being wedded to (welded to?) Dodo (Ronald Bregendahl) when Joey (Lorna Tolentino) stumbles late into the church, fumbles her way to a seat, giggles at inappropriate moments; Kathy (Gina Alajar) sings a song, a heartfelt performance but — isn’t she a touch off-key? When the ceremonies end it’s not bride and groom running out from under a shower of tossed rice but bride and friend and friend and friend — Maritess and Joey and Kathy and Sylvia (Sandy Andolong) linked arm to arm, camera retreating before them as they march forth into the world.

We follow Maritess as she settles into the role of wife and mother in a large house (“it’s over 50 years old!”) and even larger family (children and infants crawling in and out of all corners). We learn about her friends — Kathy is an aspiring singer whose ambition outpaces her ability; Sylvia is an education major turned teacher (we see the four graduating from college) separated from her husband; Joey is the wild child that links the four. Joey can never tell where she’ll spend the night, in one of her friends’ spare bedrooms, at her mother’s, or with one of the many men she’s slept with.

Maritess chides Joey on her lifestyle: “Women aren’t supposed to be promiscuous, only men.” That I think is the key statement describing Joey: not that she’s a man with breasts and vagina attached but a woman who never really thought in those distinctions. Ironic twist: she does care about one man — political activist Jerry (Michael Sandico) who’s near-unattainable, committed to the idea of political commitment.

Ms. Diaz-Abaya is the director of this ensemble piece but it’s impossible to discuss the film without mentioning the rest of her ensemble, not just the actors (who are superb) but writer Ricky Lee. I’ve seen my share of Mr. Lee films, some which I’ve liked some which I, alas, haven’t; this may be his best work, and strong evidence to consider Mr. Lee a co-auteur. The writer-director team, coming off of the success of Brutal (one of Lee’s several reworkings of Kurosawa’s Rashomon), wanted to do a second film using the previous feature’s two stars, Gina Alajar and Amy Austria, involving a talented singer and a less talented one. But Austria left the production, and Mr. Lee reworked the script into a story of four friends.

The film’s form is an assumed formlessness but you can see the thinking that went into the script: Kathy’s story satirizes showbiz; Sylvia’s explores homosexuality; Maritess’ deals with the traditional role of women as selfless wife and mother. Joey, I suspect, represents Filipino feminism in the 1980s, a rebel in search for a cause — she’s just not sure what. That’s what attracts her to Jerry: he knows what he wants and is working passionately to achieve it.

That’s the agenda, and Mr. Lee and Ms. Diaz-Abaya work to fudge the outlines of that agenda, distract us from looking closely at the structure. The dialogue helps, the film featuring some of Lee’s funniest lines, including a discourse on underwear (“You can tell a man from the briefs he wears.”). You imagine Ms. Diaz-Abaya, like Fellini, taping a reminder to her camera: “remember this is a comedy.” Ms. Diaz-Abaya takes her cue from Joey as she jumps from one storyline to the next in apparent random order; she cuts (with help from husband Manolo Abaya and Marc Tarnate) with the no-nonsense air of a comic director keeping the pace brisk, the audience off-balanced. Mr. Lee further contributes by throwing the women curveballs: Jerry introduces Joey to his fiance Nita (Mia Gutierrez); Sylvia realizes her husband Robert (Juan Rodrigo) has a boyfriend Celso (Lito Pimentel) who dances in a nightclub; Kathy — well she’s in showbiz and showbiz is nothing but curveballs (that’s why industry folk are so paranoid); Maritess slowly realizes what kind of family she’s married into and what’s expected of her (she’s a factory worker expected to churn out babies).

Helps (again) that Lee’s curveballs themselves are sometimes fascinating. Mr. Pimentel’s Celso is a languid zen hedonist living in an airy apartment: tall grilled-iron windows draped with ribbony curtains, the naked concrete ornamented with carvings and Robert’s paintings; he serves Sylvia brewed coffee (this was before Starbuck’s aggressive worldwide expansion) and mentions a supplier in Batangas (he could almost be talking about quality cocaine). He insists that he and Robert are partners, suggesting a more enlightened arrangement than traditional marriage, though when he breaks down their respective duties — he does the shopping and cooking, Robert does the house repairs and pays the rent — you sense a more exploitative slant. Celso seems to consider himself a performing artist, and lives on his own terms (he loves Robert, but refuses to stay faithful); Sylvia looks on, appearing both enlightened and overwhelmed, and not a little envious.

Then there’s Joey’s mother Maggie (Laurice Guillen) who had been forced to give birth to Joey at 15 and left child and husband not much later. She’s had a tumultuous life to put it mildly and I don’t see anyone sending her a Happy Mother’s Day card anytime soon (for one she used to slap Joey for calling her “mother” instead of “Maggie”). Script and film seem to want to position her as a villain, but Ms. Guillen plays Maggie with defiant dignity; like Celso she may be morally questionable, but quietly insists on her right to exist.

