By Romeo L. Bernardo

(I am pleased to share with readers a post to subscribers of Globalsource Partners (globalsourcepartners.com) written by Christine Tang and I.)

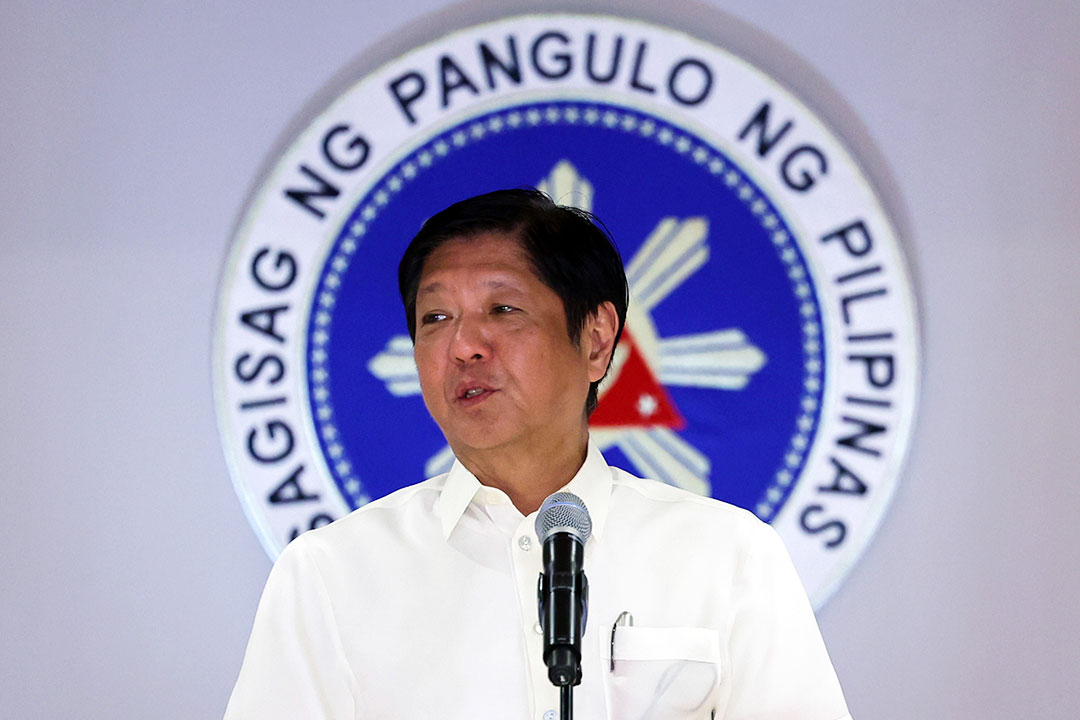

WHEN Ferdinand R. Marcos, Jr. assumed power at the end of June last year, we listed five areas where the new administration needed to take fire-fighting stances to speed up post-pandemic recovery. These were: a.) battling inflation and putting fiscal consolidation on more solid footing to ensure macroeconomic stability, b.) rebuilding private sector trust in long-term public-private partnership (PPP) contracts to expand financing sources for infrastructure, c.) addressing high food prices which the President drew attention to by appointing himself agriculture secretary, d.) crafting an exit plan for COVID-19 to allow the economy to fully reopen and start addressing the pandemic’s scars especially on education and worker skills, and, e.) addressing uncertainties in the power sector affecting the reliability and cost of electric power over the medium-term.

YEAR 1 PERFORMANCE IN BRIEF

There were hits and misses. Where the administration got it right from the start was to abandon lockdown as a policy to control COVID. This unleashed unexpectedly large pent-up demand quickly that pushed last year’s GDP growth past most forecasts. Where it most evidently got it wrong was in managing food supplies. Skyrocketing prices of items that make up a tiny part of the consumer’s food basket (notably sugar and onions) generated outsized impacts on inflation at a time of already elevated global food and energy prices. Alongside a recovering economy, tight global financial conditions, and volatile financial markets, it left monetary authorities with no choice but to raise interest rates aggressively and saw agriculture officials resorting to stopgaps in the form of food subsidies through a network of (Kadiwa) retail stores/pop-ups/on-wheels outlets.

The administration may also be credited for the steps taken to build on the foreign investment liberalization laws left behind by the previous administration. These included the issuance of the implementing rules and regulations (IRR) of the Public Services Act and re-writing of the same for the BOT law, the Senate’s ratification of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and greater regulatory clarity with respect to investments in renewable energy. It also caught the eye of foreign policy experts by moving further away from an overly pro-China stance whilst trying to avoid antagonizing the neighborhood giant. The foreign trips of the President to major industrialized countries, accompanied by his economic team and business leaders, doubly served as roadshows to showcase the Philippines as an investment destination.

