Can CITIRA help revive the economy in the middle of this COVID-19 crisis?

It is disquieting to read a news report about Senate President Tito Sotto promising to fast track the passage of CITIRA (Corporate Income Tax and Incentive Reform Act) by the Senate, justifying it as an urgent measure needed to stimulate the economy. All agree that the economy needs to recover as fast as it can. It was already reported in the first quarter of this year that on a year-to-year basis, the GDP contracted by 0.2%.

In the middle of this crisis, it is likely that CITIRA can drive away existing investors and reduce the country’s exports, without the offsetting gain of higher tax revenues and new investments.

CITIRA has two parts. One is lowering the corporate income tax from 30% to 20% in 10 years, the other to rationalize the country’s investment incentives to make them “

Since the 1990s, we have had two reductions of the corporate tax, in 1997 and 2009. Both reforms were taken to stimulate the economy. In 1997, the region was hit by the Asian financial crisis and its economies contracted or their growth slowed. The corporate tax was reduced from 35% to 32% over a three-year period, part of the comprehensive tax reform program (CTRP) of 1997. The second cut happened in 2009, and followed the global financial and economic crisis in 2008. Our Congress cut the rate from 32% to 30% then.

The CTRP was like the current tax reform program of the current government. The reforms covered income taxes including personal income tax, and the excise tax on alcohol and cigarettes. It failed in preventing the rise of the marginal tax rates on personal income tax brackets by not including inflation adjustments to personal income tax brackets. While it was touted to minimize revenue leakages, it did not succeed so in excise taxes on cigarettes, with specific tax rates and multi-tier rates that allowed producers to legally avoid their tax dues, resulting in the decline of excise tax revenues.

CITIRA forms an important phase of this government’s tax reform program. It is designed to increase investments and promote economic growth, which Senate President Sotto stressed as urgently needed to reverse the decline of the economy due to the national government’s COVID-related quarantine regulations.

