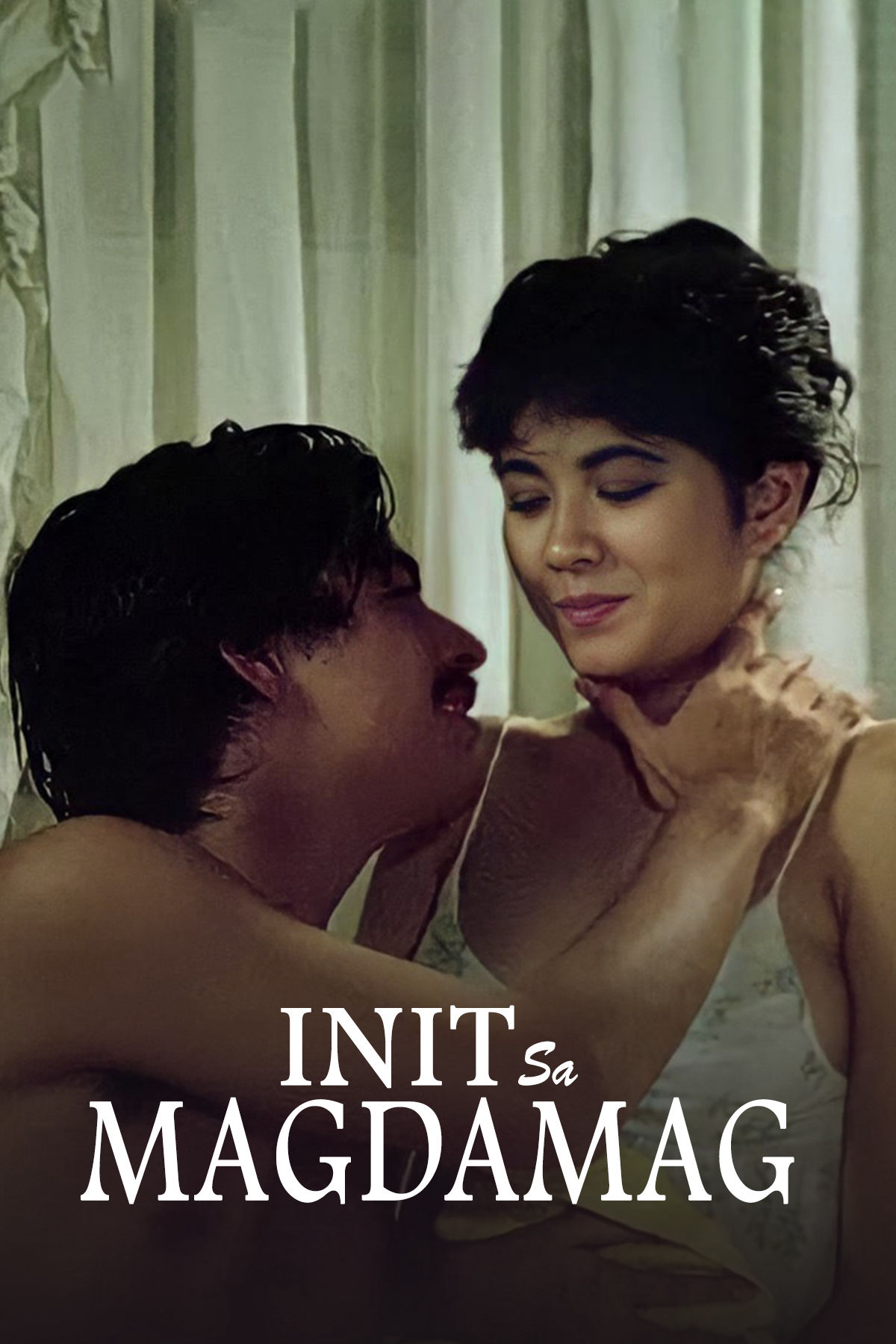

Init sa Magdamag, 40 years later

Critic After Dark Noel Vera

Movie Review

Init sa Magdamag

Directed by Laurice Guillen

A restored version of this film

is available on Vivamax.net

(Warning: details of the plot discussed in explicit detail)

THE FILM starts wordlessly in a hotel suite, with Mr. Eleazar (Ding Salvador) humming “Bessame Mucho” as he disrobes and Irene Trejon (Lorna Tolentino) sitting in her bubble bath. She hears a gasp and solid tonk! pulls the shower curtain aside, sees Mr. Eleazar on the floor, sees the slow-pooling blood.

