Which curve to flatten over the next few months?

The World Bank in its economic update of the East Asia and the Pacific dated April 2020 has COVID-19 as its theme. The update bears disappointing facts regarding significant slowing down of several growth drivers. While under a normal situation, global and national economic managers can take corrective actions to boost performance, the problem is we live in extraordinary times because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the unavoidable economic cost of containing COVID-19 and saving lives, the world may likely expect another type of a pandemic — a global economic recession.

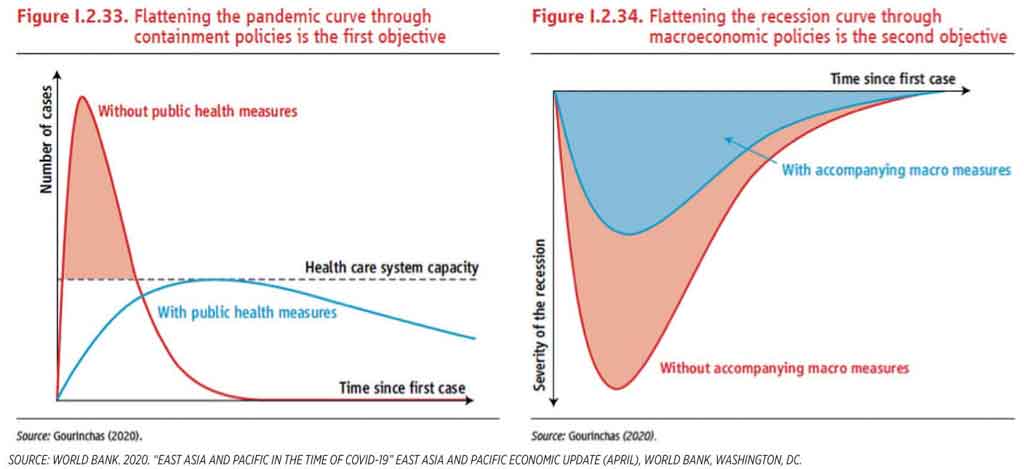

The update talks about the infection and recession curves of COVID-19. Both are interrelated, flattening one steepens the other. The first is what we hear from health experts and national leaders. The UP COVID-19 Pandemic Response Team did mathematical simulations of the curve, and noted that the “epidemic in Metro Manila will happen between April and June 2020”as reported out in the Philippine Star (see https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2020/04/03/2005234/covid-19-strategy-heres-how-philippines-can-combat-pandemic-according-data-scientist).

There are several measures to reduce the number of COVID-19 cases, but the most effective would seem to be what China had done in Wuhan: a city lockdown. Other measures are needed to make the lockdown even more effective, such as social distancing and temporary suspension of the school system at the community level, as well as lifestyle changes at the personal level to reduce the risk of getting ourselves infected. We have a similar response here to contain COVID-19, the enhanced community quarantine or ECQ for the island of Luzon.

Lockdowns are by far the most aggressively effective and most countries are just forced to take it to flatten the infection curve, except Sweden. And that is because healthcare system capacity is fixed in the short run, although the Chinese government demonstrated that they can expand capacity in less than a month. Most countries have healthcare systems built for a normal situation, and a COVID-19 pandemic is extraordinary.

But lockdowns are economically costly, and this is what the recession curve is all about. People out of job in an ECQ disrupts the circular flow of income and spending as earning members of millions of families have to stay out of work, and this slows down, if not reverses, economic growth. Other industries are affected adversely as the circular flow of income and spending is disrupted. What is demonstrably effective in flattening the infection curve has the undesirable effect of deliberately inducing a recession of the economy.

But admittedly doing nothing would steepen both curves. As more and more people get infected and the healthcare capacity is inadequate to cure them, productivity of the economy declines, boosting the recession curve.

If I may just use the two Figures from the update, the two curves may look like this. (See the figures.)

The duration of the lockdown period is uncertain. We just know when it is no longer needed, when the curve is flattened to a level suited for the country’s prevailing healthcare capacity. But not quite. The COVID-19 infection curve simulators of UPLB noted that even a flattened infection curve can rise again with new cases. Our ECQ was targeted to be lifted on April 15, after this Holy Week, two days from now. But last week we were informed Luzon needs two more weeks. But who really knows if that added duration is enough?

