Creating an impenetrable shield against disorder

By Bjorn Biel M. Beltran, Special Features and Content Assistant Editor

“For an impenetrable shield, stand inside yourself.”

Henry David Thoreau, the most commonly attributed source of that quote, posited that with inner strength and unshakeable fortitude, one can overcome almost anything. The most powerful defense is internal.

This universal truth was reached by the final panel of BusinessWorld Forecast 2026, where representatives from trade organizations and think tanks came together to discuss “Navigating New Normal in Trade: How Philippines Is Faring in the New Global Trade Order.”

Since recovering from the global pandemic, international trade has been defined less by recovery and more by turbulence. Geopolitics is now a disruptive force of its own, reshaping value chains and redrawing the map of opportunity. Major economies like the United States under President Donald Trump are forcing supply chains to recalibrate, even as technology becomes ever necessary through the proliferation of digital systems and economies. This shifting order has sharpened competition across Asia and exposed long-standing vulnerabilities in trade-dependent economies like the Philippines.

“Today the world, I would say, is in a global disorder,” Stratbase Institute President Victor Andres “Dindo” C. Manhit said.

Since the Second World War, Mr. Manhit explained, there had been a prevailing narrative about the world: that the West had been up to now the custodians of the global order, and that the Philippines as a country has benefitted greatly from this order. But as Western influence wanes, those who have questioned that arrangement — countries like China, Russia, and Iran — are stepping into the limelight.

“The past few years we have seen a confluence of national security and economic security,” he said. “I see a world whereby the Philippines is in the middle.”

The Philippines, as he sees it, is in the perfect strategic position to take advantage of shifting geopolitics. However, the country cannot rely on external momentum alone. It needs its own foundation, and that is the greatest challenge.

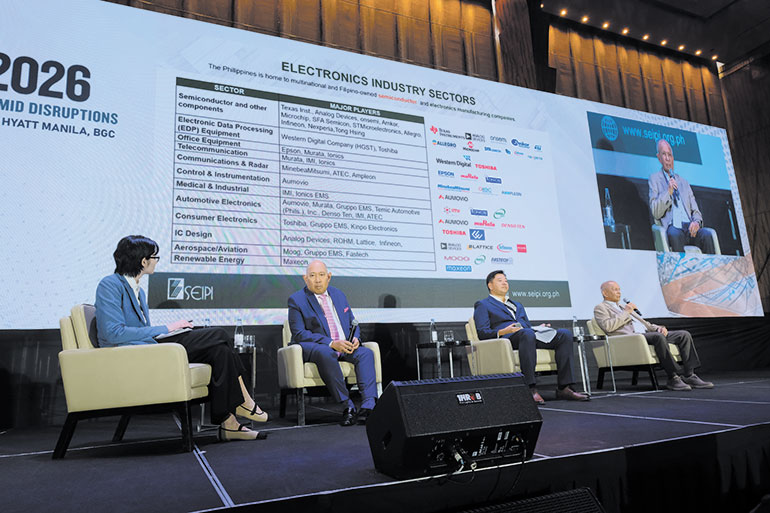

No industry illustrates the tension better than electronics. The sector has long been the backbone of Philippine exports. Semiconductor and Electronics Industries in the Philippines Foundation, Inc. President Danilo “Dan” C. Lachica laid out the magnitude with precision.

“The sector accounts for 70% of the country’s $42.6-billion exports,” he said, noting that despite earlier projections of flat growth due to inventory corrections and reciprocal tariffs, the industry is still seeing growth riding the wave of advanced technologies. “Because of artificial intelligence, data centers, TVs, and all that, we’re now looking at 5% to 7% growth.”

Yet, the very success of electronics exposes how narrow the country’s export base has become. Mr. Lachica was quick to point out the structural fragility: global electronics supply chains flow overwhelmingly through Hong Kong, and China still is the biggest export origin.

During the pandemic, this near-total dependence locked the industry into paralysis. “We were practically at a standstill,” he recalled.

Even now, the sector’s integration into global technological trends is not matched by equally strong domestic supply-chain development or industrial strategy. Mr. Lachica noted with concern that semiconductor electronics was absent from the initial priority track for ASEAN discussions in 2026 — despite being the country’s largest dollar generator. It’s a telling omission, and one that underscores how the Philippines still enjoys export success without fully anchoring it in national policy.

The rest of manufacturing illustrates this internal weakness. Federation of Philippine Industries President John Reinier H. Dizon reminded the audience how liberalization reshaped the country’s economic terrain.

“There are pros and cons of such free trade. There is nothing wrong with it,” he said. “But many other countries have placed more safeguards… The Philippines was maybe a little bit more aggressive. And as a consequence, over time, it actually affected our trade deficit.”

The consequences are visible across decades. “Several industries actually faltered,” Mr. Dizon said, citing the collapse of the Marikina shoe sector, the decline of textiles, and the fall of National Steel Corp. The country embraced free trade before building the productive base that would allow it to benefit from openness. Consumption rose, but the industrial core thinned.

The result today is a staggering trade imbalance. “We have the biggest trade deficit in ASEAN… about $54 billion,” he pointed out. “If we compare that with the likes of Vietnam, they actually had a trade surplus of $28 billion. Thailand, trade surplus of $6 billion. Malaysia, trade surplus of $20 billion. Indonesia, their trade deficits at a much more manageable level, at $15 billion.”

Thus, in the global market, the Philippines has become a consumer with relatively little to offer. So, how can a country leverage regional agreements or global markets if it has nothing to sell?

Mr. Dizon urged the government to put more effort into reviving manufacturing and production to support local industries. Initiatives like the Tatak Pinoy Act, or Republic Act No. 11981, aimed at enhancing collaboration between the government and private sector, is a start.

The shield we have yet to build

This foundational core begins with perception.

The Philippines, Mr. Manhit argued, needs to stop seeing itself as an accessory to bigger, more powerful countries. This shift in self-perception matters not just for diplomacy but for investment strategy. After six years of Chinese-focused foreign policy under the Duterte administration, he pointed out that the Philippines scarcely got any investment from Beijing. Real capital inflows continue to come from Japan, the United States, and the European Union, partners that coincidentally also align with the country’s security interests.

“Maybe it’s time for us to look at who our friends are and really build a secure economy that also protects our interests,” he said. “At the end of the day, we are in a good strategic position. Let’s maximize it.”

This convergence of geopolitics and economics may define the coming decade. Supply chain diversification, reshoring, and allied manufacturing give the Philippines the chance to reposition itself, but only if it stabilizes its policy environment and strengthens governance. Transparency, stable policies, and partnerships between the public and private sectors are now essential conditions for competitiveness.

For an impenetrable shield, one must create it inward. Competitiveness — one that can thrive in any storm — does not come from aligning with the right partners alone, nor from riding the growth of a single sector. It comes from building resilience within, through strong industries, governance, and institutions.

“Let’s stop looking at ourselves like such poor Filipinos,” Mr. Manhit encouraged. “Strategic thinkers used to say, ‘Why do you call yourself a small country? Because you’re not.’”

“We have the economy growing. We have a population that is big. We also need to think big,” he added.