THE FILM starts wordlessly in a hotel suite, with Mr. Eleazar (Ding Salvador) humming “Bessame Mucho” as he disrobes and Irene Trejon (Lorna Tolentino) sitting in her bubble bath. She hears a gasp and solid tonk! pulls the shower curtain aside, sees Mr. Eleazar on the floor, sees the slow-pooling blood.

Shock and dismay. Cut to a fully dressed Irene glancing back before leaving through a pair of sliding doors. The camera pauses to wander over the TV set, the furnishings, the bed with its immaculate dustcover (Why immaculate? Because they hadn’t had the chance at sex), before returning to the gaping door, a lingering languorous shot that both opens and sums up the film: empty room, sordid scenario, camera following the departed woman into the dark — into the depths, so to speak, of the woman’s psyche.

The woman again, this time putting on her face before a mirror, kissing her sleeping boyfriend goodbye. We follow as she takes up a position behind a bank counter and learn her name: fresh hire Becky Claudio, summoned by Mr. Perez (Leo Martinez) to his office to fill in gaps in her employment record. Like Laurice Guillen’s camera, Mr. Perez uncovers little: she worked with Felix Wear — now bankrupt — and her boss can’t give references because he’s emigrated to Canada. The interview is comically awkward; Mr. Perez is intrigued and wants sex, but hasn’t the guts to ask.

Next is boyfriend’s turn: in a series of languorous long takes atop a bed we watch Armand (Joel Torre) grill Becky on her past. “How many boyfriends have you had?” “Six.” “I’m seventh?” “Seven is a lucky number.”

Armand doesn’t like her answer. Becky relents to only two — can’t remember anything about her first. “We broke up. That’s how stories end, right? I forgot him, he forgot me.”

Irene later Becky later Leah Sanchez is Guillen and writer Raquel Villavicencio’s woman protagonist; as incarnated by the cabal’s third member Lorna Tolentino, she’s a catlike chameleon of a creature difficult to pinpoint in space and time, affix to a definite image. Darkly handsome Jaime (Dindo Fernando) learns this to his dismay: he notices Leah, turns briefly away, and she’s gone. “You play the game well,” Jaime tells her when he finally catches up. “What game?” Leah asks. “Cat and mouse.” “Are you married?” “Aren’t we all? But my wife’s abroad.” “So that’s it; when the cat’s away the mice will play.” “But I’m the mouse,” Jaime insists. “You’re the cat, you’re too inquisitive,” says Leah, adding “but you know everything.”

“Except about you,” says Jaime. “What do you want to know?” Leah asks. “Everything,” Jaime replies. “Nothing.” Leah is as quickwitted a conversationalist as Jaime and his superior at hide and seek — she has to be, to evade predators. Guillen’s camera follows as Leah slips in and out of the frame, “follow” being the operative word: like Jaime, Guillen’s camera has trouble keeping up.

Stories and games; stories with Armand, games with Jaime. Becky tells Armand the story of seven boyfriends; he’s displeased, so she knocks the number down to two (including him); Leah and Jaime flirt in the playful tone of carnivores sizing each other up for the kill; later Jaime reminds Leah of this — that she’s a good player, perhaps the best he’s ever known.

As Irene becomes Becky becomes Leah, Guillen marks each transition with water imagery, with Irene pushing aside a glass door (vertical sheet of frozen water) to depart; with Becky peering into a mirror (rectangular sheet of reflective water) to check the fresh face gazing back, later rinse away yet another discarded persona in the shower; with Leah emerging from seawater (amniotic fluid) to be reborn.

You wonder at all the water, not just literal moisture but the translucent reflective surfaces revealing reflecting refracting Irene Becky Leah back at themselves and us — revealing reflecting refracting the mercurial creature men — and Guillen’s camera — pursue at their peril.

Her nights are punctuated by a recurring dream: Irene in a bathtub, humming (she’s always trying to cleanse herself); the shower curtains pull aside. “It’s over,” she says, smiling; Becky (and later Leah) wakes with a gasp. As the film progresses Irene stops delivering the line and the dream grows shorter and shorter, suggesting a life accelerating towards some yet unknown destination.

Guillen, a master of onscreen sensuality (see her breakout feature Salome) realizes the handsome production (design by Benjie de Guzman, art direction by Jerome Beley) with some of the most graceful camera movements (by Romy Vitug) and fluid editing (by Efren Jarlego) this side of Nagisha Oshima. Call this a prototype of what will soon be recognized as the glossy Viva melodrama, the glossiness an empty sheen if it wasn’t for Raquel Villavicencio’s finely crafted script.

