Understanding Philippine corruption and government finances

By Jesus Felipe and Gerardo Largoza

The hundreds of billions of pesos that were stolen from flood control projects have robbed the Philippine economy of protection and productivity. But to say, as many Filipinos do, that they have been robbed of their taxes betrays a misunderstanding of how government finances actually work. Correcting such misconceptions is crucial because Philippine development has been held back by decades of public underinvestment and self-imposed austerity, possibly even more than it has by decades of corruption.

People are spilling onto major streets and gathering around public monuments to protest corruption scandals. This time it’s about flood control. President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. first dropped hints as to the scale of malversation in his State of the Nation Address last July. Since then, events have taken on a life of their own. After three months of Senate hearings, the public has been able to confirm what it has long suspected: hundreds of billions of pesos salted away from thousands of overpriced, substandard, or nonexistent (“ghost”) projects. Nearly every level of government has been implicated, from district engineers to managers of government banks, to mayors, provincial governors, members of Congress, senators, including the Speaker of the House who has had to step down.

Estimates on the extent of graft in flood control vary; at present, official figures range from P42 billion ($715 million) to P118.5 billion ($2 billion) misappropriated since 2023, according to the Department of Finance. Greenpeace extrapolates a much larger figure of P1.089 trillion ($18.5 billion) over the same period, based on the total allocation for “climate-tagged” expenditures, with P560 billion ($9.5 billion) lost to corruption in 2025 alone.

If it’s true that over a trillion pesos have been plundered since 2023 (and more dating back to 2016), then why hasn’t the Philippine economy collapsed the way it did in 1983 when President Ferdinand Marcos, Sr. and his cronies set the Guinness World Record for “largest ever theft from a government”?

To explain why some episodes of corruption destabilize economies while others don’t, we make two claims about how monetary systems work.

First, is that governments spend fiat money (their own currency) by crediting bank accounts. This creates money into the system. Governments do this through their banker, namely the central bank (the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas or BSP in the Philippines). This means that a government that issues its own currency cannot run out of money, because it can always create more by crediting bank accounts. It implies that corruption denominated in the local currency (today’s) is not the same as corruption denominated in foreign exchange (like the 1980s episode).

Second, and a consequence of the previous point, taxes do not finance government spending. In standard economics and public discourse, taxes are viewed as the way governments collect money from citizens to fund spending. According to this view, citizens pay taxes, money goes into the Treasury, the government uses that money to pay for roads, schools, etc. If taxes are insufficient, the government must borrow, usually by issuing bonds. In short, taxes fund spending. This is what most people, including government officials and many economists (!), believe. This, however, is not how modern economies, including the Philippines, function.

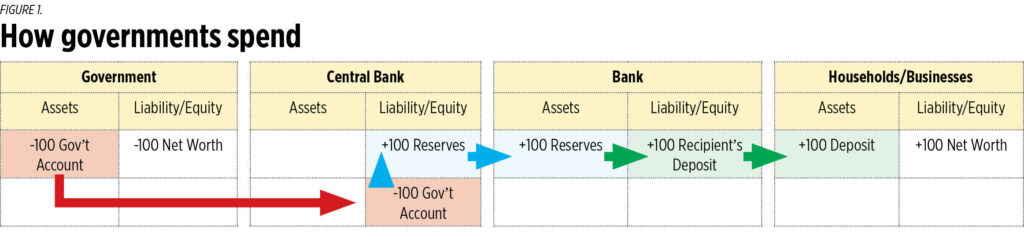

Operationally speaking, government spending comes first — that is, the government must spend money in the economy before it can collect it back as taxes. It is government spending that creates the money (in the form of so-called “reserve balances”) that people then use to pay taxes. Governments do not need to “get” money from the private sector to be able to spend. They simply need the political authority and institutional coordination to do so. In the Philippines, government accesses its account at the BSP and this creates “reserve balances,” an accounting annotation on the government’s account at BSP. These are then transferred to the commercial bank where the recipient (household or firm) has the account (through Land Bank of the Philippines). Government spending is a transfer to the private sector. Taxes are not involved. This is shown in Figure 1. This is the process for every single payment the government makes.

Taxes do not fund spending the way a household’s earnings fund grocery purchases because households do not create money. Governments do. Instead, the state’s power to tax is what gives the local currency its value and demand, since people need the currency to pay taxes. When a sovereign government spends, it credits bank accounts electronically — essentially creating new money, as spending adds reserves to the banking system. When it taxes, on the other hand, it deletes or removes money from the system; that is, taxes subtract from reserves.

Put another way, when Filipinos pay taxes, they instruct their banks to transfer some of their deposits (claims on reserves) to the Treasury’s account at the BSP. The BSP then reduces the amount of reserves in the banking system by that amount. Tax payments are ultimately settled by a transfer from the bank to BSP, which then credited the government’s account at BSP. Important: your bank needs to settle your tax payment with the government through its account at BSP. The government’s tax receipts are merely an accounting record — the money does not go into some kind of jar, earmarked for building roads, schools and ports. Instead, the funds are, in essence, deleted from the system; that is, the reserves are extinguished. So, taxes, in fact, destroy money, i.e., they remove money from circulation. This is shown in Figure 2. There is no operational procedure through which the National Government uses tax receipts or borrowing for its spending. Taxing and spending are operationally independent procedures.

The fact that taxes do not fund government spending for public goods does not make them useless. Taxes help manage demand (they take away private sector purchasing power), and they penalize “bads” such as smoking.

Why does this matter at a time when the burning question is how to swiftly bring grafters to justice? Because ideas have consequences. We insist that widespread corruption is a disgrace to the Philippines. The nation does not have the public goods that it needs. Filipinos have a real opportunity today to understand that the government has always had much more scope to spend pesos to build infrastructure and to provide public education and health. Yes, the culprits got away with the purchase of million-peso luxuries and Parisian apartments, and must be caught. Yet, they did not steal taxes from the Filipino people because it is technically impossible to steal taxes, and because pesos, properly conceived, are not a scarce resource. What did they steal? Reserve balances created by BSP. This may sound strange to many but it is the reality.

Correcting such misconceptions is crucial because Philippine development has been held back by decades of public underinvestment and self-imposed austerity, possibly even more than it has by decades of corruption.

We end with an invitation: if anyone with knowledge of the actual government and BSP payment system disagrees with this account (obviously we have shortened the process), let us know.

A longer version of this article can be downloaded from here: https://tinyurl.com/2cxgr237

Jesus Felipe is a distinguished professor of Economics, De La Salle University (Manila, Philippines). Gerardo Largoza is an associate professor of Economics at the same university.