The paths, familiar.

The job, a source of income.

The duty, a mandate.

So, how did he end up here?

A day in the life of a Corillera mailman

Jordan H. Bungtiwen, 41, had been a kartero for the Philippine Post Office (PHLPost) for roughly five months when a team from BusinessWorld tagged along with him on Nov. 23, 2022.

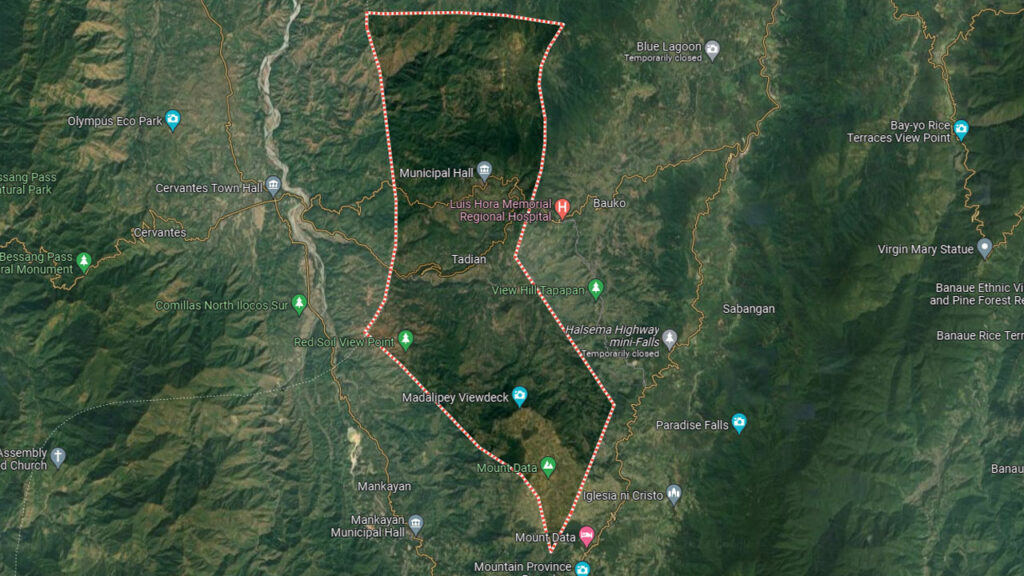

Mr. Bungtiwen services Tadian, a small town of 19 villages, in the mountainous Cordillera Administrative Region in North Luzon. Remote and landlocked, it has about 21,000 residents who rely on Mr. Bungtiwen. He splits letter carrier duties with the town’s postmaster, Gertrude L. Lampacan.

Mr. Bungtiwen’s route offers breathtaking views but is not a walk in the park as some would think. As routine as his journeys may be, this time to deliver national IDs, the long walks, rough roads, the up and down paths have always posed a physical challenge.

Despite this, Mr. Bungtiwen, who used to work as a village watchman in Tadian and only made P13,000 every three months, said he is grateful for his new job as a mailman.

