Signs and Wonders

By Diwa C. Guinigundo

Keeping our external payments position stable is one of the key factors that the last week’s Fitch credit rating report identified as a strong point, a good pillar of sustainable economic growth. The premise of course is that the vital reforms will continue to make a positive dent on both the overall balance of payments position and our reduced propensity to borrow from the global capital markets.

Fair enough for Fitch to also zero in on the need to constantly improve external debt metrics relative to our gross domestic product (GDP) as a rating sensitivity. This means that if we succeed in keeping our external debt sustainable, together with parallel macroeconomic improvements, good public finance management, and better, not just good, governance, the likelihood of a positive, rather than merely stable, outlook, is higher. This could ultimately lead to a credit rating upgrade to BBB+ or even A-.

Can the Philippines deliver on this one important credit watch target?

We have a long, painful history of having to incur enormous external debt, the Philippines being a developing then an emerging economy. Our domestic savings are significantly less than our requirements for investment and growth. Either we tax our people dry or borrow from the capital markets and face a formidable debt servicing challenge. We learned our lessons, and they are still fresh, and we need to continue learning from such lessons of history.

We have a long, painful history of having to incur enormous external debt, the Philippines being a developing then an emerging economy. Our domestic savings are significantly less than our requirements for investment and growth. Either we tax our people dry or borrow from the capital markets and face a formidable debt servicing challenge. We learned our lessons, and they are still fresh, and we need to continue learning from such lessons of history.

It should still be fresh in the minds of the Baby Boomers among us that in 1960s, due to the post-war reconstruction efforts, expansionary fiscal and monetary policy was imperative to accommodate higher capital spending on infrastructure to accelerate growth. As a result, we accumulated a large volume of foreign debt that led to Congress passing RA 4860 or the Foreign Borrowings Act on Aug. 8, 1966 for regulatory purposes. Foreign borrowing was an easier option than to shepherd tax bills through two houses of Congress and convince civil society of its merit.

Thus, in the 1970s, the public sector continued to bloat while the private sector incurred more foreign loans following the balance of payments crisis in the latter part of the 1960s. Debt service ratios peaked at 30% although they moderated towards the 1980s.

External debt transformed into a virtually existential issue in the 1980s when oil prices hit the sky in the previous decade and oil companies demanded accelerated payments on oil imports. Counter-cyclical measures were put in place to encourage public investment programs, including putting up better banking infrastructure for more effective capture of OFW incomes, and tightening the foreign loan monitoring system. But the balance of payments (BOP) crisis following the weakening of external trade and reduction of external credit lines forced the Philippines to declare a 90-day moratorium, on Oct. 17, 1983, on the payments of the then $25-billion total foreign debt, followed by debt restructuring from 1983 to 1992.

In the 1990s, after a temporary decline in external debt, natural and man-made disasters triggered another round of escalation of foreign debt including a major earthquake in 1990, the Mt. Pinatubo eruption in 1991, and the electric power crisis in the first few years of the decade. While the IMF-supported adjustment program helped rationalize our external debt in the early 1990s, the Asian Financial Crisis starting 1997 pushed external debt higher.

Of recent memory, in the 2000s, we had the Great Financial Crisis and the European Debt Crisis. The last 20 years saw the rapid increase of foreign borrowings attributed to both public and private sector debtors, as well as the significant FX revaluation with the strengthening of the Japanese yen against the US dollar. More than half was public sector debt while maturities were skewed toward the long-term.

It was only during the last 20 years that the Philippines managed to lengthen its maturity structure and sustain its robust economic growth and improving external payments position. In fact, we managed to prepay our debt obligations with the IMF in December 2006 and exit it after 44 years of sustained borrowings. In fact, both the government and some corporate borrowers continued to prepay their foreign loans through most of the 2000s. Good growth performance and a stable peso allowed this debt breakthrough that made the Philippines a creditor to the IMF until today.

