PHL stands at K-12 crossroads as learning crisis deepens

By Almira Louise S. Martinez, Reporter

As it falls short of delivering on its promise of producing employable graduates, the case for the K-to-12 program is further called into question amid the persistent learning crisis in the country.

No less than President Ferdinand R. Marcos, Jr. himself said in June that the program has failed to provide students with any real advantage, leaving it for lawmakers to decide whether its abolition is in order. Education experts, however, assert the program should stay.

“I will be the first to say it is not a perfect program, but it is a good program,” Armin B. Luistro, the former Department of Education (DepEd) secretary who oversaw the implementation of the K-12 program, told BusinessWorld in an interview.

The administration of former President Benigno S. Aquino III enacted the Universal Kindergarten law in 2012 as part of the phased implementation of the 13-year curriculum, followed by the enhanced K-12 program for Grades 1 to 7 in 2013. By 2014, the Senior High School (SHS) curriculum was finished and operationalized nationwide in 2016.

“The basic minimum requirement for K-12…, beginning in Kindergarten, was there,” Mr. Luistro said. “Were we 100% prepared? Obviously not, and we said that.”

“Obviously we were rushing it because this was the biggest reform in the educational system since the pre-American period,” Mr. Luistro said. “We needed to do it within the six-year period of a president.”

Mr. Luistro said its implementation was a “judgment call,” noting that changes in administration could disrupt long-term initiatives, such as the implementation of a new curriculum.

Before the K-12 implementation, the Philippines was the only country in Asia, and one of the three countries globally, with a 10-year pre-university cycle consisting of six elementary years and four years of high school.

The SHS component of the K-12 curriculum is designed to cover three exit points: higher education, middle-level skills development, and employment or entrepreneurship, according to the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS).

The additional two years to the 10-year curriculum was expected to produce graduates ready to enter employment and entrepreneurship — a major selling point of the program. PIDS, however, found that more than 70% of graduates prefer to pursue higher education rather than enter the labor market.

“Most students believed that employers consider educational qualifications, technical skills, soft skills, and attitude when hiring,” the study said. “They also expected to receive a minimum wage appropriate to their qualification as SHS graduates.”

The study added that among the roles commonly available to SHS graduates, such as bakery worker, barista, carpenter, cashier, encoder, clerk, online jobs, service crew, and welder, being a call center agent is the only one perceived to have better pay.

Data from the local statistics agency in April showed that unemployment among those aged 15 and above increased slightly to 2.06 million from 1.93 million in March 2025.

FLAWED CURRICULUM

The unemployment rate among SHS graduates is caused by a combination of structural and systemic issues, including job-skills mismatch, lack of decent and regular jobs, contractualization and outsourced labor schemes, employer bias, weak post-graduation support, and lack of coherent government planning, said Federation of Free Workers (FFW) President Jose Sonny G. Matula.

“Despite being theoretically ‘job-ready,’ SHS graduates are frequently passed over in favor of college-educated applicants,” Mr. Matula told BusinessWorld in a Viber message.

In a June 18 podcast, President Marcos raised the same concern, saying that while the curriculum that has added financial strain to families, it has yet to show its desired outcome.

To address the lack of career options for SHS graduates, Mr. Matula said students must not be treated as disposable labor. “They deserve decent work and a dignified future.”

Education Secretary Juan Edgardo “Sonny” M. Angara also highlighted the role the government has to play as the forerunner in hiring SHS graduates.

“The government has to set an example. It has to send a clear message,” Mr. Angara said during the launch of the Quality Basic Education Development Plan (QBEDP) 2025-2035.

The DepEd has said that the excessive number of subjects could be overwhelming for students, which hampers their focus and job readiness. Additionally, Alliance of Concerned Teachers (ACT) National Capital Region President Ruby Bernardo said that the K-12 curriculum is harder for students because it uses the Spiral Progression Approach and assumes students are “independent learners.”

“It was already assumed that students were proficient in reading, writing, and arithmetic once they entered school,” Ms. Bernardo said in an interview. “It does not hone critical and independent thinkers.”

She added that by focusing on the Key Stage 1 (KS1) or the foundational years, it could help improve the literacy and competency of learners.

Other academically high-performing countries, such as Singapore, also focused on strengthening students’ foundational years, said INNOTECH Centre Director Majah-Leah V. Ravago. “They have very few subjects that focus on the foundation, and so the students’ learning is very deep.”