THE PHILIPPINE POST OFFICE

THE PHILIPPINE POST OFFICE

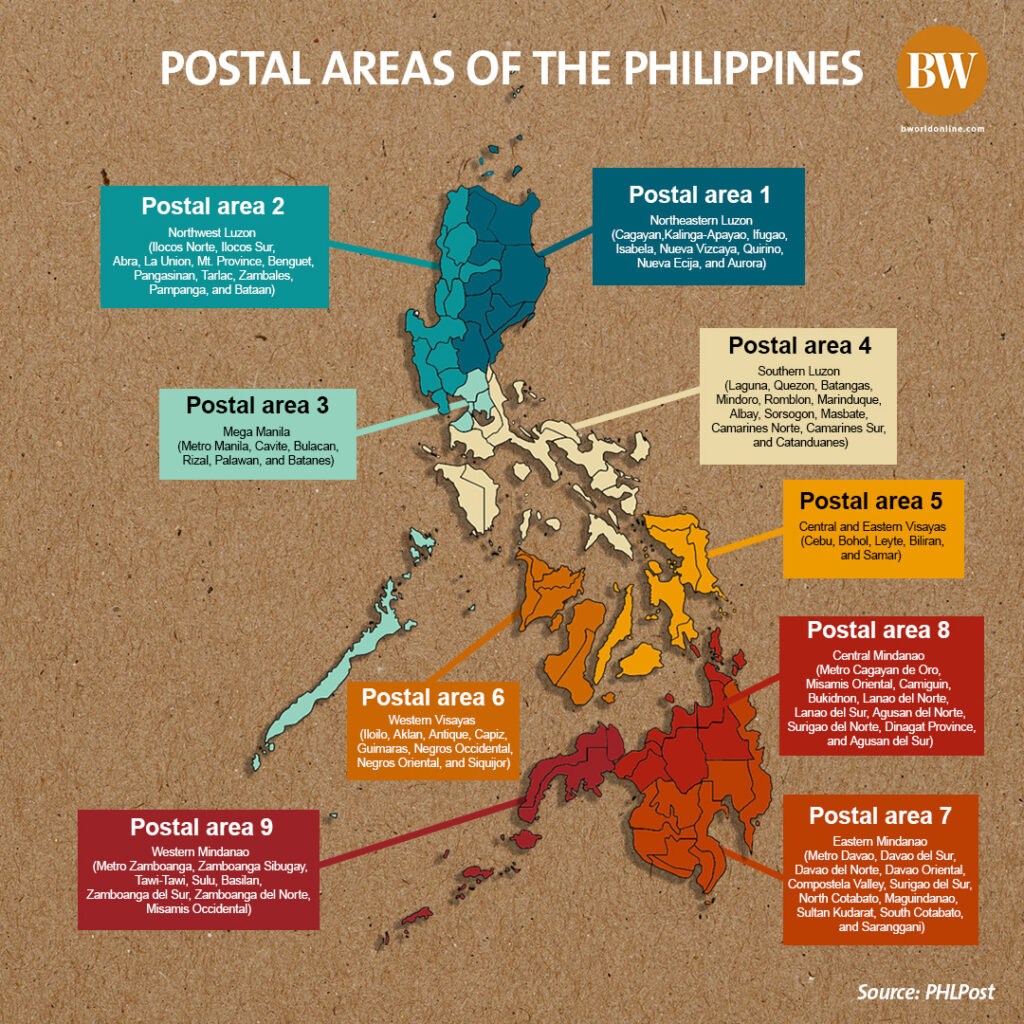

Mr. Bungtiwen is one of the 4,200 mailmen employed by the government-run PHLPost, which has been in operation for over two centuries.

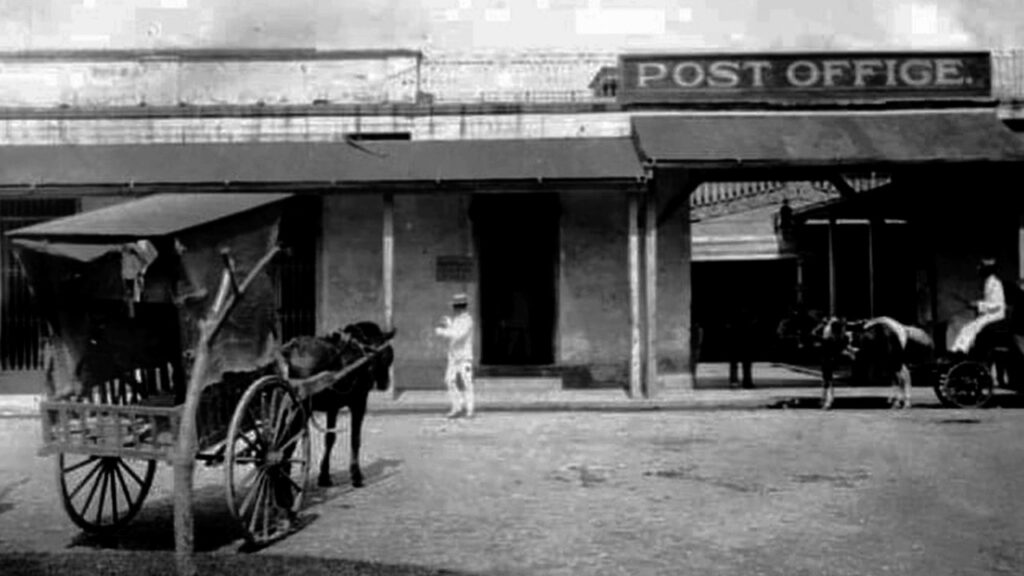

The office was formalized as a postal service provider between 1783 to 1784 and has since been the go-to courier for all 81 provinces in the country.