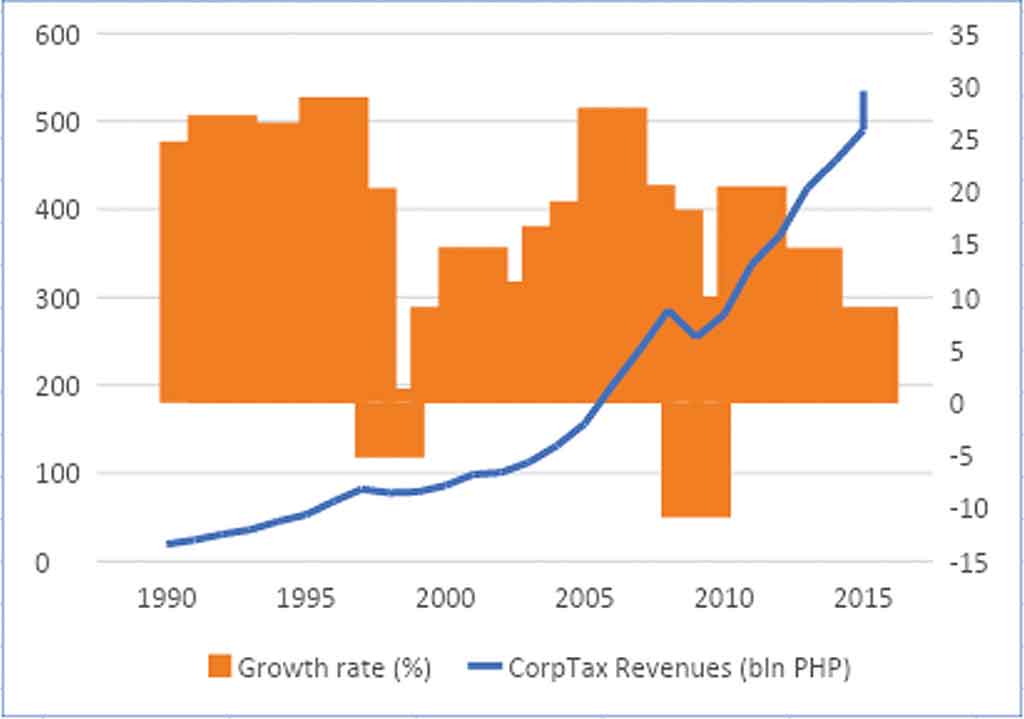

That CITIRA can help in the middle of the pandemic is doubtful. Figure 1 charts the increase in levels and growth rates of corporate tax revenues. The Figure is only up to 2016, but it suffices for this discussion. First, in both episodes of rate cuts, tax revenues fell. The rate cuts gave instantaneous relief to taxpayers, and that is all there is it to it in so far as revenues are concerned. To a government in need of higher tax income as it has to spend for social protection of the poor and to revive the economy, the corporate tax rate cut of CITIRA would appear not to be a help.

Revenues bounced back following the rate cuts, but they did so because the economy recovered. The regional and global economic crises in 1997 and 2008 were short in duration of one or two years, with sharp plunges and recovery.

Lower tax reduces the user cost of capital and increases investment demand. The tax reform in 1997 and 2009 might have contributed to the economic recovery. But will it deliver the same in 2020?

Unlikely. There are other factors which need to be considered. The effect on investments of a lower corporate tax will be outweighed by the uncertainty spawned by COVID-19. The health emergency has to end for good with the availability of vaccine and medicine which competent authorities have shown to be efficacious and safe. Absent that, we will still live as if we hide from our unseen enemy, the virus. That is not good for business. The last thing a new investor would want to be told is to close his new business to flatten some future wave of COVID-19 infections.

Access to effective and easy to use tests for COVID-19 can mitigate the uncertainty. But businessmen all over the world have to be persuaded that this pandemic is behind us.

Until the world has those medical antidotes, the prevailing risk to business can dampen, if not wipe out, the expected new investments that a lower corporate tax is expected to offer the economy. Without the expected rise in revenues due to lingering economic recession with COVID-19 still unchecked, reduced corporate tax will not help mitigate the fiscal deficit.

There is another factor to consider. Unlike its Asian or global counterpart, this global economic crisis is pandemic as well. There is not a single country ready to become the engine of the world economy. All major countries and regions — China, US, and the EU — are reeling from COVID-19 and the economic fallout that it induces. Although increasingly they are starting to open up their economies, all are trying to restart growth behind a backdrop that at any time authorities can order their constituents to go back into isolation to stop a possible future wave of infections.

EXPORTS AND INCENTIVES REFORM

CITIRA is designed to remove the privilege of the special 5% income tax privilege in lieu of national and local taxes in at least PEZA-administered economic zones. The exporters locating in these zones will be told to pay their national and local taxes the way all other taxpayers do. New projects of locators may still get a package of incentives, which proponents say are flexible and inclusive of non-tax measures to suit the requirements of companies which plan to invest in the country.

New projects of PEZA locators are eligible under the Strategic Investment Priority Plan (SIPP) with the Fiscal Incentives Review Board (FIRB) for incentives. Project owners would still have to show the FIRB that their projects bring in positive net benefits to the country. Some of these incentives include an income tax holiday (ITH) for two to six years; reduced corporate income tax rates after its ITH, or availment of special incentives such as tax deductions for expenses on training, research and development, and infrastructure facilities.

This planned reform of our investment incentives carries a great risk of us losing export competitiveness. The businesses in PEZA zones are all exporters, or most of them as some are indirect exporters. The businesses in PEZA zones make up our country’s capacity to export.

Exports from PEZA zones account for at least half of the country’s merchandise exports. In 2015, these businesses brought in about 59% of total merchandise exports, 65% in 2016, and 64% in 2017. Exports make up 29.2 % at 2018 prices of the country’s gross domestic product in 2019. This share has grown consistently since 2015, when it was only 25.3%.