The reigning genre nowadays is the romantic comedy and from the sheer volume churned out you’d expect our writers to have mastered the art of sexy banter, but no — today’s lovers sound barely educated, much less sophisticated. Villavicencio’s dialogue is in the tradition of Danny Zialcita and Ishmael Bernal’s musical-bedroom farces, with lines so finely honed they gleam like a knife display. “Are you married?” Leah asks when approached. “Is that still important?” asks the man. “Not to me,” Leah replies. “Not sure about your wife. I don’t want a scandal.” Step back to savor the stench of burning fuselage.

Perhaps Leah’s only real match is Jaime. “I’ve yet to see anyone happily married, have you?” she asks when Jaime proposes. “I might see more if people married for sex instead of love,” Jaime responds, “I know someone at work who likes to say ‘there’s more to sex than love.’” One may be reminded of Oscar Wilde’s fondness for flipped moral platitudes, and wonder why we don’t write dialogue like that anymore.

Call Guillen, Villavicencio, and Tolentino’s collaboration a masterclass in adult (as opposed to adolescent) entertainment, but there’s a dead-serious subtext: Irene Becky Leah conform and deform themselves according to the man’s wishes. “How many boyfriends have you had?” Armand asks; when he doesn’t like the answer, she knocks the number down to two. Jaime isn’t as naive but his jealousy is darker, his “games” more demanding. Of Mr. Eleazar we know little but we can be sure he had his own kinks, which Irene ably caters (“she makes hungry / Where she most satisfies”). Each persona costs time and effort to create and each must be washed away like so much congealed makeup before donning a new one. Some psychic baggage — that recurring dream for one — isn’t easy to abandon.

The thesis is a subtle one that feminists at the time struggled to accept. The kneejerk reaction was to glare at the protagonist and call her a slut; the more thoughtful response was to point her out as a negative example, ignoring the fact that she’s a victim despite her deceitful, manipulative ways (that because she’s been victimized she’s developed deceitful and manipulative ways).

In the film’s most meta scene, Leah bumps into Armand and they talk up in the stone bleachers of an empty stadium. “It’s like we’re in a movie!” Leah — Becky for the moment — observes. “Hasn’t that happened to you? Like you’re standing outside your body. I can do that. I can be outside watching my body. When something happens, I just watch. I wait till whatever’s happening ends.”

“And then?” Armand asks.

“Nothing. I leave.” What Becky — Leah — describes is not dissimilar to the mental state of a torture or rape victim attempting to survive her ordeal. Leah has likely attained that state at least once with Jaime; you wonder if she’s done so with Mr. Eleazar or (more to the point) with thoughtful caring Armand. When Armand tries to confront her, Leah — Becky — is evasive; Armand, however, won’t be denied. He bores in on Becky’s fabrications, tears them apart like so much tissue. Guillen often films Becky and Armand’s scenes in lengthy two-shots, to emphasize their intimacy; when Armand interrogates Becky the camera cuts from one to the other, emphasizing their disconnect. “I’m not your enemy,” he pleads, the camera following till she joins the frame. “I’m your husband.”

“I have to protect myself.”

“Yourself?” Armand and camera move away leaving Becky behind. “Yourself? What about me?”

Arguably the most painful episode: Armand forcing himself on Becky. Now that he knows what Jaime has done Armand attempts the same sadomasochistic games, earning Becky’s — and our — contempt. That sense of a woman rejecting a man recalls Anna Karenina’s rejection of Alexei; Guillen shoots handheld to underline the domesticity (there might be someone in the room recording the moment in videocam), in long takes to capture the depressing ugliness.

A point the filmmakers may not have intended: the film proposes that a woman should enjoy total freedom, even the freedom to be self-destructive. When Leah makes her latest decision, viewers may ask: “why?” She has chosen to be where she wants to be, if not when. And yes, in a bathtub — her recurring dream recurring one more time, with more water to wash away the consequences.

Final point: Leah may be a sub but it’s Jaime who pursues her. Jaime, despite all his declarations otherwise, is like Sir Stephen in Pauline Reage’s (a.k.a. Ann Desclos) The Story of O, he suffers a craving he cannot deny, he is conquered by Leah’s surrender. As with issues of feminism, freedom, memory, identity, and reality — on the question of who wields authority and who submits, Init sa Magdamag offers no easy answers.