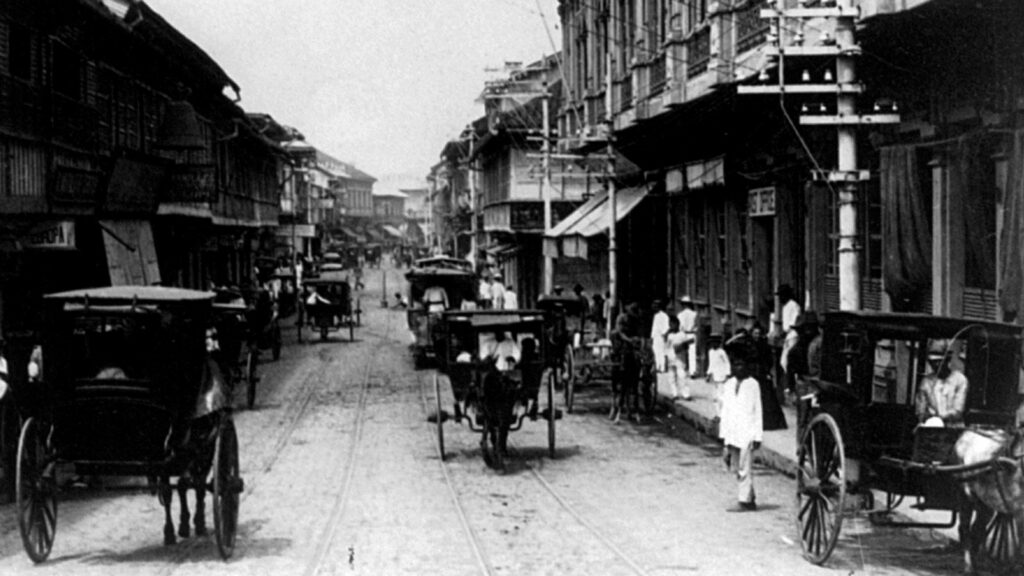

Manila became the country’s hub for letters sent and received to and from Spain upon the establishment of its first post office in 1767.

Rates and routes were established in 1783-1784, formalizing the country’s postal service. Spanish ships carried Philippine mail to Europe via Mexico in 1783. Postal offices likewise sprouted in Cavite, Batangas, Bulacan, Tondo, Pampanga, Bataan, and Laguna.

In 1875, Spain became part of the Universal Postal Union, the primary forum for cooperation among postal sector players. But it was not until 1922 that the Philippines joined the forum as a sovereign entity.

Norman N. Fulgencio, the postmaster general, said his office’s mandate is its key differentiator.

“Sa mga fifth, sixth class municipalities, wala naman diyang (In fifth and sixth class municipalities, you are not going to find) private corporations,” he said in an interview.

It is our mandate to serve each individual, Mr. Fulgencio noted. “Whether it’s in the mountain or the smallest island…pupunta kami diyan once a week, once a month, depende kung gaano ka kalayo (We will be there once a week, once a month, depending on how far you are).”

“We will travel by boat for two, three days to reach you,” he added. https://youtu.be/ZRqquQV4adA

POSTMASTER GENERAL ASSURES

“Sa mga fifth, sixth class municipalities, wala naman diyang (In fifth and sixth class municipalities, you are not going to find) private corporations,” he said in an interview.

It is our mandate to serve each individual, Mr. Fulgencio noted. “Whether it’s in the mountain or the smallest island…pupunta kami diyan once a week, once a month, depende kung gaano ka kalayo (We will be there once a week, once a month, depending on how far you are).”

“We will travel by boat for two, three days to reach you,” he added.