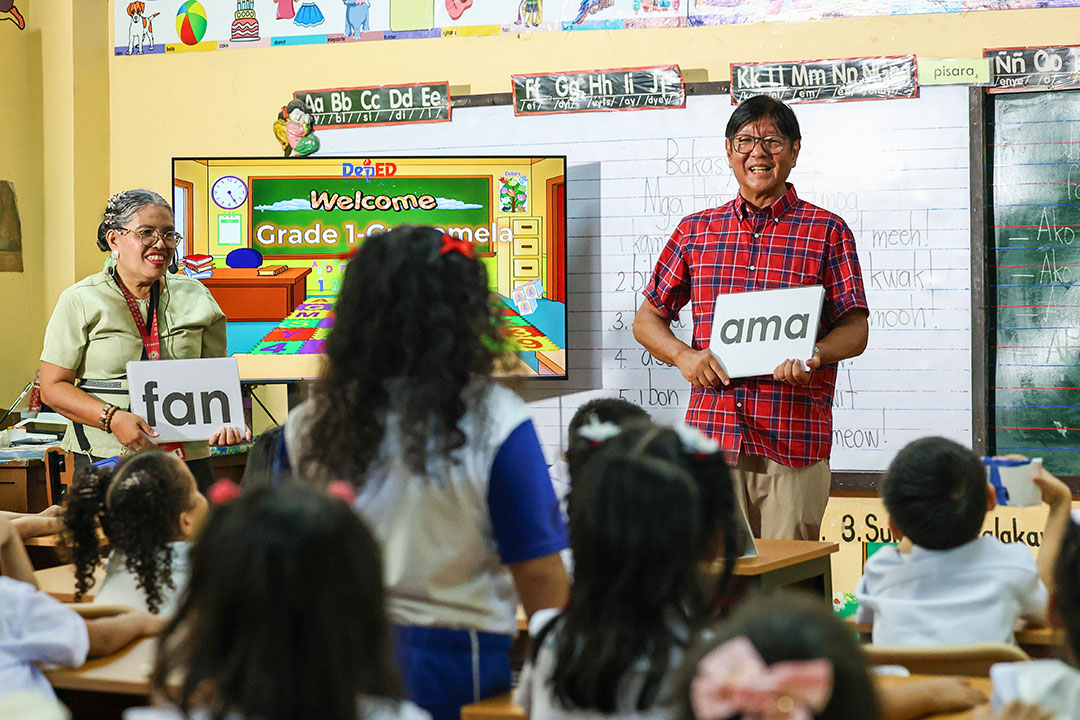

The department has started work on decongesting and recalibrating the program, through the MATATAG curriculum, the Philippines’ revised basic education curriculum, launched in 2023. The reform aims to strengthen the foundational skills of students, particularly in language, literacy, mathematics, nationalism, and good manners and right conduct.

The first phase of the MATATAG curriculum was rolled out in school year (SY) 2024-2025 for Kindergarten, Grade 1, Grade 4, and Grade 7. Meanwhile, the implementation for Grades 2, 3, 5, and 8 began this school year.

Aside from MATATAG, the pilot implementation of the strengthened SHS curriculum in over 900 schools nationwide also started this school year. Under the revised program, core subjects in Grade 11 were reduced to only five from 15 per semester. Tracks were also reduced to Academic and Technical Professional (TechPro). Grades 11 and 12 students were also allowed to select their elective subjects regardless of their chosen track.

Despite these initiatives, some critics have petitioned reverting to the 10-year basic education cycle to alleviate the financial burden and address the poor learning outcomes associated with the current curriculum.

Among them is Senate President Pro Tempore Jose “Jinggoy” Ejercito Estrada, who refiled his proposal to remove Grades 11 and 12, under Senate Bill No. 72, the Rationalized Basic Education Act. At the House of Representatives, Leyte Rep. Richard I. Gomez filed House Bill No. 374, proposing to repeal Republic Act No. 10533, the Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013.

Former DepEd Secretary Luistro, however, asserted that an infrastructure like the K-12 will always have flaws and weak points — whether it’s in the curriculum itself, teachers, or in the implementation.

“There are gaps when we started, there are gaps now, and there will still be gaps in the future,” Mr. Luistro said.

“The 10-year program was not working either,” he added. “Is the K-12 better? Well, at least this is a global standard.”

Removing the SHS curriculum could also jeopardize the Philippine Qualification Framework (PQF), which aligns the country with member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), an analyst said.

PQF, aligned with the ASEAN Qualifications Reference Framework (AQRF), standardizes the levels of educational qualifications and learning achievements in the country. It supports policy and planning formulation by comparing qualification frameworks with other ASEAN countries, which in turn fosters mutual recognition arrangements between the nations.

“In that framework, it states that our basic education should be K-to-12,” University of the Philippines Diliman (UPD) College of Education Dean Joel C. Javiniar said in Filipino. “So if we were to remove Grades 11 and 12, what would happen to the Philippine Qualifications Framework?”

“Are we going to turn our backs on our agreements with ASEAN?” he added.

BEYOND CURRICULUM

Critics have linked the gaps in the curriculum to the poor performance of Filipino students in international assessments, which exposed just how severe the learning crisis is in the Philippines.

Filipino students were among the world’s weakest in math, reading, and science, according to the 2022 Programme for International Student Assessment. The country also ranked 77th out of 81 countries and performed worse than the global average in all categories.

But, while it is easy to blame the curriculum, Ms. Ravago told BusinessWorld in an interview that the problem goes beyond the K-12 program.

“There is also the function of resources, the budget being put into the education, and with that it’s also preconditioned on the capacity to spend,” she said.

A report by the Second Congressional Commission on Education (EDCOM II) in January said that the budget for the education sector still fails to meet the demands for global standards. EDCOM stated that the Philippines allocated an average of 3.2%, lower than the recommended 4% to 6%, of its gross domestic product (GDP) to education.

Ms. Ravago also factored in the function of teachers and leadership, and the overall challenge posed by the pandemic.

“You cannot attribute the low learning outcomes solely to K-to-12,” she said.