I did mention Moral bends rather than breaks stereotypes; it has its predecessors in structure and subject matter, including Ishmael Bernal’s Aliw (1979) and Manila by Night (1980); Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers (1972); Kenji Mizoguchi’s Street of Shame (1956); even Gregory la Cava’s Stage Door (1937). What Ms. Diaz-Abaya and Mr. Lee add to a small but diverse library is a royal flush of performances, an understated comic sensibility, and the beautifully silvered yet naturalist glow of 1970s and early ‘80s Filipino cinema (brought about by, again, Manolo Abaya — there’s an argument to be made that he along with Mr. Lee and Ms. Diaz-Abaya are co-auteurs).

There’s predecessors and then there’s politics, and looking back almost 30 years later they seem surprisingly dated — surprising because we remember the film to be such a pioneering landmark. I’ve mentioned Maggie being set up as a villain (and submit Ms. Guillen’s performance mitigates that); Joey in turn is apparently punished for her promiscuity — she’s knocked up (doesn’t know by whom), goes around seeking money for an abortion. Maritess turns her down of course (“what you’re doing is wrong”); Maggie hems and haws (“you’ll only destroy your life”); Joey’s choice is ultimately taken from her — she has a miscarriage — and you wonder if Mr. Lee or Ms. Diaz-Abaya made the decision to unceremoniously pull the plug on that subplot. I’m thinking Ms. Diaz-Abaya — she has both progressive beliefs and a strong Catholic faith and the struggle between the two plays out continuously onscreen.

Take Maritess’ storyline: she’s in over her head, even to the point of sexual assault (she’d refused her husband sex); she leaves him, but in the end relents to seeing her husband to negotiate a more equitable relationship. I can see the point to her capitulation — there’s no divorce in the Philippines, legal separation is obtained with much difficulty, and marital rape was belatedly outlawed in 1997 — but would have liked to have seen more ambivalence, even some bitterness, in Ms. Marin’s performance.

With Gina Alajar’s Kathy, Mr. Lee and Ms. Diaz-Abaya are on more comfortable ground and go for comic gold. Kathy is hilariously clueless; every time she opens her mouth you cringe in anticipation. In an interview she articulates her new Hare Krishna/Catholic mishmash of a faith, responding to the journalist’s pointed questions: “some call me Kathy, some Katherine, still others Kate, and when I was young Tate; if I can have four names why can’t God?” Kathy does have a nicely played scene where she’s in bed with the single most corrupt figure she’s encountered so far (Jess Ramos’ corpulent Mr. Suarez) and asks: do I have talent? Things may be going her way but Kathy, after all is said and done, values truth over showbiz achievement, and the poignancy of the moment is made sharper by all the comedy that came before.

My favorite moment is possibly the conclusion to Joey’s storyline (if anyone’s the protagonist it’s likely her, the Portnoy of Filipino feminism, comically neurotic and sympathetically stubborn). When Jerry suddenly shows up and asks Joey to take in his newly pregnant wife while he joins the rebels, Joey accepts; she’s still that much in love. Joey’s short with Nita at first, but Nita fights back with modesty (“don’t mind me too much”) and an underhanded guilt-trip campaign (“Don’t bother with that! I have someone come in twice a week,” “That’s okay, it gives me something to do”). Joey comes home one day and Nita gets up to fix her supper; in the midst of preparation Nita drops the bomb: “Jerry’s dead.”

It’s a great scene and I suspect Mr. Lee’s (he had once been arrested and enjoyed the full hospitality of Marcos’ enhanced interrogation officers), but Ms. Diaz-Abaya stages the scene with matter-of-fact directness and husband Manolo lights and shoots it with beguiling simplicity. Nita continues to prepare supper, recounting with quiet dignity how Jerry was captured, tortured, killed, the white kitchen tiles suggesting her just-canonized status as both political activist and soon-to-be mother; Joey on the other hand sits on her bed in the opposite corner of the studio apartment, the shadows gathered around suggesting the depths of her despair. The scene is sad of course, but also horrifyingly funny: how can Joey possibly compete? Nita doesn’t just have Jerry’s love, she carries Jerry’s child and is getting ready (has her bag all packed) to continue Jerry’s legacy. Game set match: Joey is left with hugging Nita and her unborn child tight, the only possible way she can bid Jerry farewell.

What else can I say? Moral is flawed yes but fascinatingly so, borne I suspect from the director’s inner contradictions; it’s an ensemble film about an ensemble of friends and while not as radical as we remember it, is still a well-rendered example of the genre. Great film? Thought so, and watching this restored version I’m happy to say still do.