THE PROCESS

THE PROCESS

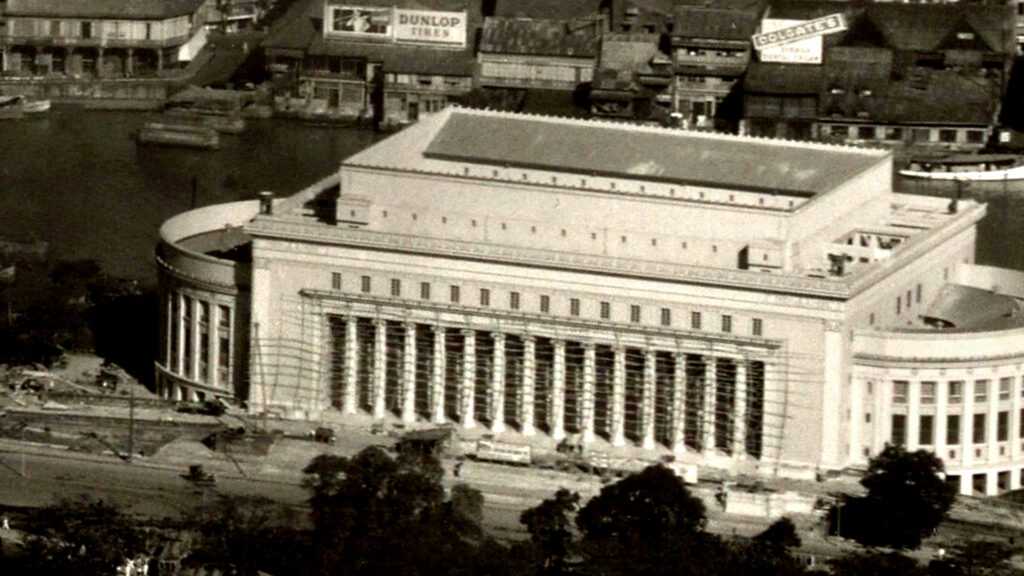

The post office’s sorting center in Pasay City handles all incoming and outgoing air mail for the country. There is a separate sorting center in the city of Manila specifically for sea mail.

According to Rosario A. Adriano, the acting manager of PHLPost’s Business Lines Department, there are two daily dispatches for outbound international mail.

“Domestic parcels leave at 4 a.m. to be distributed across regional post offices,” she said in an interview. “International parcels are dispatched to the airport at 8 to 10 a.m., and also at 4 to 8 p.m.”

Incoming mail typically begins arriving daily from 10 p.m. to 1 a.m.

All items at the arrival dock undergo x-ray scanning by Customs officers. Those requiring additional inspection are marked with an “X” and taken to the inspection area within the sorting facility.

Parcels are checked to ensure that no prohibited items pass through, said Roger M. Tumlos, acting manager of the express mail exchange department. Parcels that have a value of more than P10,000. are subject to customs taxes.

“There are also items that are regulated, meaning they are allowed, provided they have permits from the concerned government agencies,” he said, referring to plants, firearms, and compact discs (CDs).

“Actually, konti na lang ang contraband items (only a few contraband items manage to pass through),” Mr. Tumlos added.

“Paminsan-minsan, illegal drugs ang pumapasok, pero marami pa rin yung mga medications, lalo na yung mga gamot sa cancer. Mahal kasi dito. (Illegal drugs would sometimes come in, but a lot of times we see cancer medications being sent, because they’re expensive here).”

Mr. Tumlos said such medications, bought from countries like India and Pakistan, are released, although these are still subject to the maximum allowable quantity.

PHLPost’s express mail service or EMS delivers time-sensitive items locally or internationally. More than 40 countries have EMS exchange deals with the Philippines.

Letter posts, on the other hand, are items under two kilos, including priority mail and registered mail, which is accorded mail security, with the entire process being recorded from acceptance to delivery to the addressee.

When a recipient’s address is incorrect or incomplete, the package is often returned to the sender.