It is a quandary on the part of the government. Our leaders and health experts do not know with certainty how much time they need to flatten the infection curve for good. But the longer they force people to stay home, they end up sharpening the recession curve.

In practice, governments have to flatten both infection and recession curves. There has to be some capacity constraint that eventually compels authorities to flatten the recession curve, even as it reduces the number of new cases. The constraint may be the political capital of a country’s leaders. As people lose their incomes for an extended period of time, the political support for the government declines. Before its political capital gets completely depleted, the government would have to do something to relieve the pain induced by lockdowns, i.e. flatten the recession curve.

Congress enacted its anti-COVID emergency law, RA 11469, to help the poor cope with income losses due to the ECQ. According to the Finance Department, P200 billion is needed to sustain emergency assistance to millions of our countrymen, who are on “no-work, no-pay” arrangements over a period of two months.

Beyond May 2020, the government would have to borrow money to sustain the subsidy if the ECQ would still have to be continued by then, and quickly resuscitate the economy back to stronger growth. The World Bank has already provided the government a $100 million loan facility to help fight off COVID-19. Moreover, the government is negotiating with the World Bank and ADB for several hundreds of millions of dollars more in loans to flatten both curves.

The economy is expected to shrink by 0.6 of a percent, says National Economic and Development Authority Director General and Socio-Economic Planning Secretary Ernesto Pernia, if no intervention is done by the government, including the emergency income assistance infusion of P100 billion pesos a month.

Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III said that if the lockdown would last for only three months the economy could still lock in a 4.3 % GDP growth for 2020. But that is still recessionary compared to the stronger growth we had until COVID-19 hit us. With the base of the tax reform program reduced, the resources that the government can use to boost the economy are expectedly limited. The “Build, Build, Build” infrastructure program, which has been successful in sustaining high growth at 6% or above can be slowed down.

By the end of April, when the country is still before the peak of the curve, our leaders may consider extending the ECQ in Luzon. Because if they lift that prematurely to get the economy back up and running, the gain from staying at home in terms of fewer new COVID-19 cases in the last month and a half could be neutralized with a new wave of infections, a concern of China now as it lifts the lockdown at Wuhan city. Scientists are even saying now that we may have to continue lockdowns and social distancing, until we have the vaccine for COVID-19. But that is several months away.

But if that second wave in China turns out very weak, and if President Donald Trump has his way and would have restarted the US economy, these developments could persuade our leaders here to end the lockdown, or modify the social distancing rules. That would be great news if indeed the situation would have called for such a move.

Testing, testing, and testing for COVID-19 is really important. With more information about the enemy, we can adjust our policy responses with a lower cost to the economy. So what is it that we need to do to get us all tested at the same rate as we buy Chickenjoy from Jollibee?

Recent data from the Department of Health (DoH) appear to indicate that the infection curve is getting flatter. Obviously, the DoH data is selectively biased. It covers those cases that are only revealed to health authorities because they tested them. The sample is very small relatively to the entire population. The data does not capture infections outside of the system, and we do not know how bad that is for now.

Given these caveats (and this is the only data I have), the following Table shows the daily new cases since the last week of March to April 9. I took a three-day moving average to tone down the irregularities of testing and reporting. The daily new cases are plotted in the Chart.

I broke down the number of observations into weeks and took linear trends of each set of data. In the last week of March, there were 234 cases per day. The number worsened in the first week of April to 285 cases. But in the second week of April, it dropped to 191.8 cases, which, if sustained in the following week, indicates that the ECQ may be working. But that may still change for the worse. Hopefully, the recent trend is going to be sustained.

I am not concluding at all that the curve is flattened or just about to be flattened. It is an observation given the limited data that I have. I agree with our UPLB scientists that this observation of the infection curve may go up again, or may stay flat for good. By April 30, the government would need as much evidence as it can mobilize to guide its policy on lifting or continuing the ECQ, whatever is necessary to flatten both the infection and recession curves.

Ramon L. Clarete is a professor at the University of the Philippines School of Economics.