One year on, positive reviews on the administration’s performance from business circles [show] appreciation that President Marcos has exhibited none of his father’s autocratic qualities, nor of his predecessor’s uncivility, boorishness. He has been praised for choosing high caliber cabinet members, including his latest cabinet appointments for the health and defense departments as well as the governorship of the BSP. His personal more consultative style vis-à-vis the business sector has also been welcomed. At the same time, criticism against the administration in the economic area included: failures to take necessary decisions in a timely manner, most notably in agriculture, the President’s purview, that led to shortages of certain basic food items and thus, high prices; seeming haste to act on ideas that have not benefited from complete staff work as in the case of the Maharlika fund; and, insufficient consultation with stakeholders on otherwise good reforms as in the case of the military pension reform which entailed unnecessary losses in political capital.

YEAR 2 CONTEXT

Entering its second year, the Marcos administration continues to face strong external headwinds with economic growth of key trade partners (US, Japan, China) predicted to slow further in 2024, persistence of inflation in advanced economies that is expected to lead to more policy interest rate hikes and possible spillover effects from US financial sector stress, and continuing geopolitical tensions raising uncertainties all around, from food and energy prices to trade, technology, and regional security risks.

Domestically, pent-up demand is easing and macro policy room, monetary and fiscal, remains limited. While government is committed to its 5% of GDP infrastructure spending target, it has yet to line up adequate revenue generating tax reforms to be able to, at the same time, stick to its medium-term fiscal consolidation program. Too, despite several international roadshows declaring the Philippines open for business, foreign investment inflows are still in trickles with the total for the first four months of this year almost 20% lower than last year’s, amidst feedback of poor follow through domestically by bureaucrats when the investors come to look see.

THE NEXT 365 DAYS

The President’s economic managers are eyeing more investments to enable the economy to reach an accelerated GDP growth rate of 6.5% to 8% over the medium-term and provide better local jobs. Current global economic conditions may not be on the administration’s side but a lot of work is still pending to increase the odds of translating all the marketing efforts into actual investments in brick-and-mortar and/or e-commerce businesses. Below are some of the priorities we see:

1. In line with the practice in private companies, government’s Medium-term Philippine Development Plan (MTPDP) needs an accompanying action plan that concretely spells out shorter-term strategies, resource constraints, refined timelines and persons accountable for the deliverables. This will help in identifying gaps and bottlenecks and additional resources needed, whether public or private. At the macro level, a more exhaustive revenue/tax program is needed to anchor medium-term fiscal targets. At the program level, the Maharlika Fund, which is not in the MTPDP but has been identified as a priority measure and signed into law this week, needs detailed mapping out to ensure that as a vehicle for bringing in private investments in strategic sectors, it will not be a source of unmanageable fiscal risks down the road. Job one, finding credible highly regarded fund manager CEO and board directors, will not be easy, given the ambitious return and development objectives that its sponsors have publicized. They also need to find an institution builder that will define the rules, risk management principles, investment guidelines, and other governance guardrails of this new agency. It’s actually better if this is done separate from the investment mindset, so such guardrails are shorn of agendas and biases.

2. Following its welcoming stance for public-private partnerships (PPP) in infrastructure, government now needs to identify low-hanging fruits, expedite approvals from national to local levels, and get the program up and running to attract even more investments. Among the issues that government needs to demonstrate progress include clearing right of ways, automatic fare adjustments per formula, and, not the least, addressing inordinate delays in all legs of the multilevel, multi-agency, and in some cases multi-year preparation, evaluation, and approval process. The PPP center will need to play its proper role, not just in promoting but in facilitating. Local government units also need capacity building for preparing PPP projects to be able to tap private finance for local projects.

3. We said many times last year that one of the President’s most pressing tasks is to find a suitable agriculture secretary, one who not only understands the sector but is honest and bold to take on powerful vested interests and perhaps most importantly, has the President’s ear. Although we still think this ideal, it appears that nobody has the necessary skills mix for the job or in any case, nobody suitable wants the job. Following the proposal of a sector expert, perhaps finding a highly technically capable senior undersecretary who could serve as the President’s alter-ego may be the second-best option.

4. He also needs to address food security both in the short term (driven by geopolitical events like Russia’s termination of the deal allowing Ukraine to ship out wheat) and long-term (climate change) by allowing more food imports and enabling the private sector to be more resilient in responding to food shortages.

5. With the country now facing a likely two gap (fiscal and foreign exchange) scenario over the medium term, and BPOs now running into headwinds due to talent constraint, and, down the road, potentially disruptive regenerative AI, the country needs to find new growth and foreign exchange sources. Mining and tourism have been identified, but the administration needs new policies to drive their growth.

All told, we would agree with conclusion of Ramos Finance Secretary Roberto De Ocampo, OBE, in a recent column that “it would seem that the pluses have outweighed the minuses so far and the private sector’s wait-and-see posture is leaning more toward a qualified but positive assessment” (“Crossroads,” PDI, June 22, 2023).

Romeo L. Bernardo is principal Philippine adviser to GlobalSource Partners (globalsourcepartners.com). He serves as a board director in leading companies in banking and financial services, telecommunication, energy, food and beverage, education, real estate, and others. He has had a 20-year run in the public sector, including stints in the Department of Finance (Undersecretary), the IMF, World Bank, and the ADB.

romeo.lopez.bernardo@gmail.com