A market-friendly way of reducing medicine prices

About two weeks ago, President Rodrigo R. Duterte, in an interview with Ted Failon from ABS-CBN, said that he will sign an executive order imposing a limit on the prices of certain medicines. “That’s good for the Filipino, reduced prices or maintaining a price. I will even sign the document twice over,” the President said.

President Duterte referred to a draft of a Department of Health Administrative Order (DoH-AO) entitled “Guidelines for the Implementation of Maximum Retail Price (MRP) on Drugs and Medicines.” Reportedly, the document is not on the desk of the President yet, and is presently reviewed by the relevant rest of his government.

As users, we are all for lower costs of medicine. I cannot say that that is true for the manufacturers, multinationals, or the local pharmaceutical generic companies. But I say that each of them should be for lower prices of medicines, not because their hearts bleed for the families who sink into poverty if a family member is stricken with a disease that can only be treated with very expensive medicines. But because lower prices increase their market share, and in a highly competitive medicines industry, reduced prices can be a good marketing strategy.

The industry is made up of monopolists. The right to sell a medicine in the market is protected with a trademark, which accords the owner the right to exclusively market its product. But — and this is an important difference with an industry with a single supplier — there are other medicines which are as functionally effective in curing a disease. The companies are monopolistically competitive. All the medicines in the market that are functionally equivalent in treating a disease are differentiated from each other to cater to a particular need or preference of a subset of buyers, and this make each company in the industry monopolists with respect to their own product, but they have to compete with other monopolists.

True, in the first 21 years of the commercial life of a useful pharmaceutical ingredient, the company which first developed the ingredient has exclusive right under our patent law to market the product containing it. The privilege is important to encourage research and development of new and useful medicines. But once the ingredient is off patent, then other companies can use it and introduce slight differentiation on the ingredient to cater to the need or preference of a particular segment of the market, and produce a new product that can be protected with a trademark.

But because there are several medicines which contain the same pharmaceutical ingredient in the market, the firms are always competing with each other. Since they are monopolists, each of them decides at what price it sells its medicine. If the price is just too high, buyers can shift to competing medicines and the company’s share in the market declines. It can reduce its price and gain more revenues. It is not a zero-sum game since the lower price induces more revenues but still market shares would differ.

AN OPPORTUNITY UNDER THE UNIVERSAL HEALTH CARE LAW

The government has the opportunity under the universal health care law to be innovative in solving the problem of high out-of-pocket costs on medicines — an approach that is more market friendly. It can induce more competition among the drug makers through the centralized procurement of medicines. Dividing the medicine procurement among scores of procuring authorities removes the government’s leverage to negotiate the lowest price of a medicine in exchange for a larger volume.

A monopolistically competitive firm can agree to lower its price up to its average cost of producing the product. Average costs goes down with volume because the firm has sunk fixed cost in differentiating its product from other functionally equivalent medicines of other companies. Its capacity to bring down its price depends upon the cost it spent in coming up with its medicine.

Decentralized procurement of medicines by the public sector eliminates the opportunity for the government to make a good deal with the pharmaceutical company. A smaller volume by one procuring authority is not attractive for companies to participate in bidding. This and unrealistically low ceiling unit bids prescribed by the health department would only attract a few bidders in the market, typically the smaller ones which have relatively sunk lower fixed cost in developing their respective products.

Medicine prices then continue to be priced high. Lower volumes sold would mean higher average unit costs of companies, and higher prices. Larger volumes sold through central procurement can bring down average costs as fixed costs are spread out, reducing medicine prices.

The solution is not that easy to do, particularly in an environment of imperfectly coordinated public bureaucracy in the health sector, not to mention the lingering problem of corruption. The central procuring authority has to plan out well the government’s requirements. Gathering information on this is a challenge. We don’t want a situation where some central procuring authority is procuring medicines that some of the public users do not want. An organization of the Department of Health family in coordination with the local government units is needed. The health department may want to know from experts how this can be done.

Then there is the problem of distributing the procured medicines. The good result is that the procured medicine is needed, delivered at the right time, and to the right place. The effective distribution of procured medicines is another challenge for the central procuring authority in addition to planning for an effective central procurement of medicines. Once again, the health department may want to know how the private commercial sector does this task.