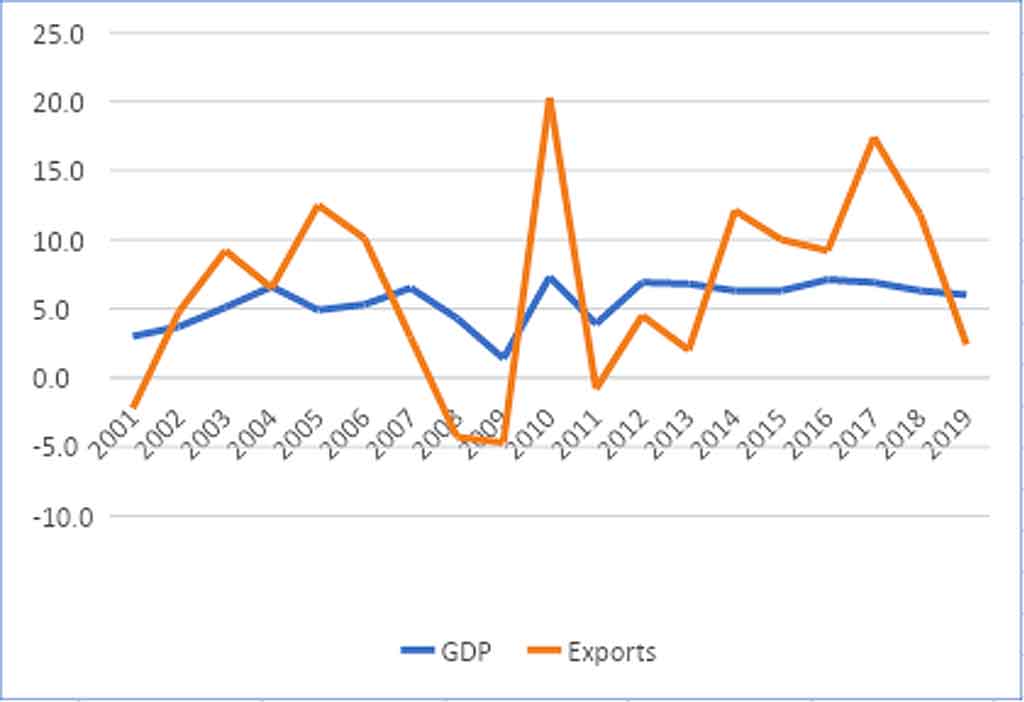

Export growth is an important determinant of overall economic growth, as shown in Figure 2. In the global economic crisis in 2008 and 2009, GDP growth plunged from 4.3% in 2008 to 1.4%. The export contraction in those two years appeared to pull economic growth down. In the first half of the Arroyo government in 2000 to 2005, annual export growth averaged 6.8%, and that pulled up GDP growth, except that we had political crises in those years which dampened economic growth. Absent that, high export growth pulled up GDP growth in the Aquino 2 and the current government. When export growth jumped from 2% in 2013 to 12.1% in 2014 and stayed in the two-digit rate range, economic growth was at least 6%.

Export growth slowed down in 2018 and 2019, and with COVID-19 and the ECQ in 2020, export growth is likely to be in the red once again. The trend is likely going to pull down GDP growth. It was still up in 2018 and 2019 because of the government’s infrastructure program. But the economy is likely to contract this year, as the first quarter GDP growth of -0.2% indicated.

PEZA businesses, the country’s export engine, are already adversely affected by the COVID-related ECQ. Some reports indicate that only half of the workforce were actually employed in the first half of 2020 because of ECQ and lack of imported materials. Profitability had declined as the ECQ-related spending required additional expense to export products or import materials. In 2019, a total of P22.9 billion were invested by PEZA locators, and if not for CITIRA and COVID-19, more investments would have been realized in 2020. In February this year, investments declined by 28% on a year-on- year basis.

CITIRA, if passed by the Senate in the middle of the crisis, may just compel locators to re-assess their location decisions. Some important businesses, like electronics which take up about half of the country’s merchandise exports, are portable. If the tax perks under this new reform are not those that would give the best return, they may just move somewhere else. Rather than help stimulate economic recovery, which is unlikely while COVID-19 is still around, the proposed law could cut down our export capacity in years to come, and dampens economic growth.

But there is still the opportunity to improve our proposed incentives reform law such that the country can sustain our export capacities and save jobs.

Ramon L. Clarete is a professor at the University of the Philippines School of Economics.