It was only during the last 20 years that the Philippines managed to lengthen its maturity structure and sustain its robust economic growth and improving external payments position. In fact, we managed to prepay our debt obligations with the IMF in December 2006 and exit it after 44 years of sustained borrowings. In fact, both the government and some corporate borrowers continued to prepay their foreign loans through most of the 2000s. Good growth performance and a stable peso allowed this debt breakthrough that made the Philippines a creditor to the IMF until today.

One embarrassing outcome in the past of being highly indebted in this part of the world, where most of our neighbors had better external debt metrics, is that we were often associated with our Latin American friends like Argentina and Mexico.

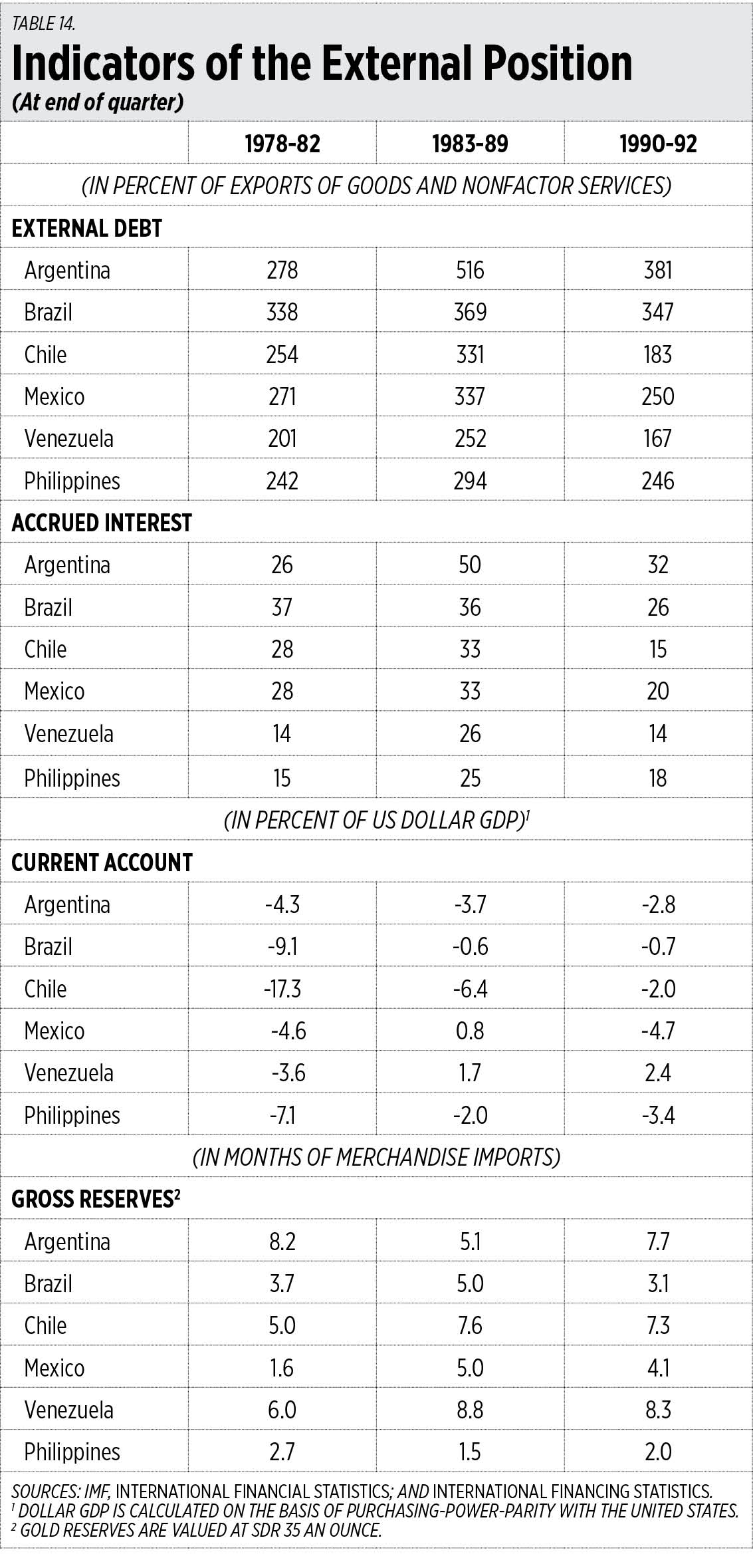

The Philippines was one of six heavily indebted countries in this list, together with Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Venezuela. While our public and private borrowings as a percent of GDP were mostly comparable, our foreign investment and other flows paled in comparison during certain periods. In short, while we borrowed increasingly for both public and private sectors, the compensatory inflows of foreign investment and other flows were not growing enough to lessen our reliance on foreign borrowings.