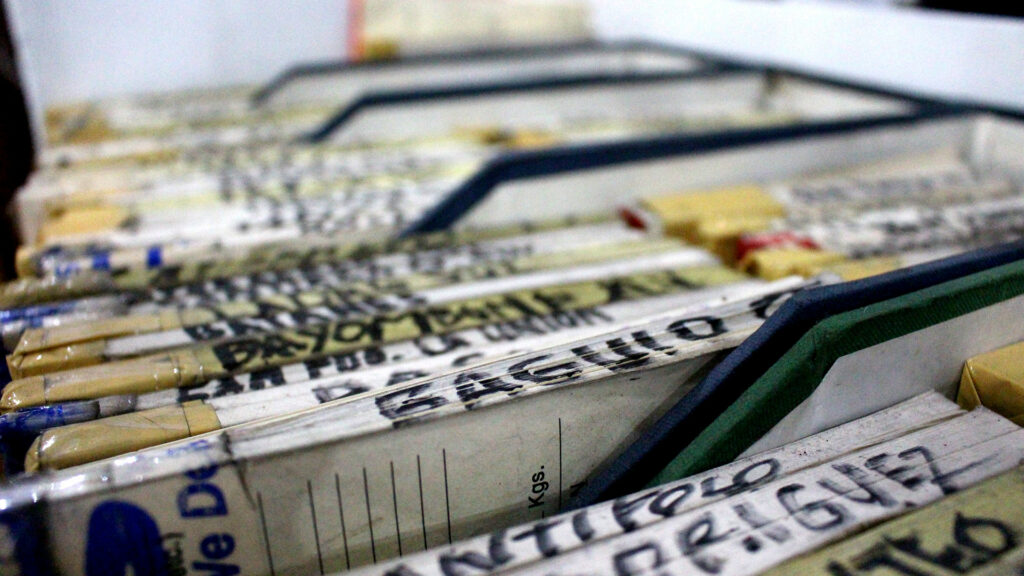

As the PHLPost’s systems are only partially digitalized at present, surface mail staff in their Manila sorting center still wrote down the details of undelivered letters and parcels in a physical logbook.

In 2021, during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, PHLPost delivered 109.3 million letters and parcels, a 40% increase from the previous year, mainly due to the e-commerce boom amid strict quarantine rules. The number of undelivered items also rose sharply, from 2.4 million to 4.3 million, an 81% increase from 2020.

Just after daybreak, Mr. Bungtiwen wakes up to a cool breeze after a restful night’s sleep.

His family’s home, which was constructed under a government aid program, stands on a mountain.

According to the mailman, eating a hearty breakfast of corn porridge provides him with enough strength to fulfill his daily tasks.

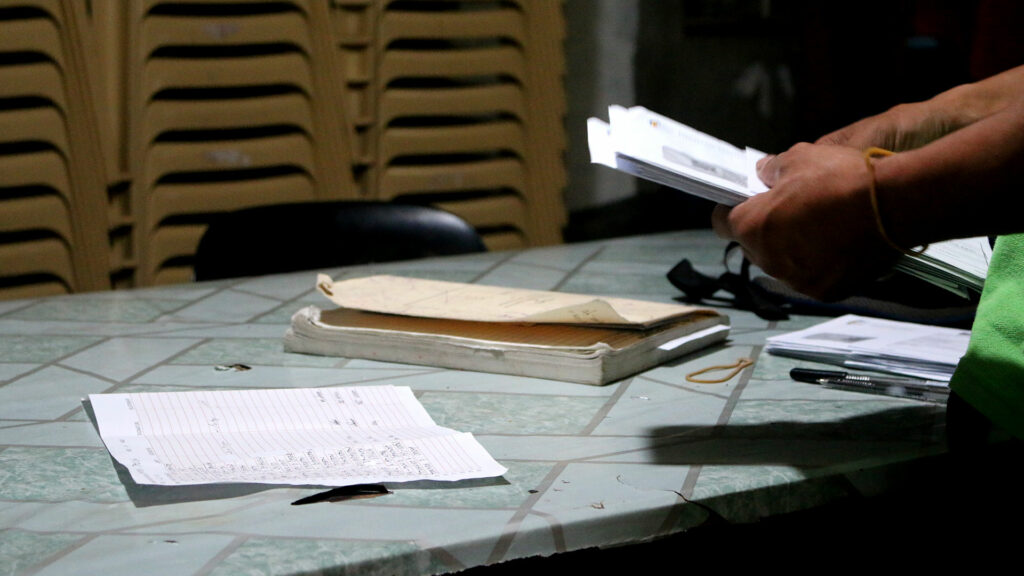

After preparing his usual workday essentials, his logbook and a packed meal for lunch, Mr. Bungtiwen dons the green PHLPost uniform in place of his red pambahay (comfort) shirt.

He sets off from his home for another day of deliveries to the residents of Tadian.

It is 8 a.m., and Mr. Bungtiwen arrives just in time to start his day as a mailman.

With walls still covered with soundproofing boards from its time housing a radio station, the Tadian post office is Mr. Bungtiwen’s place of work.

