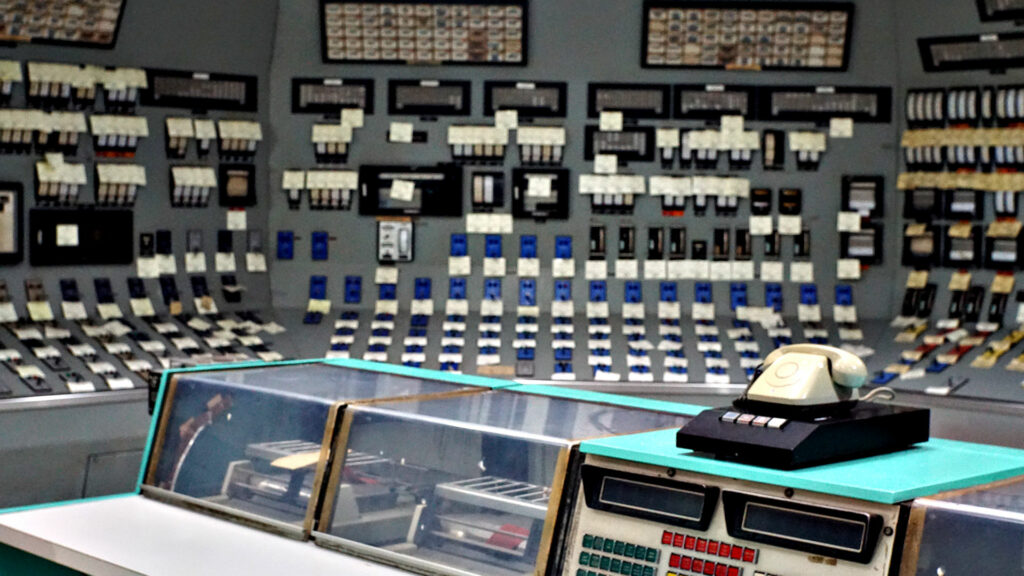

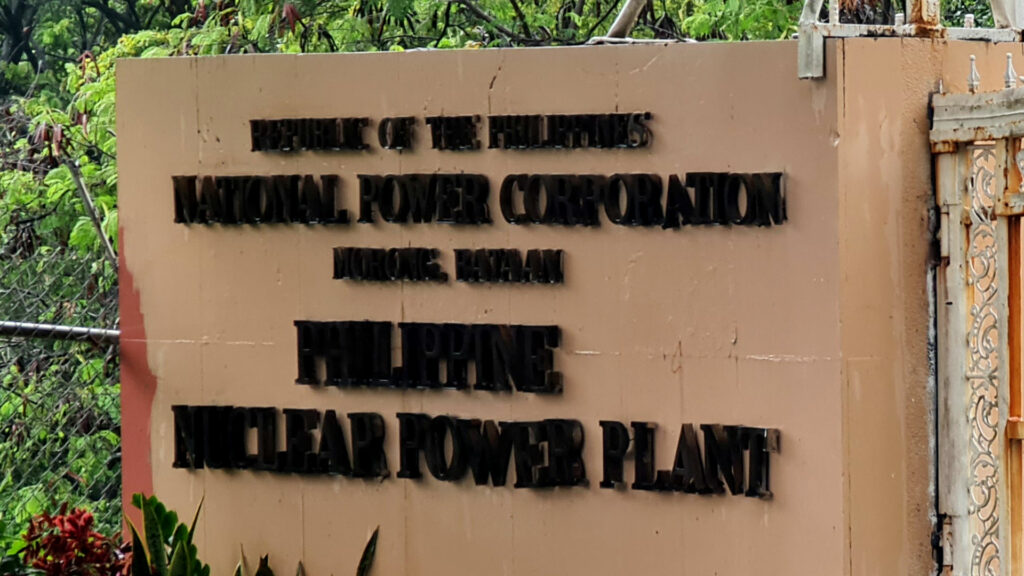

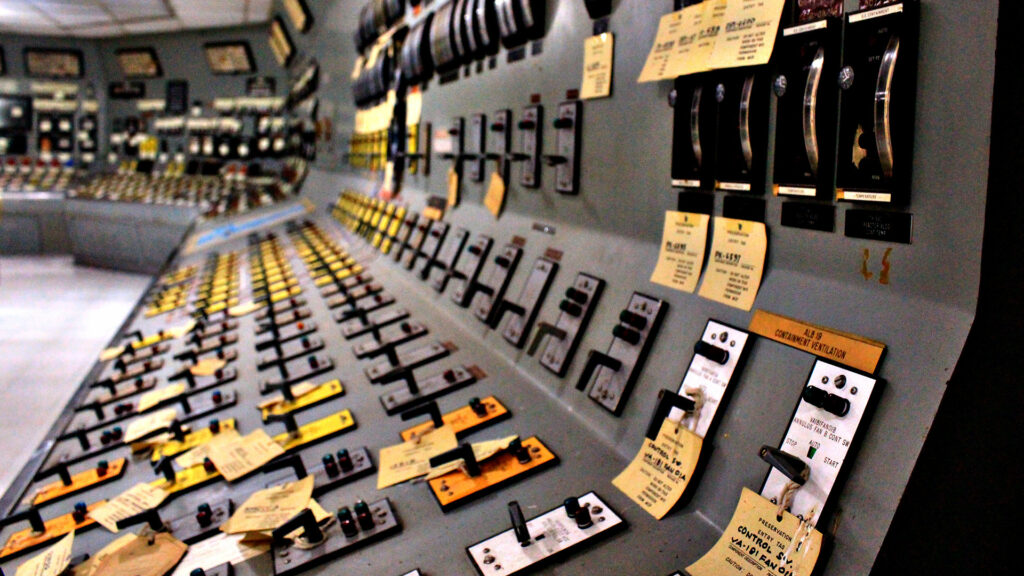

Sleeping atop Napot Point, 18 meters above sea level, the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP) stands as a concrete reminder for unrealized plans of energy sustainability.

The Philippines, now facing surging oil prices and a strained power grid, has had two consecutive presidents putting their stake on nuclear energy, but the matter has remained controversial. Nuclear power in the country, with a history impossible to disentangle from Philippine politics, is an often misunderstood science.

With the promise and potential of the now-defunct BNPP back in the national discourse, the onus is now on us to determine: what should Filipinos know, look forward to, and watch out for?