In the 1970s and 1980s, our external debt level was high relative to our exports of goods and non-factor services. The same applied to accrued interest. Our current account deficit was high relative to our GDP in dollars while our FX reserves were rather low in terms of import cover. There was very little in the quality of our debt ratios while our current account somehow improved, with better merchandise trade and OFW remittances providing a better ratio to our GDP. Reserve cover continued to be far from comfortable up to the 1990s.

How did the Philippines turn the corner?

To begin with, it was a wise idea that external debt management be handled by the central bank. By law, many central banks are autonomous and independent. Therefore, they can be perceived as a good referee of external debt statistics and management in terms of data and policy integrity.

In the Philippines, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) is empowered in its charter to keep debt data and regulate the country’s external debt covering both public and private sector credits. Debt statistics are compiled consistent with international best practices and data standards.

The BSP’s role in ensuring external debt sustainability is closely related to its primary mandate of maintaining price stability and promoting the international convertibility of the Philippine peso. The BSP implements this mandate by ensuring that proper answers to three conditions are addressed: knowing one’s debt, deciding how much to borrow, and deciding how to fund the financing gap. It has the appropriate mechanisms to determine the borrowing requirements of the economy and the protocols to ensure that none of the terms of borrowings could compromise the country’s debt servicing capacity.

The point is to ensure that the country is not trapped in debt servicing difficulties. To augment domestic savings, it is best to set a pecking order: grants and foreign loans on concessional terms would be first best. Loans from foreign banks could be quicker and more flexible — key considerations would be to get the highest grant element, minimum market finance, maximum rollover financing feature, and minimum debt repayments for the next five years. Exchange rate fluctuations should also be considered to avoid FX risk and debt servicing difficulty.

What had been the results at least prior to the COVID-19 pandemic?

As the Philippine economy transitioned into a more resilient economy after its restructuring experience in the 1980s, and key policy and structural reforms were put in place, its external debt burden, while growing steadily, has gone down relative to GDP. This is a classic case of outgrowing our debt — not only by positive economic performance but also by judicious external debt management.

These two pillars are what we need today.

While total outstanding external debt continued to expand as the needs of the economy for capital grew, the country’s total output also rose significantly over the years since the BOP and debt crises of the 1980s.

At the same time, with diligent external debt management, two major external debt sustainability measures have improved significantly over the years.

The external debt to GDP ratio, as a measure of solvency, has gone down from 75.5% in 1985, to 57.3% in 2005, and down to 28.7% in 2023.

The gross international reserves (GIR) coverage ratio in terms of imports of goods and services has also perked up sharply: 38.4% in 1985, up to 246.6% in 2005, and up to 703.3% in 2023. This means improved liquidity.

If we go by the key debt metrics in the Philippines compared to 20 and 40 years ago, we should be capable of sustaining this trend over the long haul.

Indeed, we had thought, and thought wrongly, that the rolling years with debt-financed growth would never end; it was easy to finance growth. But the hefty increase in oil prices and decline in commodity prices were wake-up calls to us. It was good we managed to institute policy reforms and gained economic resiliency.

Debt is indeed like any other trap, easy to get into, but hard to get out of. Yet good governance will allow us to consider other options like tough reforms in the fiscal arena, in infrastructure, and in agriculture, as well as diligent external debt management. This is how we can avoid a repeat of the past.

Diwa C. Guinigundo is the former deputy governor for the Monetary and Economics Sector, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP). He served the BSP for 41 years. In 2001-2003, he was alternate executive director at the International Monetary Fund in Washington, DC. He is the senior pastor of the Fullness of Christ International Ministries in Mandaluyong.