The Universal Health Care Law gives the Department of Health this opportunity of a market-friendly approach of bringing down medicine prices, but it has serious challenges to overcome: planning the procurement, executing the bids efficiently, and timely and accurate distribution of medicines to the rest of the health sector bureaucracy.

TREND IS PRICE NEGOTIATIONS

As a solution to high out-of-pocket costs on medicines, maximum drug retail prices (MDRP) belongs to the past. It is, in the first place, premised on shaky ground: the assumption that we charge higher prices here compared to other countries. In design following the guidelines of the health department to implement it, one of the criteria used for including medicines in the program is if their local prices exceed the external reference prices of medicines compiled by the World Health Organization (WHO). However, WHO failed to adjust prices of medicines of several countries for differences in time, exchange rate, health care policies, and other factors between countries (Cameron et al. 2011). This cast doubt on the validity of the price premia of medicines in the Philippines over international prices.

Long term consequences of price controls have always been known to be bad for consumers and producers. As users of medicines, we may be happy to see the prices of medicines go down. But after some years, important medicines may disappear from the local market, and we would be forced to import those from abroad. There can issues on timing and cost of access, and, more importantly, the efficacy of medicines. In the long run, users may be worse off with medicine price capping.

Policymakers often cited India as a model where drug prices are lower than in the Philippines. But according to one account published in BusinessWorld (https://www.bworldonline.com/price-controls-on-drugs-are-not-a-good-idea/), Professor Amir Ullah Khan of the MCR HRDI Institute, Government of Telangana, India enumerated several problems that India experienced with price capping. These included (a.) reduced consumption of medicines; (b.) reduced medicines access of rural areas; (c.) decline of new drug launches; and, (d.) out-of-pocket costs for healthcare did not go down as health care institutions recouped their losses from price capping by charging higher for use of facilities.

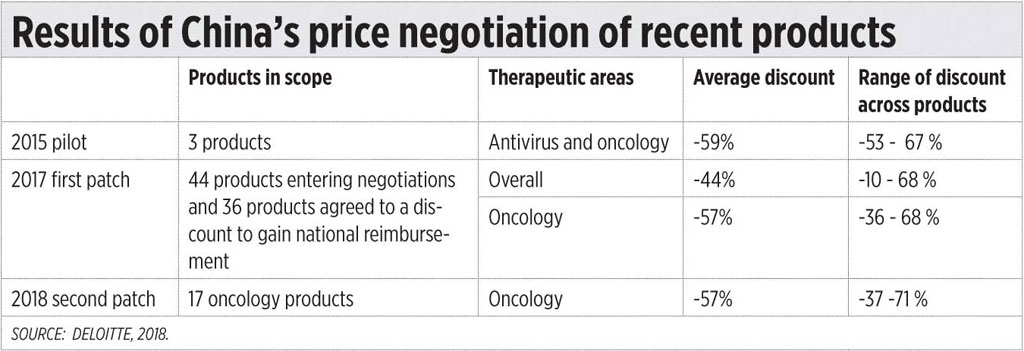

Recent trends in other countries are towards price negotiations. Two studies (one which appeared in Deloitte Insights in 2018 entitled, “A new view on market access and reimbursement: Launching innovative biopharma in China”; and another, which appeared in 2018 in the Value in Health Regional Issues, an Elsevier Journal, on “Recent Pricing Negotiations on Innovative Medicines Pilot in China: Experiences, Implications, and Suggestions,” by several authors) documented the gains China had by using price negotiations on innovative medicines.

In China, for users to benefit from medical insurance, the medicines have to be in its national drug formulary, of which there are two lists. The A list contains the essential medicines which must be available in all health care facilities sin China. The B list may include new drugs following an extensive evaluation and price negotiations, including expensive innovative medicines for diseases like cancer which are normally excluded. The manufacturers can apply for inclusionin List B subject to several criteria including a mutually negotiated price of the product.

Deloitte documented some of these gains. Medicine prices did go down significantly but not because of price capping, but because of price negotiations. (See the table.)

Perhaps, we can learn more from China and India on price capping and price negotiations.

Ramon L. Clarete is a professor at the University of the Philippines School of Economics.