He takes his time sifting through parcels, carefully plotting the delivery route in his mind. His deliveries that day were all national IDs.

The 19 villages in the Tadian town are separated from each other by mountains, rice paddies, and concrete roads.

Maria Abigail D. Tarroza, researcher and news editor of PHLPost’s corporate communications division under the office of the Postmaster General, said that the letter carriers are trusted members of their respective communities.

They have to be, she said, especially in areas where conflicts are rife.

Mr. Bungtiwen, who is from Ifugao, moved to Tadian when he met his wife, a Duagan native.

That sunny day, the mailman was scheduled to visit three villages: Lubon, Duagan, and Sumadel.

The path to Lubon, the first destination in the day’s schedule, snakes here and there, making one wonder where the path ends, until – quite suddenly – an opening appears, revealing a rice field, a large pile of rocks, and a cemented staircase leading to the community.

Everyone seems to know the Tadian town’s letter carrier.

He happened to pass by a daycare center, where the children shyly played hide-and-seek with visitors, even as they gamely smiled for the camera. Mr. Bungtiwen’s wife, Josephine, happens to work for a barangay daycare center herself.

Lubon’s residents were enjoying a quiet morning tending to their children when Mr. Bungtiwen dropped by to fulfill his tasks. Today, all the mail recipients were home, which made ticking off the to-do list easy.

After all the mail has been dispatched, Mr. Bungtiwen proceeds along his journey, where he bumps into a local herding his carabao home. He also passes by an abandoned car or two that have now become part of the scenery.

Shortly past 1:00 p.m., and it’s off to the second village, Duagan.

The place is even more remote than the first. With about 200 to 300 residents calling it their home.

It is so remote that visitors are rare, and thus easily spotted.

Reaching Duagan means traversing a road that is only cemented part of the way through, and then crossing another set of rice paddies.

There is no dearth of warmth in Duagan. Visitors lucky enough to drop by during a break in the village hall’s activities will be offered refreshments and a place to rest.

Visitors in the area will notice a sign outside the hall that reads, “No Spitting Momma,” which is not a reference to one’s mother. “Momma” is a local chewing gum made from betel nut and may include tobacco and peppermint. Its reddish hue often stains a person’s teeth.

The group reached the third and final destination, Sumadel, as dusk approached, and the mountain chill had set in.

Sumadel has more concrete structures than the previous two villages, including a roofed basketball court and a gym atop a nearby mountain.

The vibe in the community is close-knit.

From the school children milling about the community hall, to the family along the riverbank, to the shopkeeper in the sari-sari store (mom-and-pop shop), Mr. Bungtiwen goes about his task with a practiced air.

He delivers his final mail just as dusk sets over the countryside.

t is not unusual for the mailman to deliver mail past the typical work hours of 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., according to the post office.

“One time our mayor saw Jordan past 6:00 p.m. in one barangay and asked, ‘What are you still doing here?’” Ms. Lampacan said in Filipino. “That’s because past five is when the residents come home each day from work.”

The residents of all three villages are friendly folk who seem surprised to see outsiders.

“What brings you here?” was the common and bemused question residents asked of outsiders as they exchanged pleasantries with the mailman in a mixture of the local languages Kankanaey, Aplay, and Ilocano.

Ms. Lampacan, who accompanied the team and Mr. Bungtiwen, shared that some were not keen on receiving their national IDs anymore.

“It’s not accepted as a valid ID in the Tadian branch of the Department of Social and Welfare Development, as well as in Landbank Bontoc, because it doesn’t show the person’s signature,” she said in Filipino.

Landbank told one resident to get a voter’s ID instead, the postmaster general added.

Mr. Bungtiwen’s job is not easy, especially during the rainy season, but his perseverance stems from his desire to provide a better life for his family.

He has big dreams for his four children, including his eldest son, who is pursuing a college degree and aspiring to become a police officer.

With his current daily wage of P500, he and his wife, who works at a daycare center, can better provide for their family’s needs, the mailman said.

He treasures his children’s aspirations, knowing that they hold the key to the family’s success.

“Pangarap kong makatapos sila ng kanilang pag-aaral (My dream for my children is for them to finish their studies),” he said.

No matter how high the mountains are, how remote the places could be, all the challenges he faces daily seemed inconsequential compared to the dream of a better future for his family.